You could say that the seed for the exhibition Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit at Pallant House Gallery was planted 20 years ago. Simon Martin, the director of the Chichester museum, was studying at the Courtauld Institute and doing work experience at Sotheby’s auction house when he first came across the artist’s sensitive portrait of a Black model called Félix from the 1930s. He went on to write his master’s thesis on Philpot (1884-1937), and since then, he says, he has been waiting for the “right moment” to put on an exhibition.

“Although we’re dealing with an artist’s work from 1900 to 1937, the themes that emerge are increasingly relevant today,” Martin says. The exhibition—the first major survey of Philpot’s work since his centenary show at the National Portrait Gallery in 1984—brings together several paintings, drawings and sculptures that have not been shown in public for decades, and focuses on his radical development from old-masterly portraits to a sparse Modernist style. “Based on reading his letters, I think he felt that he was no longer reflecting the world he was in and wanted to make the break,” Martin says. “He felt that he had become a kind of traditionalist.”

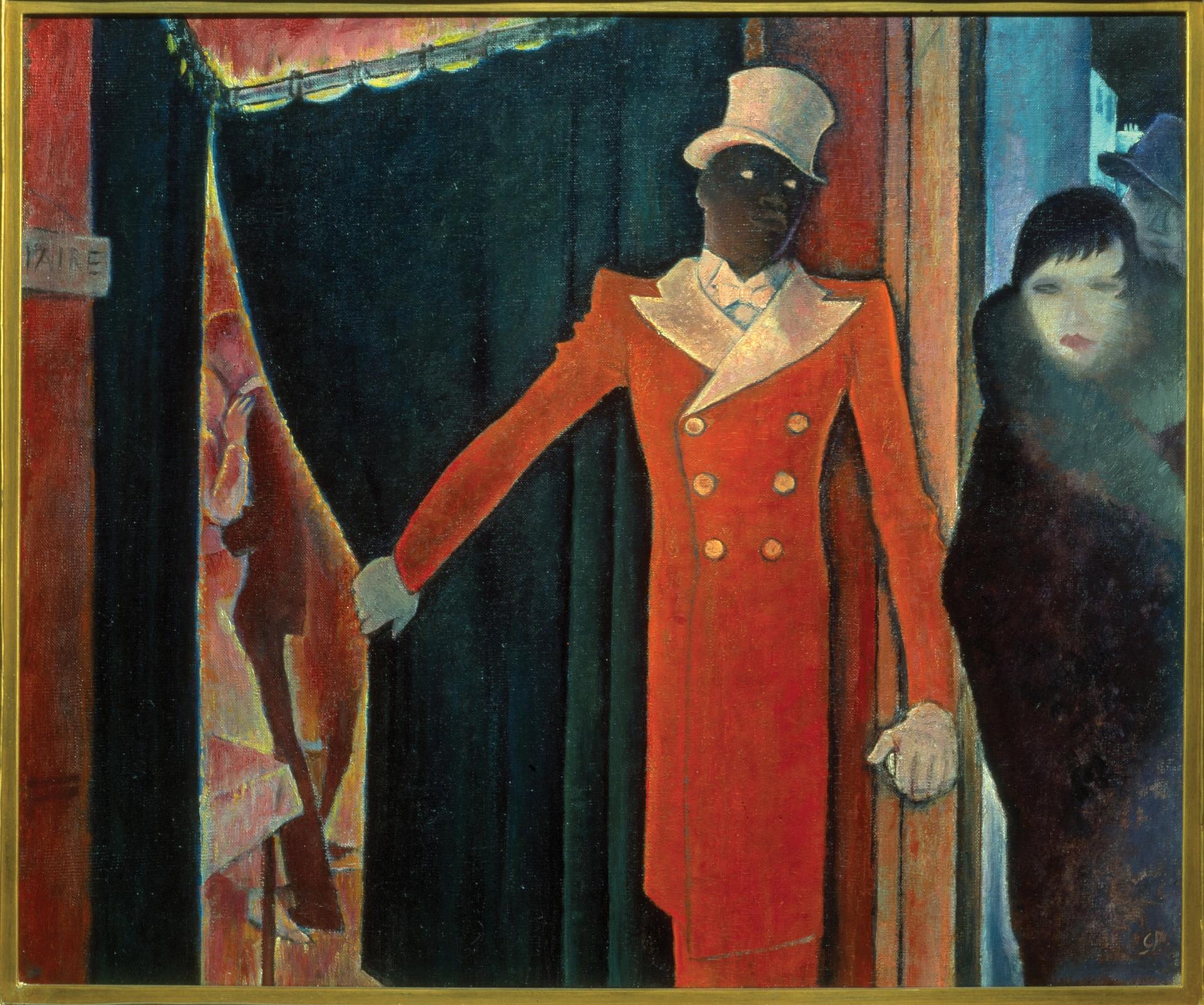

Philpot's Entrance to the Tagada (1931) Photo © The Fine Art Society, Bridgeman Images

There is nothing traditional about Philpot’s Black sitters, who, unlike those of some of his contemporaries, are presented with individual interest and respect. Martin has managed to source six portraits from 1912 to 1914, as well as a newly discovered portrait of Paul Robeson, the US actor and singer famed for his baritone voice. A key question has been how to address the often-anachronistic titles of unnamed models. Helping to answer it is an advisory group that includes Alayo Akinkugbe, the founder of the popular @ablackhistoryofart Instagram account, and the novelist Alan Hollinghurst, who has written the introduction to the exhibition catalogue. Following in the footsteps of Denise Murrell’s Posing Modernity exhibition and book of 2018, the name and nationality of each sitter will be added where possible.

Martin hopes to give an artist who deserves greater acknowledgement his due, and to change the way we think about Philpot, from a portrait painter to an individual expressing forward-thinking ideas about sexuality and race. “One of the extraordinary things is that he was so incredibly successful in the 1910s and 1920s, one of the highest paid artists in Britain, and then with the change of style everybody took a while to catch up,” Martin says. Today, with the renewed interest in the artist and his auction prices once again on the rise, it seems we have finally done so.

• Glyn Philpot: Flesh and Spirit, Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, 14 May-23 October