“I’m surprised it’s so good,” a friend was saying. He was talking about the television series that everyone has been talking about: The Andy Warhol Diaries, currently streaming on Netflix. Indeed, it is a surprise. Most attempts to portray artists in films sensationalise their subjects and often misconstrue their work. Andrew Rossi, whose catalogue as a director includes documentaries about the inner workings of The New York Times and the Met Gala, does nothing of the sort. While respecting the myth of the artist, he dives headlong into unexplored territory to articulate the truth of the man. And it hurts.

Here is an artist about whom we know everything, but also, by his design, next to nothing. The written diaries, edited by Warhol’s amanuensis Pat Hackett and published after his death in 1987, only told us what he wanted us to hear. (Who knew that Warhol wrote romantic poetry?) Rossi fills in the blanks by adding substantial historical context, particularly during the 1980s Aids crisis, and eliciting frank, remarkably self-effacing interviews from key figures in Warhol’s circle and informed observers as well.

Turns out that the character who called his tape recorder his “wife” and presumably hated to be touched, was carnal to the core. That will not come as news to Warhol’s closest confidants, but according to the candid testimonies they gave to Rossi’s persistent camera, even they were never sure if he consummated his desire.

Vincent Fremont. Photo: Patrick McMullan

“It’s very personal,” says Vincent Fremont of Rossi’s storytelling, lacing his approval with caveats that he shares with Bob Colacello, editor of Warhol’s Interview Magazine for a dozen years. “Humorless melodrama,” Colacello concluded in a rather grumpy review. “Andy was hilarious to be around, but you’d never know it from watching the sad sack depicted here.”

Only 20 years old when he started working at the Factory, Fremont became vice-president of Andy Warhol Enterprises—“a lifer,” as he puts it, “the one they trusted with the money.” He never thought he’d have to open Warhol’s last will. A catch in his voice, he added, “I never thought I’d be opening that last will.”

As a consultant on the six-episode Netflix series, Fremont opened doors for Rossi and his activist producer, Ryan Murphy (of the lurid Halston, also on Netflix), helping them to license a ton of forgotten footage and photographs that even Colacello concedes are revelatory and to secure the many poignant interviews.

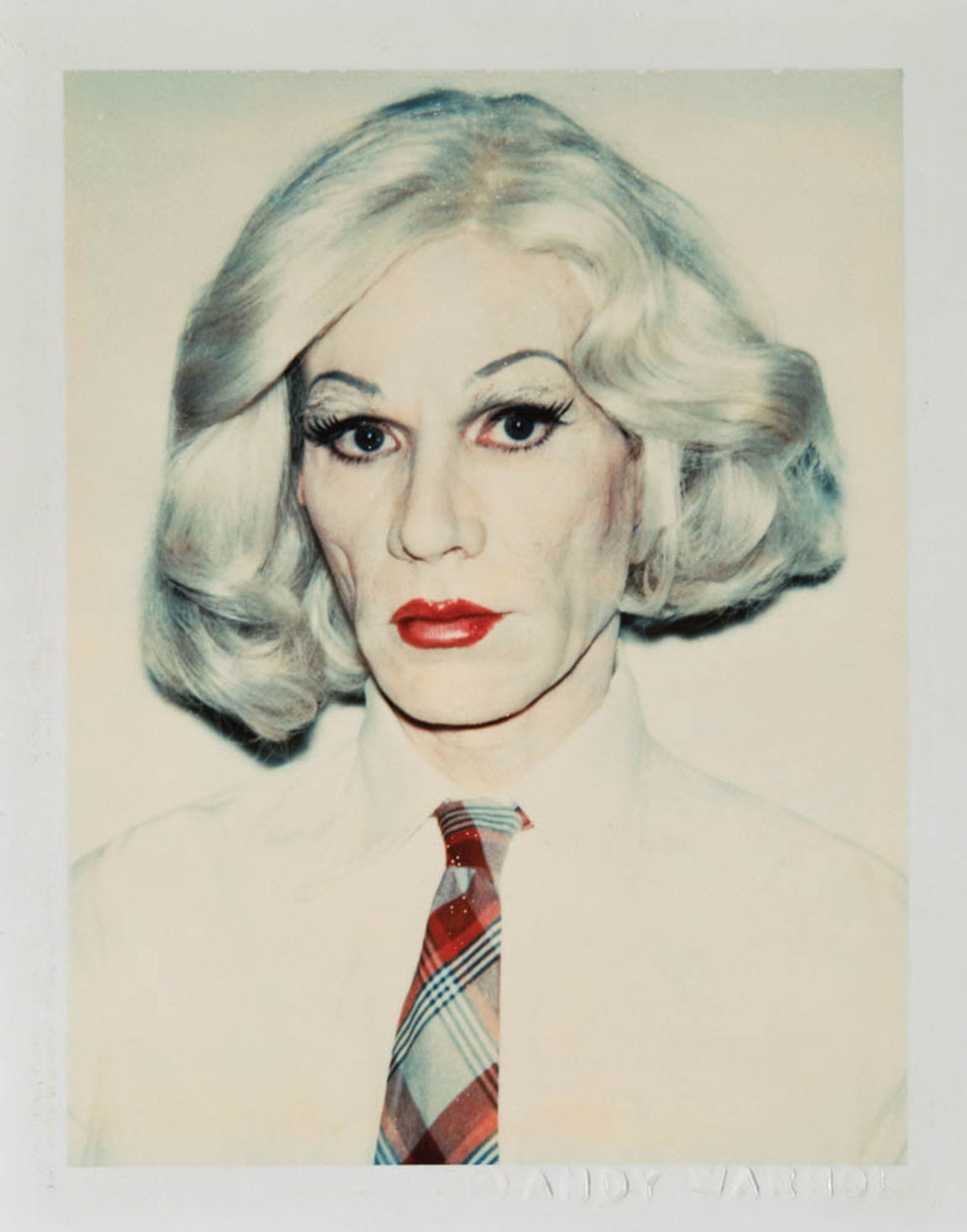

Andy Warhol photographed in drag by Christopher Makos.

Despite his objections, the series does allow us glimpses of the madcap Warhol: goading the squeamish Colacello into dressing in drag for a portrait, cracking wise in home movies captured by Fremont and the photographer Christopher Makos. (Weirdly, Warhol never looked more masculine than when he was being made up for Makos’s photographs of him in female drag.) Warhol’s presence at Ronald Reagan’s inauguration is another source of mirth, especially for Democrats like Donna de Salvo, curator of the 2019 traveling retrospective, Andy Warhol from A to B. “I loved it when Andy comments on how ugly the Republicans are,” she chuckles.

Nevertheless, Rossi’s tale, carried by brilliant editing, derives its considerable emotional power from the tragic.

“I found it incredibly moving,” says the writer Lynne Tillman, author of four essays on Warhol, including The Velvet Years, her book with the photographer Stephen Shore. “And it becomes richer and more profound as it goes on. For those of us who thought all along that Warhol had no soul, this is a corrective.”

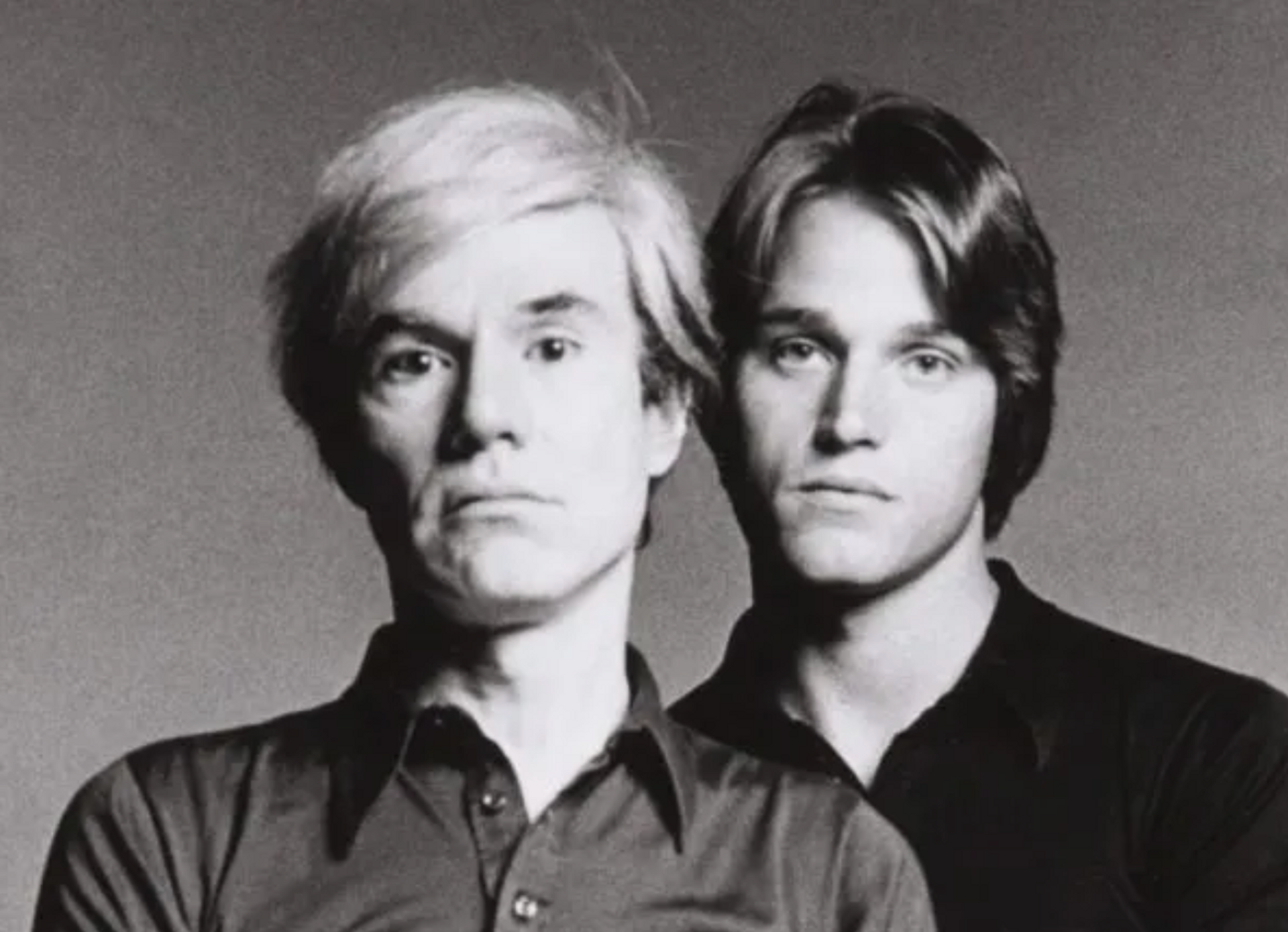

Jed Johnson and Andy Warhol, by Francesco Scavullo in 1981. Courtesy of Artnet auctions

The series hangs on the three most significant relationships in Warhol’s apparently tortured private life: his decade-long habitation with Jed Johnson, a former assistant twenty years his junior; Jon Gould, a semi-closeted Paramount Studios executive whom Warhol pursued, only to despair at his ambivalence; and Jean-Michel Basquiat, a mutual crush who would spurn his affections. Definitely, there is a lot of grief in what is actually a love story. All died too young.

In the first episode, the King of Pop is living with Johnson, initially his primary caregiver during his long recovery from the life-threatening wounds Warhol sustained in 1968, when Valerie Solanas shot him. The relationship turned sour over Johnson’s belief that the man he loved was wasting his talent by photographing the genitals of male porn stars brought in by Halston’s pal, Victor Hugo (“a horrible person,” according to Colacello). When Warhol went out at night, Johnson usually stayed home, growing so despondent that he attempted suicide. After a second try, Warhol reacted with a defensive cruelty, and Johnson found someone else. Still, according to Jay Johnson, Jed’s surviving twin, his brother remained in Warhol’s life, something not in the film. They had what Jay describes as “joint custody” of their two matching dogs, Amos and Archie, adopted when the lovers were living quietly in the town house that Johnson decorated on the way to becoming a sought-after interior designer.

Only its façade appears in the film. The many scenes supposedly shot inside the house were sets built to flesh out diary entries for which Rossi had no visual material. “The house was very family-like, nothing like what you see,” says Jay Johnson, who speaks with such honesty and compassion that his interview anchors the whole series with dignity. (Equally touching is Gould’s twin brother; strangely, his name is also Jay.)

“The filmmaker was gentle, and very well prepared,” Jay recalls, “but nobody really knew the house because hardly anyone was ever in it.” He frequently dropped by with his partner, Tom Cashin. “We went anytime we wanted. People didn’t know it, but Andy always had dinner at home before he went out for the evening, and we took advantage of that. Then he’d get up to go to a party and say, ‘I have to go to work.’”

The constructed scenes constitute the major misstep in Rossi’s opus. They irritate Colacello almost as much as the AI-assisted voice that recites the diary text as if Warhol had recorded them. “You get used to it,” Fremont says, and de Salvo agrees. “But,” she points out, “the nuances of Andy’s speech, his deadpan humor, are missing from the AI voice. It’s a monotone with a complete lack of affect. You only ever knew what Warhol meant by his tone. When you do hear his voice, it’s different. And you also see a facial expression. He created the mystery about him, the smartest thing he ever did. Even when he spoke the truth, people didn’t believe him. His position in history is firm, and I’m glad we have the work, but we’ll never figure him out.”

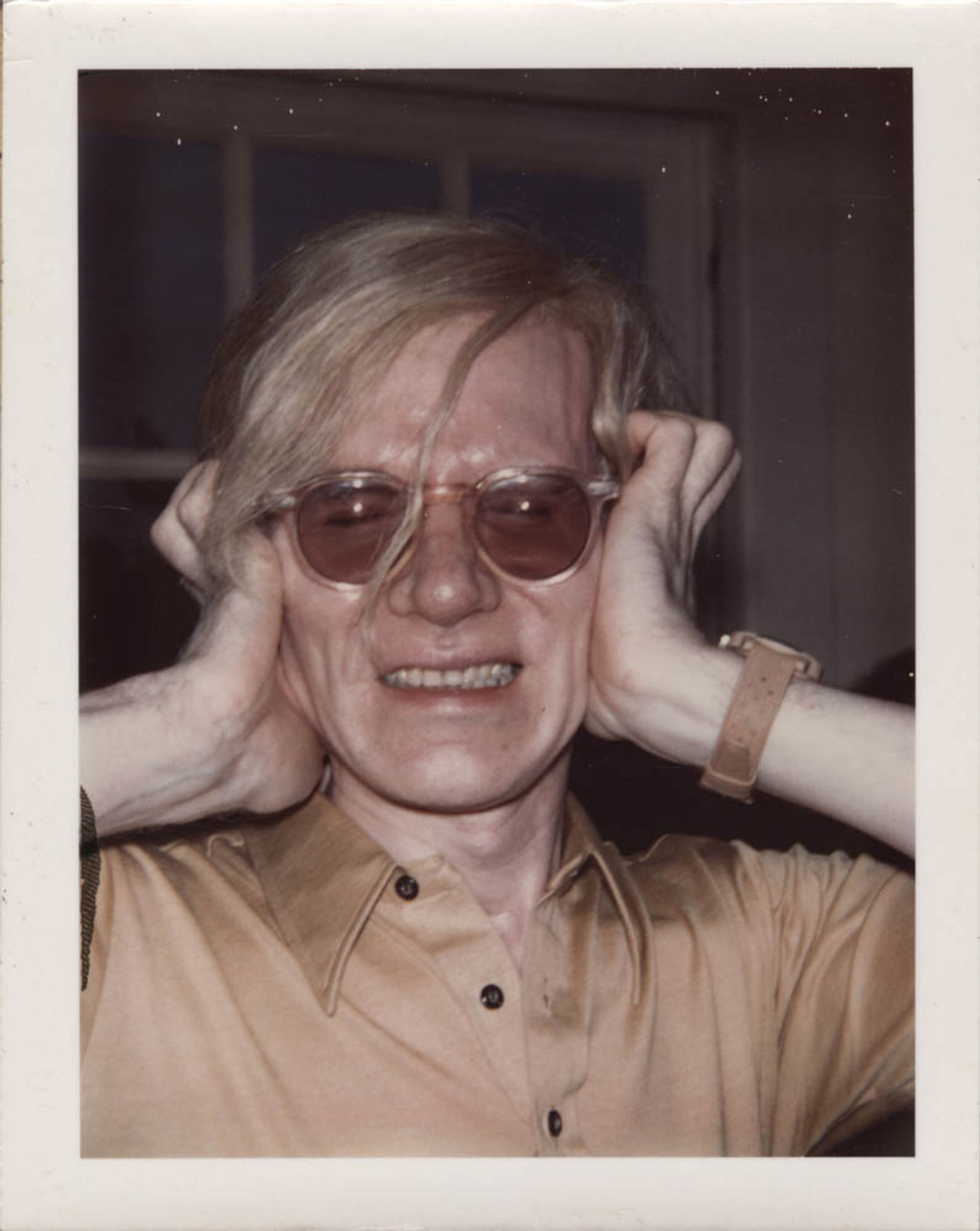

Andy Warhol in The Andy Warhol Diaries. Courtesy of Netflix © 2022. Photo: Andy Warhol Foundation/Netflix.

Yet, there have always been clues to the private Warhol. In his posthumously published memoir, the poet John Giorno, star of Warhol’s Sleep and an early boyfriend, is almost too explicit on the subject of their sex life. But that relationship happened well before 1976, when Warhol began dictating snippets of his social life to Hackett. It’s just that he skimped on details.

Which brings up another irritant for Colacello, who takes exception to the film’s implication that Factory staff conspired to keep Warhol’s sexuality secret. “That’s absolutely not true,” Colacello told me. “Andy just didn’t want to be pinned down.”

Warhol never pretended that he wasn’t homosexual. (Blowjob, anyone? My Hustler?) But he was so successful at keeping his private life hidden behind his public persona that even people who knew him well presumed that he was an asexual, if dirty-minded, voyeur.

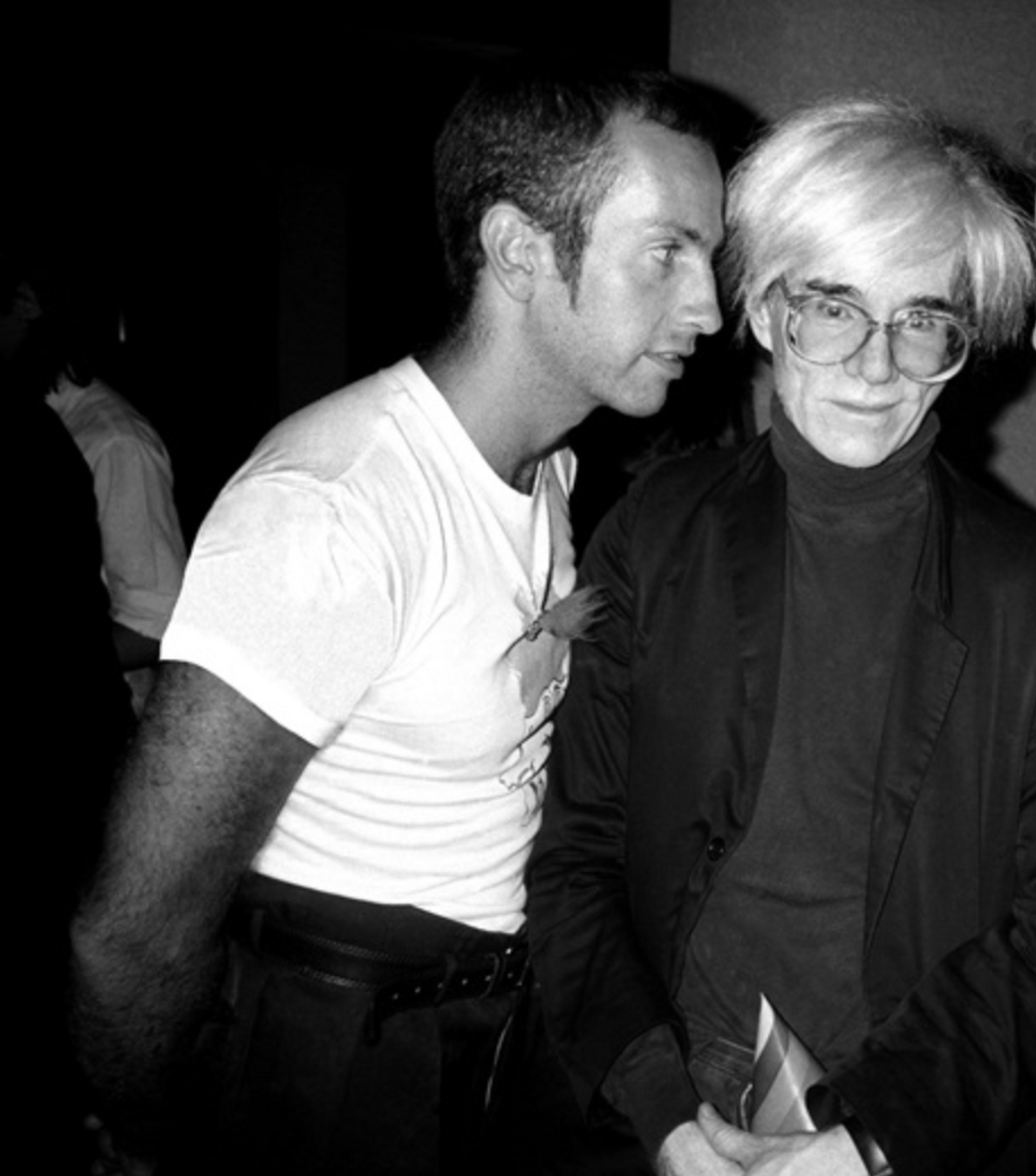

Kenny Scharf, left, with his mentor Andy Warhol at Elizabeth Saltzman’s birthday party at Il Cantinori on 16 June, 1986. Photo: Patrick McMullan/Getty Images

“A lot of things came up that I’ve never seen before,” says Kenny Scharf, one of Basquiat’s closest artist friends and a witness to the collaboration that returned Warhol to painting. “I didn’t know about Jed. And the Jon Gould stuff was just heartbreaking.” Memories of Basquiat are even more difficult. Their pain shows in Scharf’s body language on screen, though his reflections are not without cheer. “The GE logo that Andy used in one of his collaborations with Jean was my graffiti tag for a while,” Scharf told me. “Andy also used it in my portrait, and that made happy.” Basquiat, he adds, was not easy. Scharf tried, without success, to persuade his friend not to drop Warhol because of a demeaning review for their joint show in The New York Times. “I could relate to Paige Powell”—Interview’s advertising person and one of Basquiat’s girlfriends – “asking to go off camera when she cried.”

Upsetting though it is, Scharf found a lot to like in the series. For one thing, he says, “It wasn’t about the price of art. You have to listen to artists when they say something crazy, because they know stuff before anybody else.”