“Salary commensurate with experience.” This elusive phrase will feel all too familiar to many US museum and arts workers. But, in New York City and increasingly across the US, it will soon be a thing of the past.

From 15 May, employers in New York City will be guilty of “unlawful discriminatory practice” if they do not disclose a minimum and maximum salary or hourly wage on a job advert. The new ruling, an amendment to New York City Human Rights Law passed by the city council last December, applies to roles that are remote or in-person, permanent and short-term contracts, and to interns. Any company with more than four employees must adhere to it or risk civil penalties rising to $125,000 from the New York City Commission on Human Rights.

Proponents say the new law heralds a sea change in wage transparency that will help to ease the racial and gender pay inequalities that persist across industry sectors, including the arts. Tom Finkelpearl, the former commissioner of the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs, describes the new law as “good and important” for US museums and the American art world at large.

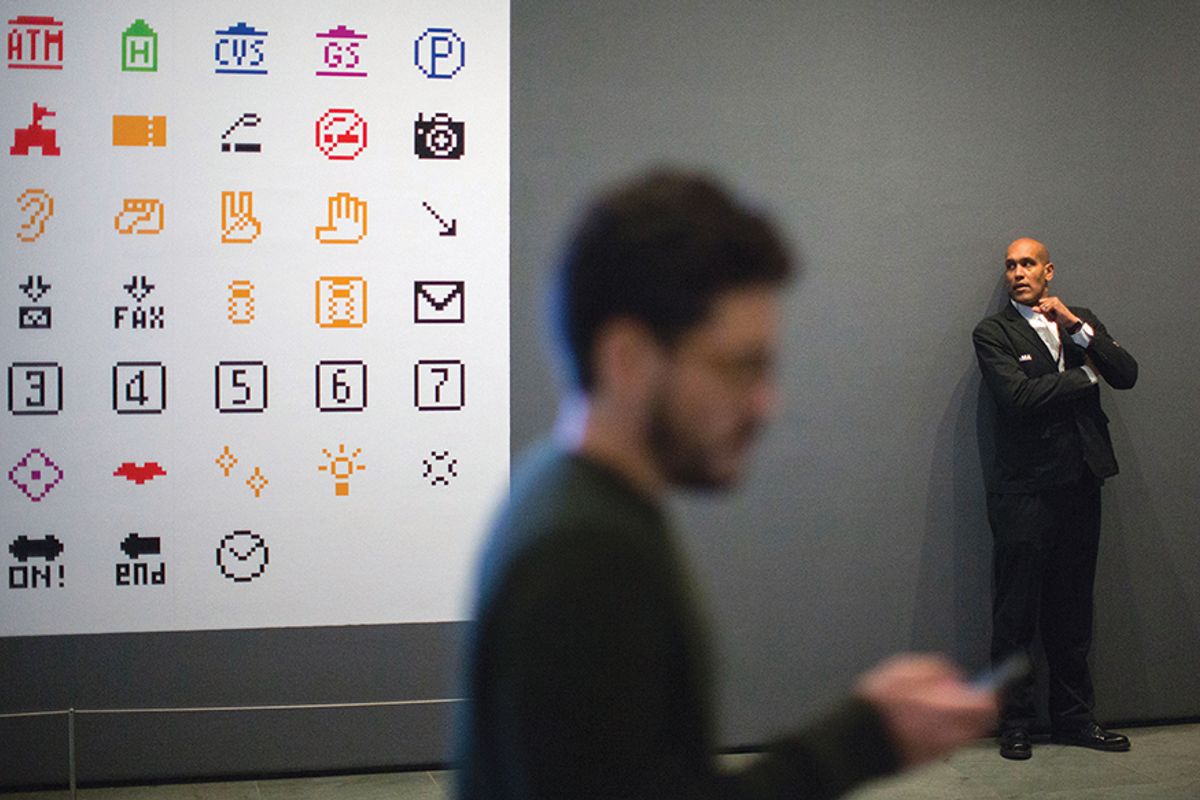

According to Indebted Cultural Workers, Glenn Lowry, director at MoMA, takes home around 48 times the salary of an education assistant at the museum Photo: Peter Ross

However, Maida Rosenstein, the president of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union’s Local 2110, which represents employees at New York museums including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Brooklyn Museum, warns that salary transparency alone will not “correct the situation”. She says: “Employers in museums won’t be able to obfuscate or hide about pay any more. But it’s only a start.”

“The US art world, including the museum sector, is notorious for being vague about salaries,” Finkelpearl says. “A job might pay $40,000; it might pay $80,000. Right now, you can’t necessarily tell, so you have to negotiate. But, after this law, they are going to have to be open with you from the start.”

This small shift, he says, could transform the hiring process, and potentially the wage structure, of some of the top cultural institutions in the US, many of which have been subject to activist campaigns and union pushes in recent years due to huge internal wage inequalities. MoMA’s director Glenn Lowry, for example, takes home around 48 times the salary of an education assistant at the museum, according to the activist group Indebted Cultural Workers. The museum’s tax filing for the fiscal year ending June 2020 listed Lowry’s reportable compensation from the organisation at more than $1.9m.

The US art world, including the museum sector, is notorious for being vague about salariesTom Finkelpearl, former commissioner of the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs

Finkelpearl describes New York City’s new law as being “long overdue” and sees it as part of a “generational shift around how people look at their jobs”. He points out that it comes in the wake of the so-called Great Resignation, or the Big Quit, which saw millions of workers across the country resign from their jobs during 2021.

Self-disclosure trend

The move also coincides with a new willingness among US museum employees to disclose their own salaries. Between 31 May and 31 December 2019, thousands of current and former employees of art institutions anonymously shared their salaries and conditions of employment via a viral Google spreadsheet, titled Art/Museum Salary Transparency 2019.

Wage transparency laws are a trend in the liberal states of the US. Seven states have now passed laws requiring employers to list salary ranges in job postings. The requirement already applies in Colorado, Nevada, Connecticut, California, Washington and Maryland, and will apply in Rhode Island from January 2023. Massachusetts and South Carolina look set to follow suit. But New York is the first major metropolitan city in the US to pass such a law.

In January 2020, New York state also made it illegal for employers to ask job applicants about their salary history. New York City had already prohibited this practice by law in October 2017. This, Finkelpearl says, is another game-changer. “We all know there’s inequity in terms of pay for women and people of colour,” he says. “Wage transparency helps stop that cycle.”