Until recently, the Renaissance and Baroque practice of painting on polished stone—from slate, marble, agate and alabaster to lapis lazuli and amethyst—drew relatively little attention from scholars. Most art historians tended to focus on the painted compositions themselves rather than the nature of the support used; some museums even incorrectly catalogued images as having been painted on wooden panels when the artist had left the stone exposed to exploit its distinctive colouring or striations.

Now, an exhibition at the Saint Louis Art Museum promises to illuminate this intriguing chapter in European visual culture, presenting around 75 works by 50 artists on 34 different types of stones from the 16th and 17th centuries. The product of 15 years of research, Paintings on Stone and its rich catalogue also delve into the resonance of stone in mythology and Christian doctrine; the notion of painters collaborating with God or nature, the ultimate artist; and the expansion of traffic in stone from far-flung quarries.

“Was it a painting, or an objet d’art?”

The idea for the show was seeded in 2000, when an enthusiastic patron underwrote the museum’s purchase of Giuseppe Cesari’s Perseus Rescuing Andromeda (1593-94), a tiny but virtuosic rendering of the mythological tale painted on lapis lazuli. Learning that the painting was to be auctioned at Christie’s, Judith Mann, the museum’s curator of European art to 1800, dashed to New York to view it and was dazzled by how the lapis was harnessed for the colouration of the blue sky and blue-green sea. “It was neither fish nor fowl,” she recalled in an interview. “Was it a painting, or an objet d’art?”

The more Mann learned about the work, the more curious she became about how common the practice of painting on stone was for European artists in the 16th and 17th centuries. With the help of other researchers, she began amassing a database that today encompasses around 1,400 images—no doubt a tiny fraction, she notes, of what was created in Rome, Medici Florence, Venice, Madrid and Antwerp, as well as Rudolf II’s court in Prague and other artistic centres. By 2005 she had resolved to organise an exhibition about the phenomenon, an idea that she eventually refined to focus on the most evocative paintings as well as cabinets of curiosities inlaid with miniature examples.

Filippo Napoletano's Sea with Galleons (around 1617-21) Opificio delle Pietre Dure; National Institute of Etruscan and Italic Studies of Florence

Though common in antiquity, the practice of painting on stone appears to have largely receded until the 1530s, when artists began experimenting with the process in the competitive cauldron that was Rome. Crucial to its introduction was the Venetian-born Sebastiano del Piombo, who developed a formula for ensuring that the oil paint would adhere to slate. “In terms of flaking, Sebastiano’s pictures are in very good condition today,” Mann notes. (An insouciant innovator, the artist would enrage Michelangelo by prepping a Sistine Chapel wall for The Last Judgment (1536-41) with a smooth surface for oil painting rather than the rough texture required for the fresco technique.) Though the paint completely covered the stone in these 1530s works, the rock’s presence nonetheless accrued meaning by invoking Christ’s role as the cornerstone of the church and his resurrection from a stone tomb sealed by a boulder.

By the 1590s, when more interesting stones had become available, artists were incorporating the hues of the material and its natural markings—swirls, concentric circles, meandering lines—into their compositions. In addition to flaunting the blues of the Afghan lapis lazuli in his Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, Cesari, also known as Cavaliere d’Arpino, painted Andromeda’s feet to align with a prominent crack in the stone, and the edge of the rocky cliff corresponds to a greater presence of calcite in that section.

The work also delights in an array of stone metaphors. Andromeda is tied to a rock when Perseus swoops in to rescue her from a sea monster: she is so beautiful that the Greek hero initially thinks she is an exquisite marble statue. “And of course he’s running around with the head of the Medusa,” whom he had decapitated earlier, Mann notes, “and gazing at Medusa’s head turns people to stone. There was lots of opportunity here for intellectual play that would have been appreciated by erudite circles in Rome.”

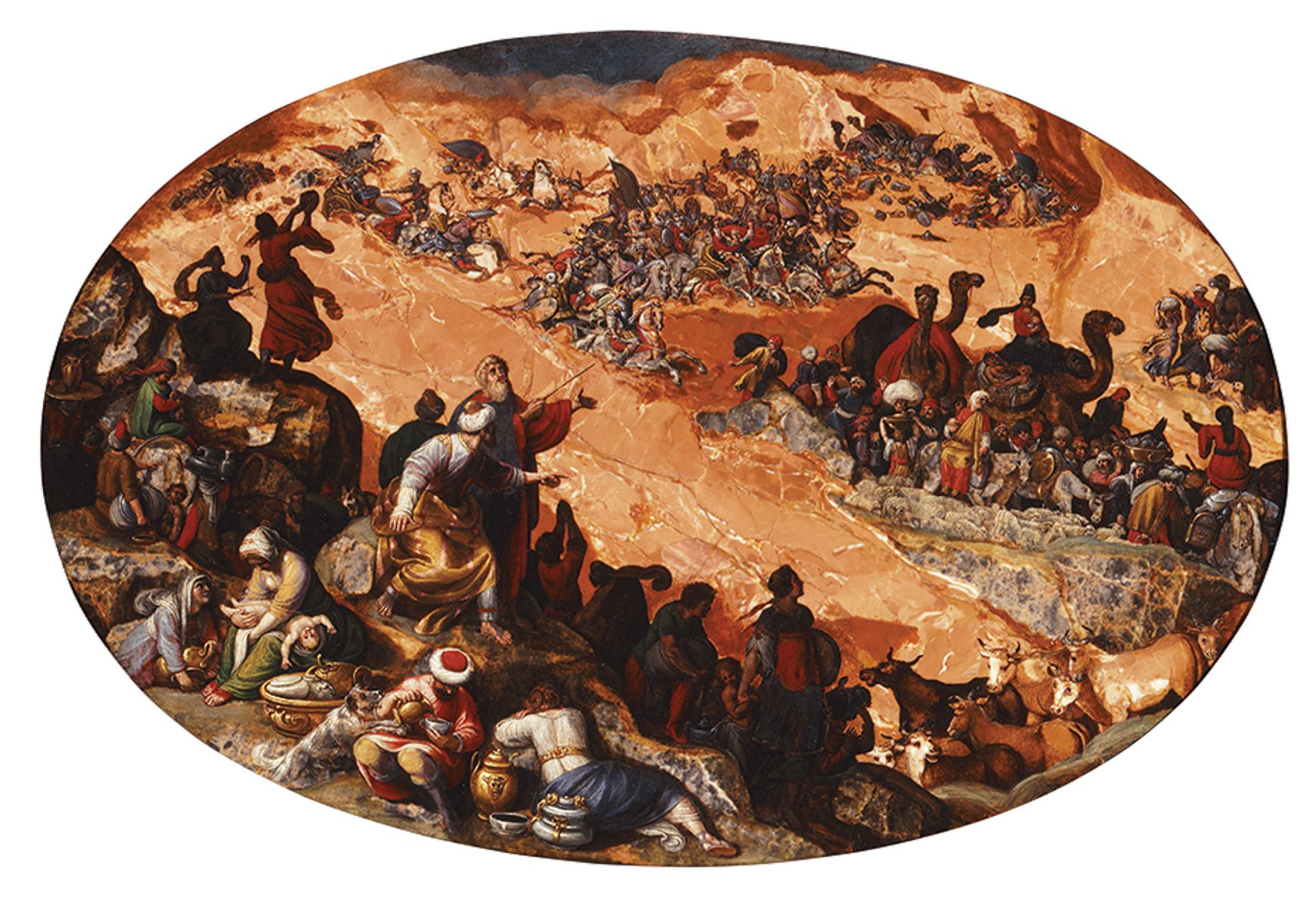

The brecciated limestone of Antonio Tempesta’s Crossing of the Red Sea (1610s) conveys the water’s movement Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

There are many examples of artists cleverly incorporating the underlying stone in their compositions. Orazio Gentileschi applied glazes to the alabaster in Annunciation (1602-05) to render fluffy clouds and weaved its natural markings into the background columns and Mary’s prayer kneeler. Antonio Tempesta’s The Crossing of the Red Sea (around 1610) uses the mottling of the salmon-coloured limestone to suggest the flow and current of the waters, wielding paint so subtly that it is hard to see where the natural stone begins and ends.

Why the fascination with the topic, after long scholarly indifference? Mann suggests that the proliferation of art images on the internet, with their two-dimensional flatness, has paradoxically sowed a greater appreciation of materiality. “People know that these objects are anything but flat,” she says. “They’re interested in their quality as things.”

• Paintings on Stone: Science and the Sacred 1530-1800, Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, 20 February-15 May