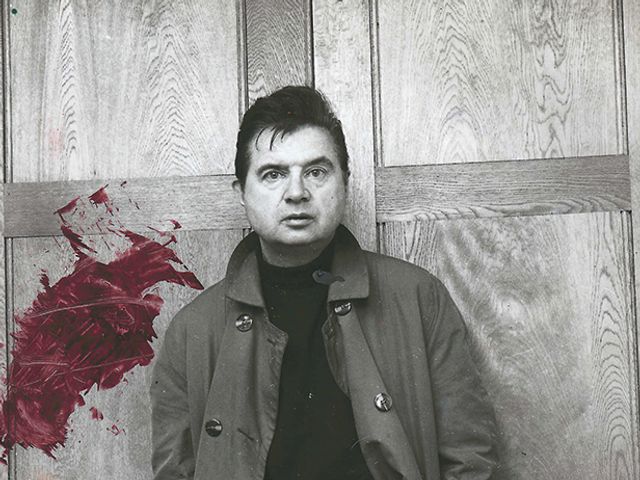

Not many people can claim—publicly at least—to have been photographed naked in the bath by Francis Bacon. James Birch was a small child when he was innocently snapped in the tub by the painter buddy of his family friends Dicky Chopping and Denis Wirth Miller, an artist couple who lived near his parent’s holiday cottage on the UK’s east coast. The nihilistic maker of the shrieking, bleakly existential canvases currently on show at the Royal Academy’s survey Francis Bacon Man and Beast seems a far cry from Birch’s more benign memories of the genial avuncular figure who was a regular fixture throughout his 1960s childhood, writing him letters addressed to "Rawhide" after the TV series with which the young Birch was obsessed.

James in Bath by Francis Bacon Courtesy of James Birch

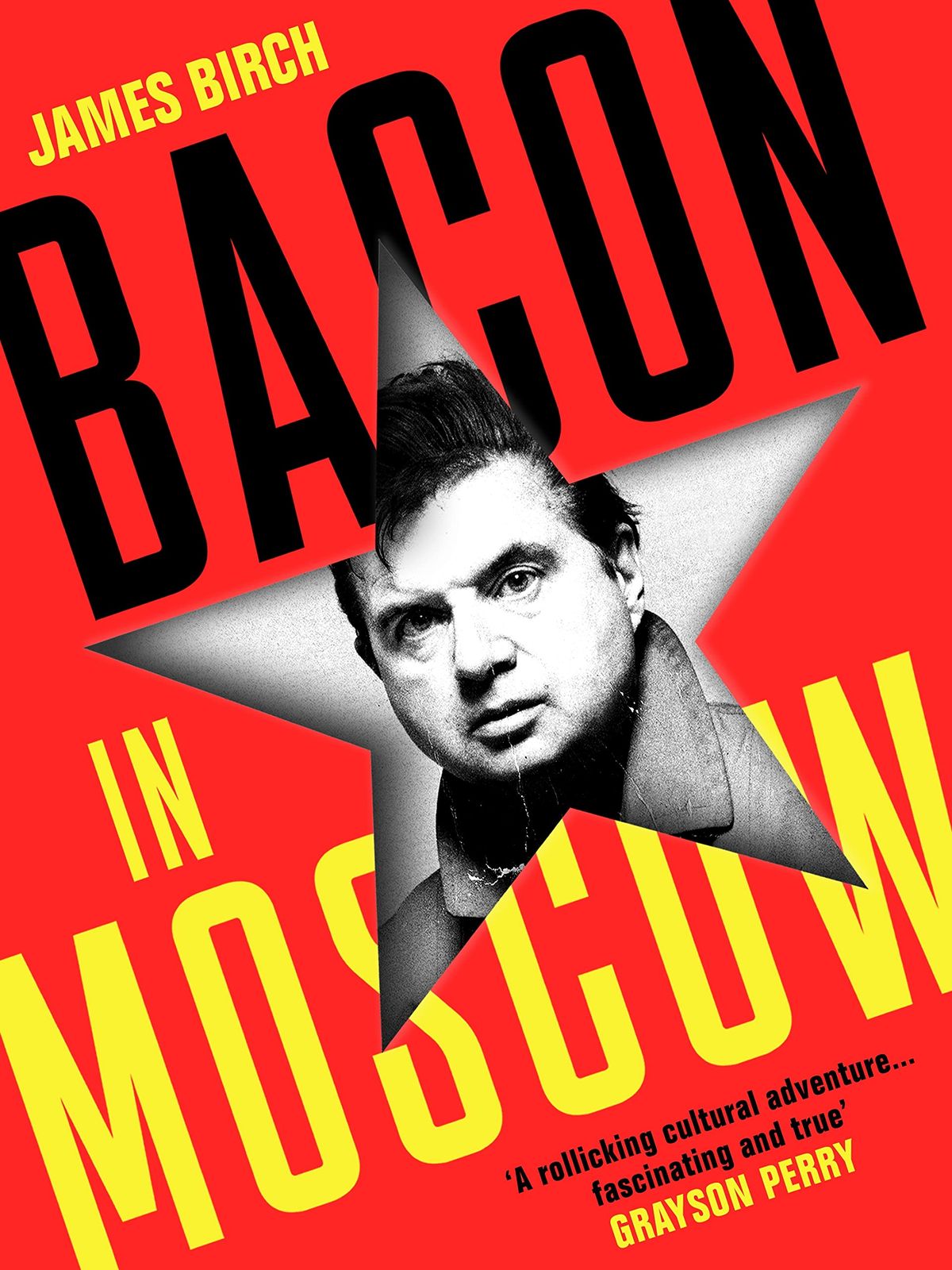

The bathtime shot and a fond "Rawhide" message scrawled in Bacon’s unmistakable loopy handwriting form the opening salvo to Birch’s memoir Bacon in Moscow (Cheerio, 2022). The book centres around how, a couple of decades later in 1988 and now an aspiring art dealer, Birch managed to organise a major Francis Bacon retrospective at the Central House of Artists in Moscow—the first show of a living western artist in Russia for over half a century. (Birch had initially wanted to bring his new protégés Grayson Perry and the Neo Naturists, but that was a step too far for the Russians.)

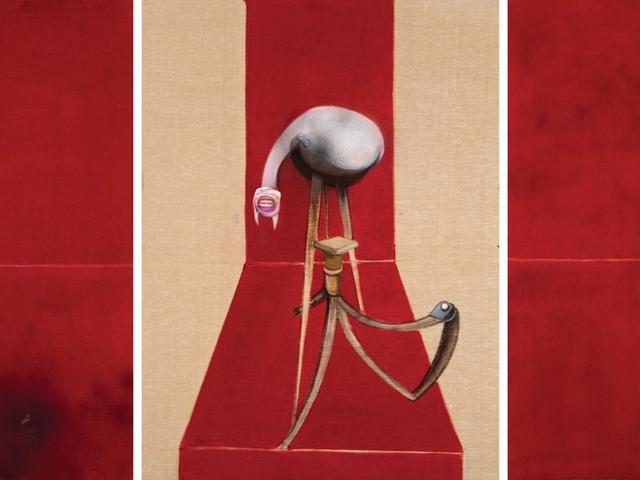

Bacon’s Moscow show may now be a footnote in mainstream art history but in Moscow it was a landmark event, attracting over 400,000 visitors during its six week run between 22 September-6 November 1988. The tumultuous account of how Birch pulled off this audacious feat (and how others stepped in to use it for their own agendas) is a gripping, rollicking read, rife with shady characters and sinister machinations from the powers that be in Russia as well as within the London art world.

Bacon and beasts: an in-depth look at the visceral new show at London’s Royal Academy of Arts

There’s Sergei Klokov, the mysterious KGB officer with an interest in culture, clad in Pierre Cardin and with a penchant for male handbags (but whose weapon of choice whilst serving with the Russian army in Afghanistan was a flamethrower); and Klokov’s companion and “muse”, the impossibly beautiful fashion designer Elena Khudiakova, who subsequently ended up co-habiting with Birch in London whilst all the time still filing secret reports to her Soviet masters.

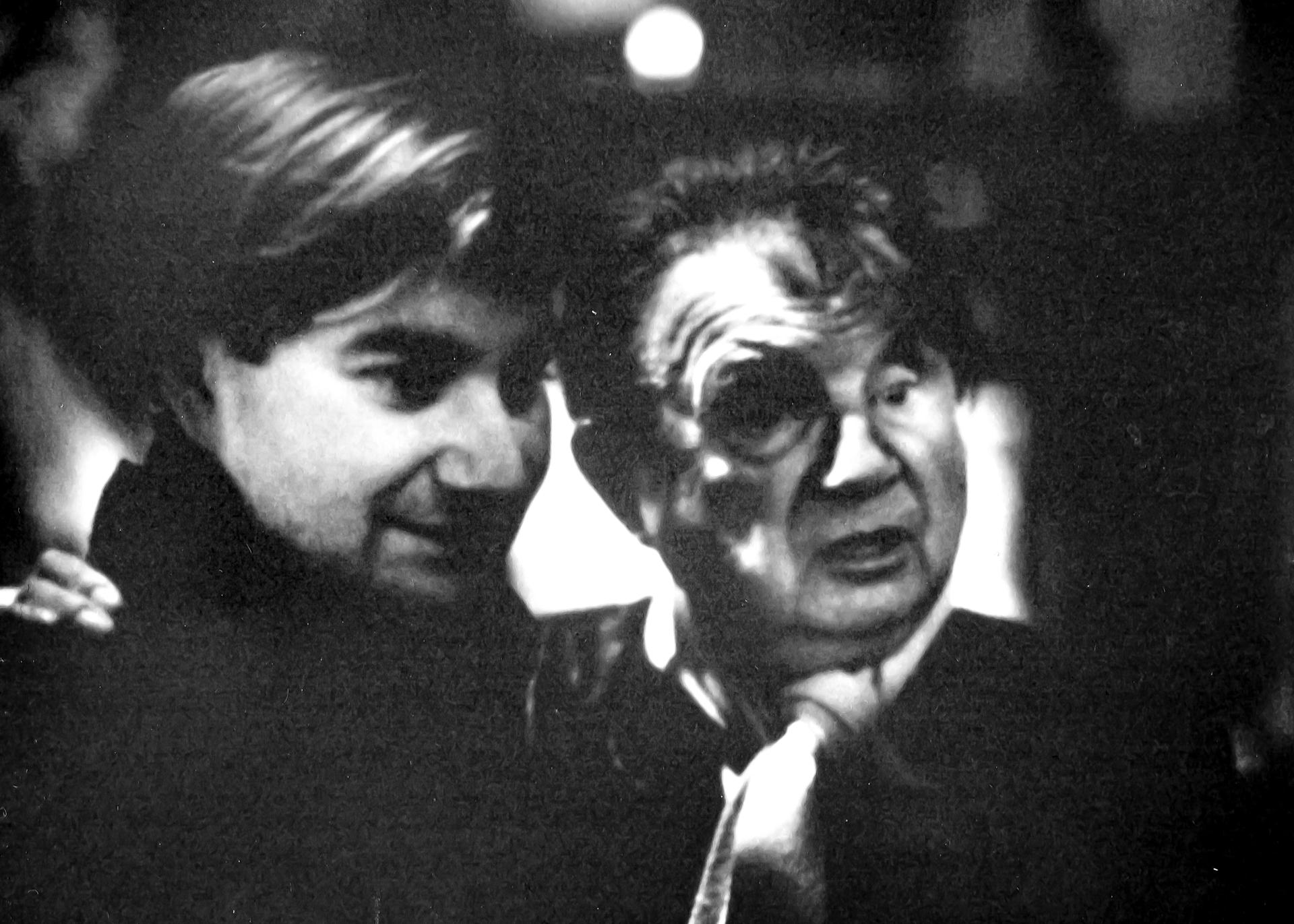

Francis Bacon and James Birch Photo courtesy of James Birch

The London protagonists include Lord "Grey" Gowrie, Margaret Thatcher’s former arts minister, who wrote Bacon’s catalogue essay but at that point was also the director of Sotheby’s, which was poised to hold the company’s first (and highly lucrative) art auction in Moscow; and Henry Merrick Hughes, then-director of the British Council, who originally offered to pay for Bacon’s Russian debut but then reneged. The tab was eventually picked up by the Marlborough Gallery, but not before they had attempted to deduct the costs from Bacon’s personal account. Also lurking in the wings was the disgruntled art critic David Sylvester who, Birch believes in a fit of pique at not being asked to contribute to the catalogue, was instrumental in discouraging Bacon from attending the show by fuelling the frail 79-year old’s anxiety about the effect of such a trip on his health.

So Bacon pulled out of going to Russia at the last minute and never got to see his 30 paintings hung in Moscow. Instead he sent his friend John Edwards, who featured in several of the works on show, as his representative. (Bacon gave Birch £3,000 to cover Edwards’s expenses, although condoms apparently proved to be a better currency for purchasing caviar in late-era Soviet Russia).

Louisa Buck and James Birch at his book launch Photo courtesy of Louisa Buck

Bacon in Moscow might be the ostensible subject of this book, but what emerges from this picaresque saga of an exhibition realised amidst spats, feuds, promises broken and much drinking and dining on both sides of the Iron Curtain, is that Birch and Bacon were just part of a much bigger game being played out between the West and Moscow. As well as offering a vivid account of a now largely forgotten cultural event, in the sharply observed details and telling anecdotes that emerge out of Birch’s long relationship with this most contradictory, perverse and much-mythologised artist, Bacon in Moscow brings Francis Bacon and his motley milieu to life in ways that even the most meticulously researched and scholarly biographies never can.

Bacon in Moscow is the first publication to emanate from Cheerio, the imprint and production company launched in 2020 in collaboration with the Bacon estate and named after the artist’s favourite drinking toast. There were certainly many Cheerios at the book’s Moscow-mule-fuelled launch last week at Hatchards in Piccadilly, where the throng ranged from fashion designer Zandra Rhodes to artist Jeremy Deller as well as Grayson Perry and Neo Naturist Wilma Johnson, both of whom seemed to have forgiven Birch for their being passed over in favour of Francis Bacon all those years ago.