If you could live with just one work of art, what would it be?

One thing that I did when I was a graduate student was make my own Robert Motherwell paintings. I love the Elegies to the Spanish Republic [1948-67]. I could never afford one, so I just decided to make them. Those paintings are in my home and they’re ones that I’m sort of incredibly embarrassed by but, as the years go by, really proud to have.

Which cultural experience changed the way you see the world?

When I was about 12 years old, my mother found something called the Centre for US/USSR Initiatives [now the Centre for Citizen Initiatives]. And that landed me in the forest of what was then called the Soviet Union. So I studied art in the forests of Russia, with young Russian kids, under the auspices of the CIA.

It was the most bizarre programme, part of one of those sort of ping-pong political things where you hope that American kids will influence Soviet kids, and then the following year the Soviet kids come to America. But in the wash, what happened was that my brain exploded. My sense of the possible went far beyond South Central Los Angeles, a very underserved community at the time. And it gave me a sense of ownership and a sense of inheriting the fullness of not just one place, or one set of practices; it felt as though the entire history of art were something that I was heir to.

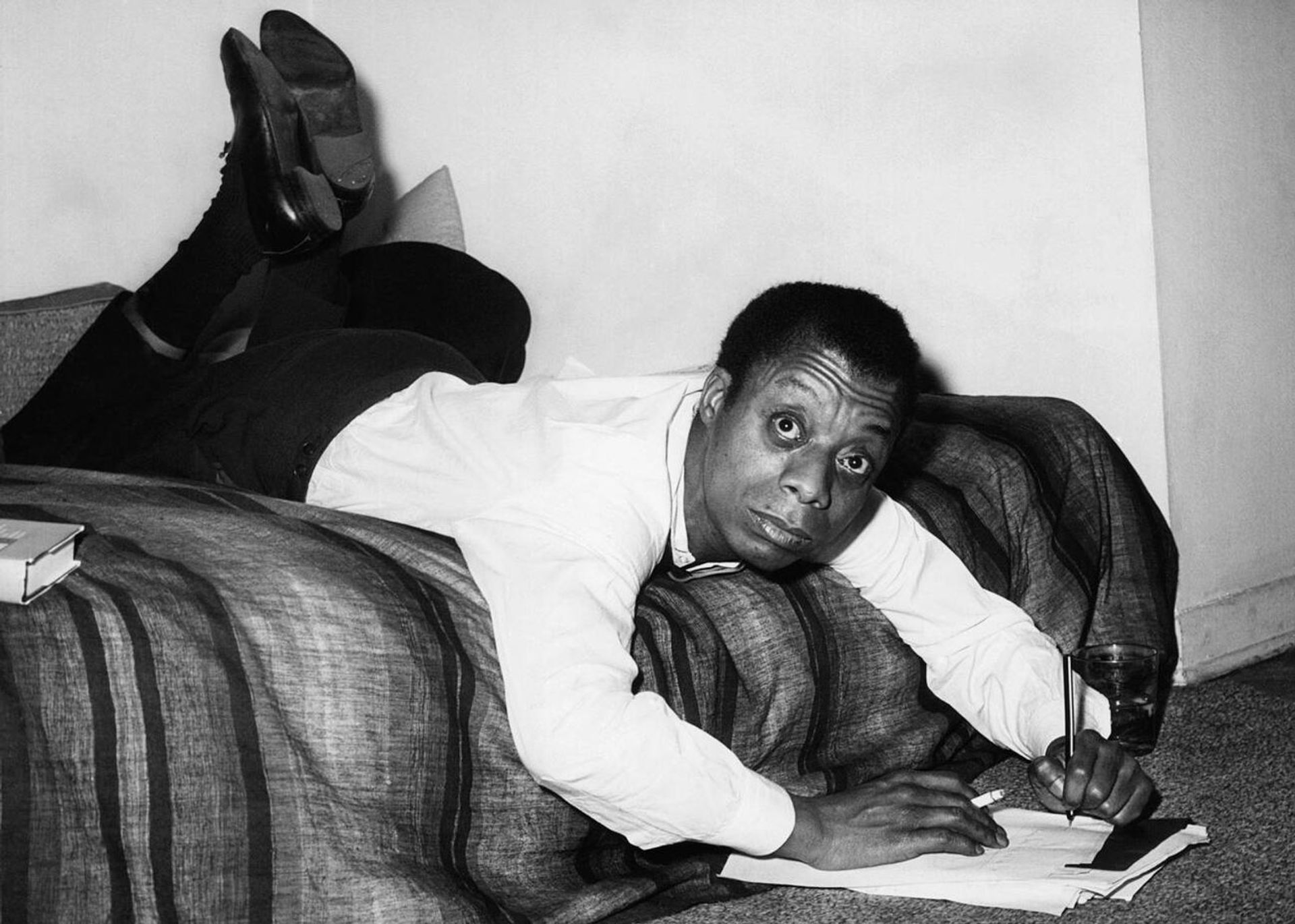

The work of James Baldwin (above) resonated powerfully with a young Kehinde Wiley. © Alamy

Which writers or poets do you return to the most?

James Baldwin is one of those voices that is so authentic, and so familiar, and so blazingly brilliant that it resonates in a way that is both creative and poetic, but also sets alight one’s mind politically. He also gets into topics surrounding human sexuality as it interfaces with race in a way that was very exciting to me as a child.

I remember discovering Richard Dyer when I was a kid, and he was engaged in something called “whiteness studies”, which back then was a feature of the developing practice of critical race theory. Whiteness studies exist in exact relationship to Native American studies, African American studies, Asian studies. So the idea is that if whiteness is something that is anywhere and nowhere and ineffable, but somehow influencing every aspect of design culture, architecture, politics, science, why is it so hard to pin down?

Ultimately, we arrive at the ridiculous nature of all of these defining categories: the invention of race, the invention of nationhood; all of them become useless as tools. At a certain point, at a certain altitude, we all become the same. And Dyer is able to look at the rhetorical history of painting, follow it through the material practice of filmmaking, follow it through Pop culture and queer studies, and really bring it alive—less theoretical and something that’s more consequential and actual.

What music or other audio do you listen to while you’re working?

Now, I’ve got the soundtrack of The Prelude [Wiley’s film at the National Gallery] in my mind. It’s an incredible score created by a young composer named Niles Luther. I am obsessed with this music and, hopefully, we’ll work on other projects in the future.

What is art for?

Art is for us to deal with the existential fact of extinction. It’s for us to be able to dance in the face of doom and to be able to create something that lives underneath the inevitable fact of our death.

• Kehinde Wiley, The Prelude, National Gallery, London, until 18 April 2022; The Obama Portraits Tour is at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until 2 Jan 2022. He features in 30 Americans, Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina, until 17 January 2022. And his work is in Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear, at Victoria and Albert museum, London, from 19 March 2022.