When Johnny Bandura was first inspired to paint a mural comprised of portraits of the 215 children whose remains were found on the grounds of the Kamloops Residential School last May—a tragic revelation that prompted a national reckoning with Canada’s colonial legacy—he never imagined the journey his work would spark. The striking, Comix-inspired images of the children imagined as they might have looked had they survived to adulthood, have touched viewers around British Columbia at a variety of exhibitions, serving both as a memorial and as an educational tool.

“Since the first National day of Truth and Reconciliation on Sep 30, 2021, where the project was first shown to thousands at the Kamloops ceremony,” Bandura says, “there has been a huge demand to show this work, especially from Canadian educators.”

The graphic yet painterly portraits of “what these children could have become” sprang forth spontaneously from Bandura’s Edmonton studio in what he describes as a therapeutic process, and a way of processing trauma to which he had a very personal connection as the grandson and brother of former students at the Kamloops school. The portraits, all set against a yellow backdrop with features etched in black and white, punctuated by vivid reds and greens, include a medicine woman, a hunter, a nurse, a hockey player and a judge, with some wearing traditional regalia. They all share the same open, questioning eyes that demand viewers return their gaze.

And as more revelations of mass graves continue to rock the nation, the portraits seem to elicit especially heartfelt responses from young viewers. As news of Bandura’s mural spread, largely through word of mouth and social media, he was approached by curators at the Anvil Centre community gallery in New Westminster, British Columbia. This was a natural home for the mural as Bandura is a member of the Qayqayt First Nation (New Westminster is on their unceded territory) and is the nephew of Qayqayt Chief Rhonda Larrabee.

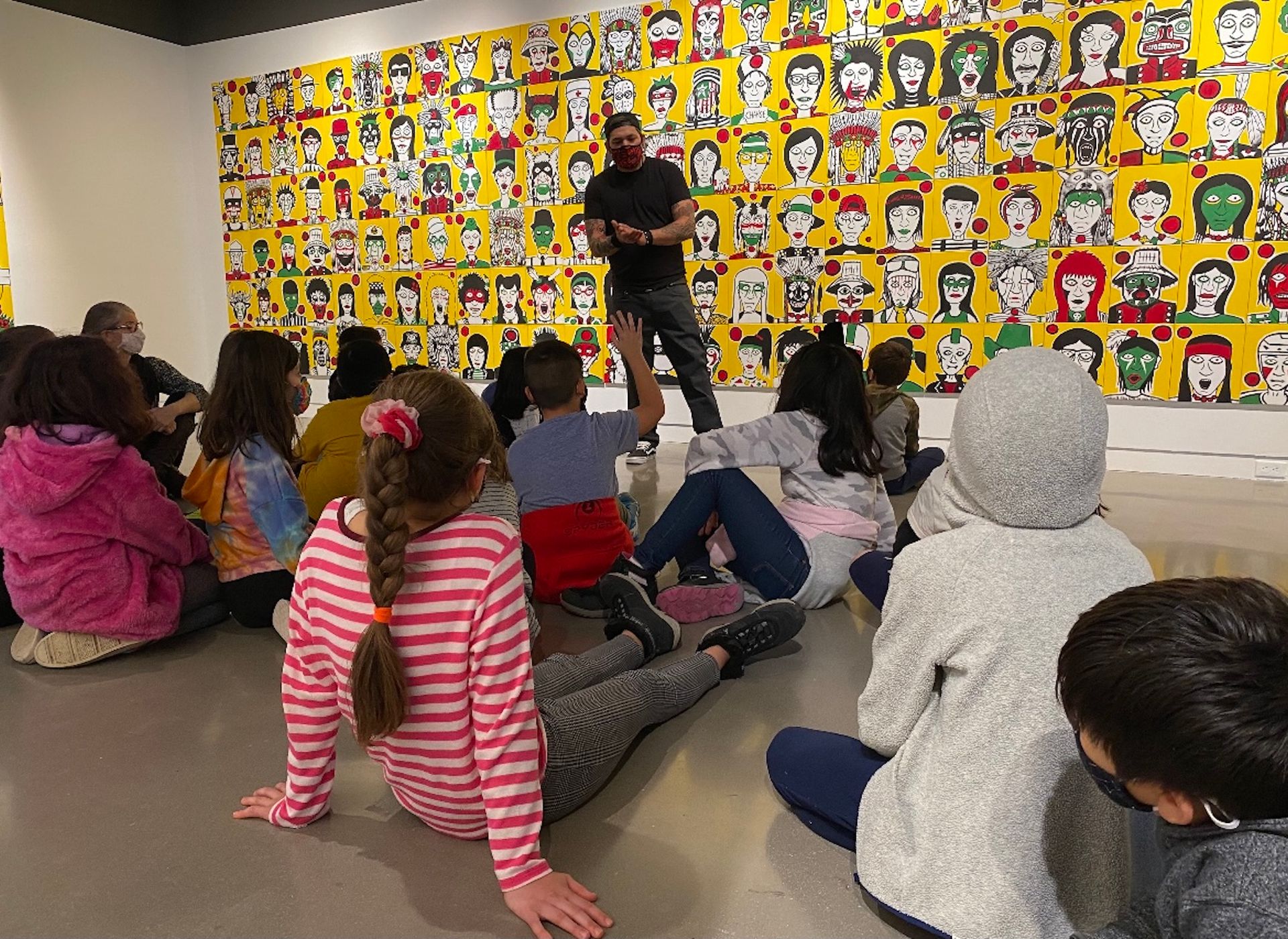

Working with curator Rebecca Salas, Bandura developed a programme to give viewers tours—booked in advance due to Covid-19 restrictions—through the exhibition and answer their questions about residential schools and his own work as an artist.

“Through Johnny’s portraits, children are able to follow their natural curiosity and ask questions about what they see—whether it is something familiar, something unfamiliar, or even the colours Johnny used,” Salas says, “there are so many ways students of all ages are able to engage with the topic.”

Artist Johnny Bandura discusses his portrait series with students Courtesy the artist

The two-week exhibition, Bandura says, was fully booked and, in addition to the mayor and city council of New Westminster, attracted hundreds of high school and elementary school children and their teachers. He adds that educators “are using the paintings as a tool to teach children about colonization and the residential school system and the things that happened there”.

Now images of Bandura’s mural and a short summary he wrote about his own background and creative process will be featured in the Knowledge Makers Journal, published by Thompson Rivers University (TRU) in Kamloops, as part of an undergraduate indigenous research program that, in its pandemic-era online iteration, also includes students from New Zealand and Australia.

“Because TRU is on the unceded and occupied territories of Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc where the 215 children were found,” says Sandra Bandura, associate director of All My Relations Research Centre, which runs the Knowledge Makers Program, and Johnny’s older sister, “we knew that we had to save space for them in the journal.”

In tandem with the publication of Bandura’s work in the journal, an on-campus exhibition of the mural will open later this month. After journeying back to Kamloops, the portraits will travel to Victoria, British Columbia, the provincial capital, where they will be displayed in the Parliament building. Bandura hopes “they can again be seen by elementary and high school students to learn about the residential school system and the role that the government had to play”.

The artist is now at work on his own, self-published monograph documenting the portraits.

As for his own educational experience as a young student, Bandura says, “I don’t remember being ‘taught’ anything about Indigenous people other than stereotypes about us being ‘makers of baskets and canoes.’”

Now his artwork acts as a potent counter-narrative to outdated curricula and a powerful device for the education of a new generation.

“I always felt that the education system viewed art as a secondary subject in school—not a subject to be taken seriously,” he says. “But it was the only one I did well in, so I’m happy that my art is making waves.”