Haroon Mirza works with sound, light and electricity to create kinetic sculptures, performances and immersive installations. These draw on myriad influences—scientific, historical, cultural—and respond to them with equivalent diversity. He won the Silver Lion for most promising young artist at the 2011 Venice Biennale with The National Apavilion of Then and Now, a triangular anechoic chamber (a space with no echo) lined with sound-absorbing foam and fitted with LEDs that generated a noise which intensified as their light brightened. It is now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In response to a 2018 residency at CERN in Switzerland, the London-based artist co-produced a film and an opera incorporating music, poetry, incantation, archive and homemade electronic instruments, some built from discarded CERN laboratory equipment; in the same year his solar-powered Stone Circle, nine marble boulders fitted with speakers and LEDs, was permanently installed in the Texas desert following a commission from Ballroom Marfa. In For A Dyson Sphere, his second solo show at Lisson Gallery, New York, Mirza explores the technological pursuit of energy, a theme that will extend into a new commissioned work for lille3000 in March.

The Art Newspaper: Can you explain the work you are showing at Lisson Gallery?

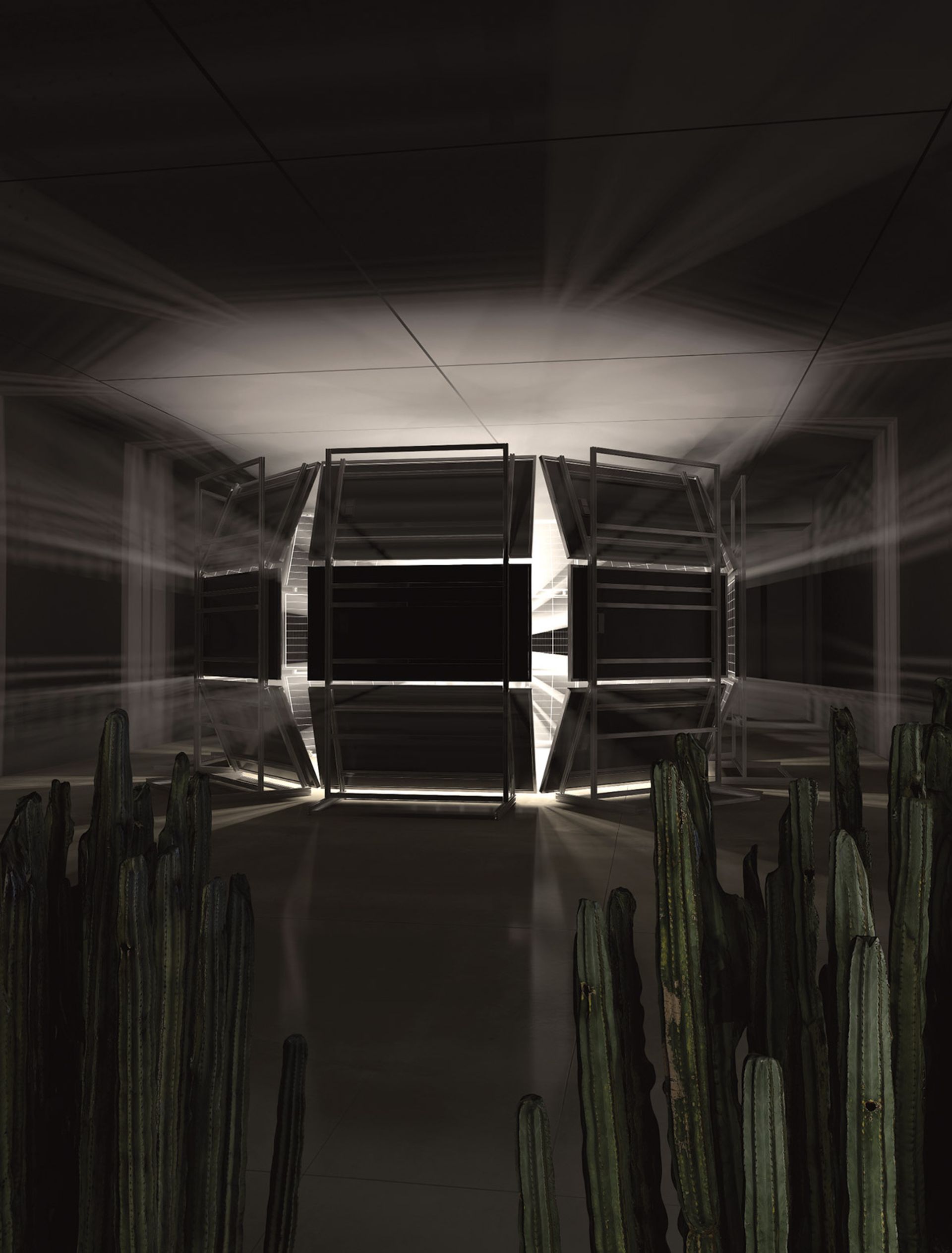

Haroon Mirza: I’m making a sculpture which is based on the concept of a Dyson sphere, a mega-structure that surrounds the sun or a star in order to harness the energy that a star produces. So in the gallery I’m creating a mini-sun made up of halogen lights that is surrounded by an array of solar panels. These solar panels will be generating electricity which in turn powers an ecosystem of works—sculptures that are both musical and of organic matter—that is “living” in the space.

What powers the central halogen sun?

The New York grid, basically. There was a plan to put solar panels on the High Line [park] above the gallery in order to have completely off-grid power, but it wasn’t possible in the time we had. But the amount of power that we’re actually using with the halogen lighting is pretty minor in relation to normal gallery shows.

What are you saying about the role of technology in the current climate crisis? While we seek technological solutions—of which the Dyson sphere is an extreme example—it’s also our obsession with technological advancement that has got us into this current mess.

Yes, the pursuit of energy is also the pursuit of technological advancement, which is harnessed to the idea that technology will save us. But we have really strong evidence that technology doesn’t necessarily save us but actually creates more extreme situations and more consumption. That’s the dilemma. So the question I’m asking is, what kind of species are we? Are we a parasitic species that goes around absorbing all the resources of a planet until we’ve used them all up, and builds structures around stars, and then goes on to another star—is that our species? Or are we actually a species that is symbiotic with the rest of nature and the biosphere? For me this question seems to be at the forefront of many things in terms of the climate issue and the energy issue.

Although you could by no means be described as an eco-artist, this new body of work does seem to demonstrate a more direct addressing and interrogating of environmental issues.

Yes, I think so. Post-Covid, we’ve all had this massive wake-up call and the environment has become such a dominant thing right now. In a way, it’s always been there as an undercurrent or a subtext in my work but now it’s more overt. The thing is, it’s everyone’s problem, not just the environmentalists’ problem. It’s my problem, it’s your problem and it’s definitely our kids’ problem, so we need to have a conversation about it. I’m not an environmental campaigner or an activist, and my work isn’t about the environment per se; it’s more about the biosphere. For me, the environment is a part of us anyway—we are what we do.

I’m very attracted to chaotic systems—waves, electricity, energy—that are present in nature

You are known as an artist who works with sound and light. But there seems to be a deeper and more enduring preoccupation with power and electricity that underpins everything you make.

It wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I figured out that electricity is actually my main medium. Originally I got hooked on the sound of electricity as a teenager. I remember first encountering electronic music—Acid House music—whilst under the influence of LSD. It was then that my infatuation with the sound of electrical signals began. And that slowly evolved into two things: a love of music in general, as well as the sound of the electrical signals, and then that spawned a practice. But what’s always going on underneath all that is a relationship to power, and to energy, and to the relationship between the two.

Can you elaborate on this multi-layered relationship?

Semantically they’re different, but there’s overlap between energy and power: you need energy to have power and electrical signals. The key for me is that it’s a circuit: there’s always a plus and a minus, which is conjoined to create the power. So the energy is like this twofold thing—it’s a positive and a negative charge, or a ground and a positive charge, that comes together to create power. And conceptually and metaphorically and as an analogy, that’s really interesting. Because in all of life and in the universe, ultimate power doesn’t come from just one source, it’s a combination of two or more things. Then philosophically this is interesting, because this negates monotheism. And then politically, those that have energy have power. There are just so many interesting things that can be extrapolated from this relationship.

Mirza’s visualisation of his project A Dyson Sphere, with cacti present as “psychoactive flora” © Haroon Mirza; Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

Electricity is a natural force: humans might generate electricity but it’s natural and unpredictable. It’s interesting that when you first started making art, this took the form of painted seascapes. Albeit in different forms, you still seem to be obsessed by waves and the unpredictability of nature.

Waves have been a preoccupation of mine since the beginning of my practice. There’s a thread that’s very clear, though I didn’t realise it at the time. From ocean waves to soundwaves, from electromagnetic waves to brain waves, I’m very attracted to chaotic systems—waves, electricity, energy—that are present in nature, and how our perceptual apparatus engages with them. I started painting seascapes and some of my earliest works were computer-generated seascapes with soundwaves representing land masses; now brainwaves and various neuro-oscillations are a more recent interest.

What made you leave painting? You were a DJ for a while too, weren’t you?

I still DJ from time to time—it’s more of a fun thing to do because I just love music. I studied painting at Winchester School of Art and during my time there I ended up reading Marshall McLuhan and [Jean] Baudrillard, and McLuhan’s essay on acoustic space. Then I started thinking about this sonic space that we don’t see and how that also makes up a huge part of our reality and the perceptual distinctions between visual space and acoustic space. So I got interested in the pragmatics of acoustic space and then in visualising that.

At times you’ve described yourself as a composer, rather than an artist. Why?

When I started working with sound it was initially a by-product in my work. I started by asking myself, how can I make these objects that generate sound, but then also structure and layer that sound? And these became my goals in terms of my practice. Then I thought [that] what I’m doing is composition, simultaneously composing in time and space, both visually and acoustically. So the term “composer” just seemed a bit more appropriate—but now it’s whatever works in the scenario. Artist is a blanket term but composer feels a bit more specific; a composer in a museum is different to a composer in a chamber, whereas a composer is an artist and so is someone who makes beautiful quilts.

Recently you were talking on a Gallery Climate Coalition panel about the role and impact of artistic problem–solving on the current status quo, in making people look at the world in a different way and finding significant solutions to existing situations. A case in point is the kickstarting of a wider awareness of solar energy in the oil state of Texas as a by-product of your collaboration with a solar power company on Stone Circle.

Yes, the starting point was: how do we power this thing in the desert? It wasn’t: how do we get solar power into Texas where most of the energy comes from oil? But then the side-effect was amazing, it was, like: “Look, you can make energy from the sun!” And many [local] households switched to solar energy. And that’s the powerful thing about art: artists being able to propose things that actually provide practical solutions to things or open up a new awareness of something, or open up a new way of thinking about something. Sometimes it happens as a very programmed part of the work, and all respect to those artists who make work that incites some sort of awareness. But the majority of the time it comes out of an accidental side-effect, and for me that’s one of the most powerful things about being an artist.

Biography

Born: 1977 London

Lives: London

Education: 2007 MA Fine Art, Chelsea College of Art and Design; 2006 MA, Design Critical Practice and Theory, Goldsmiths College; 2002 BA, Painting, Winchester School of Art

Key shows: 2021 Liverpool Biennial; 2020 CCA Kitakyushu, Japan; 2019 John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, UK; Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne; Sifang Art Museum, Nanjing; 2018 Ikon, Birmingham; Ballroom Marfa sculpture commission; 2015 Museum Tinguely, Basel; 2014 Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye, Poissy, France; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; 2013 The Hepworth, Wakefield; Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art; 2012 New Museum, New York; Camden Arts Centre, London; 2011 54th Venice Biennale

Represented by: Lisson Gallery

• For A Dyson Sphere, Lisson Gallery, New York, 13 January-12 February; lille3000, Lille, France, 14 May-2 October