Until 6 February, The Curve, Barbican, EC1

The Mumbai-based Shilpa Gupta, one of India's most notable contemporary artists, has long been concerned with visualising political divisions and amplifying the plight of the voiceless in her work. Gupta's first major UK solo show ties these two threads together tightly—though not neatly—in an impassioned defence of free speech. The exhibition's largest work, the 2017 sound installation For, In Your Tongue, I Cannot Fit, fills a dimly lit room with leaves of paper printed with poems by incarcerated dissident writers from around the world. These are punctured upon rows of upright metal stakes; from 100 low hung microphones the poems are spoken aloud, sometimes alone, sometimes in unison. The chorus occasionally chants, its sound swelling into cacophony, before dissipating into whispers and breath.

Ten of these printed poems hang on the walls of the Curve's main gallery, more legible in the bright light, next to single-line pencil drawings on papers. These depict moments of embrace, quiet solitude, and abuse at the hands of fascist governments. Those familiar with Gupta’s earlier work will detect her interest in the political cartography, specifically that of the divided South Asian subcontinent. When studying her delicate, unbroken lines, one can observe every breath and quiver of the hand that drew them. As ever, Gupta likes to draw the eye past a work's formal qualities and locate the human behind the mark, the person behind the process.

Further works in the show include a bronze cast of the interior of a mouth and an animated signboard similar to those found in Indian railway stations. These provide a succinct insight into the personality that defines Gupta’s work: terse, serious, sincere and deeply empathetic. Although some work appears overly poetic (in one, Gupta has literally spoken words of poems into empty medicine bottles as a way to preserve them), one need only consider the immense threat that faces free speech the world over to forgive this. It is difficult in our current moment to understate the importance of holding those in power to accountability, in which ever way we can.

• Gupta’s first UK solo commercial exhibition has also just opened at Frith Street Gallery (until 22 January). —KJ

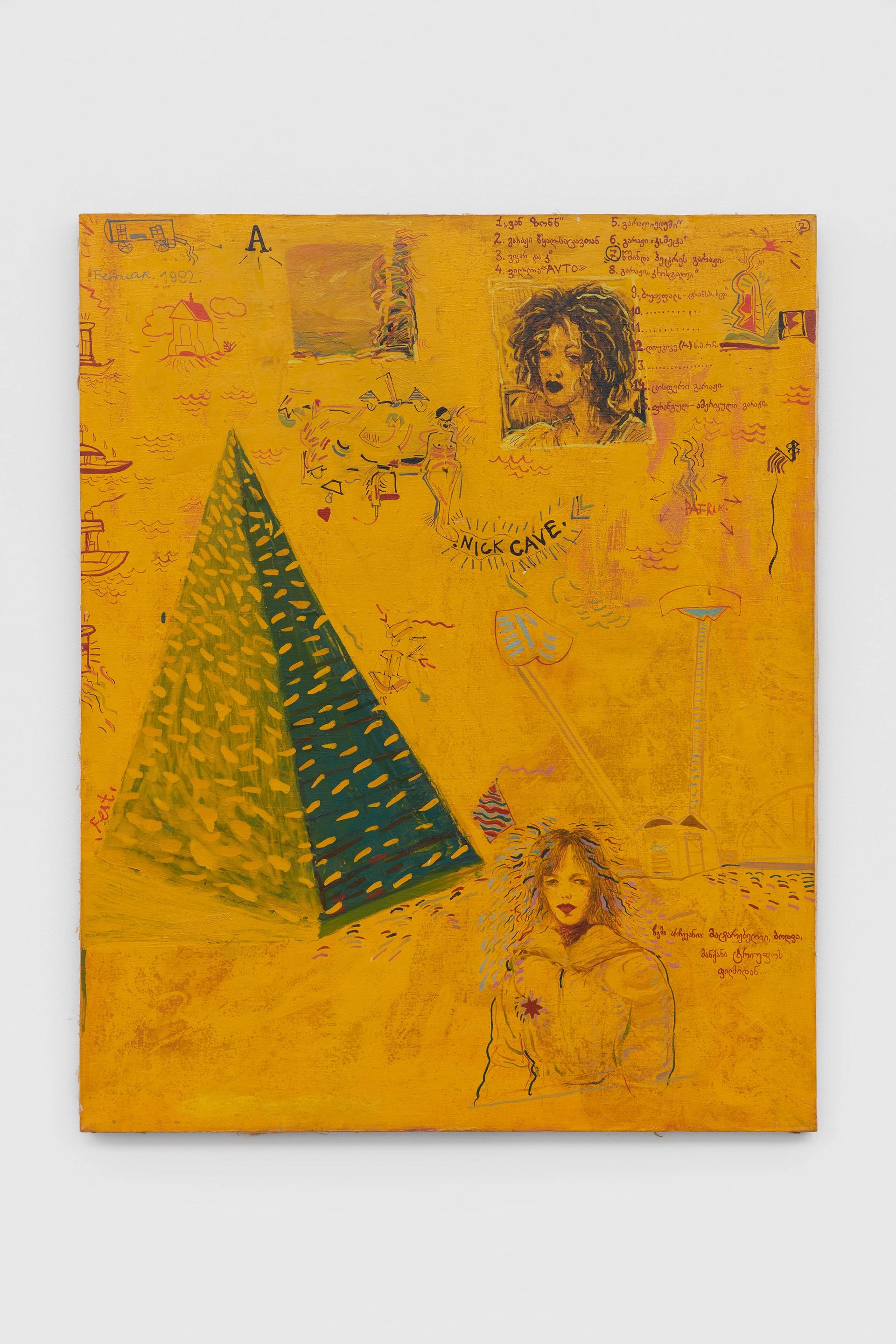

Karlo Kacharava's Nick Cave (1992). The Estate of Karlo Kacharava, Tbilisi, Georgia and Modern Art, London

Karlo Kacharava: People and Places

Until 17 December, Modern Art, 4-8 Helmet Row, EC1V 3QJ

The Georgian painter, poet and art critic Karlo Kacharava spoke about his death constantly. Which makes it all the more ominous that he died from a brain aneurysm in 1994, aged 30, one year after being hit in the head during a robbery. In his home country, and the surrounding Caucasus region, Kacharava is well known, and is credited with pioneering a new Georgian avant-garde movement during and after glasnost. However, he is virtually unheard of in Western Europe (although a couple of posthumous New York shows at Joyce Goldstein in the 1990s, and Metro Pictures in 2017 have given him a cult presence in the US). This makes his first UK show at Modern Art (which announced representation of Kacharava's estate earlier this year) all the more exciting.

In this survey, his distinctive visual world is well explained through oil paintings which, with their abject, spiky style, draw heavily from "degenerate" German Expressionist artists such as George Grosz and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, as well as the Italian Transavanguardia. Meanwhile, Kacharava's melancholic drawings take inspiration from modular comic-book cells and appear sewn together. Among the hodgepodge of Western influences that seem to have crept under the Iron Curtain and into Kacharava's milieu are French New Wave Cinema and the work of Susan Sontag, whose famous 1966 book of essays Against Interpretation is name checked in a 1992 painting.

What makes this show so compelling is that it not only provides insight into Kacharava’s interior life, but that it also acts as a tableau of the complicated attitudes towards Georgia's re-opening to the West. The artist is both celebratory and suspicious of what other narratives might fill the vacuum left by the crumbling Soviet empire. Along with volumes of poetry and art criticism, Kacharava left behind a body of works of art that numbers well over 1,000 and which Modern Art has described as "oceanic", meaning we have likely just scratched the surface of his presence on our shores. — KJ

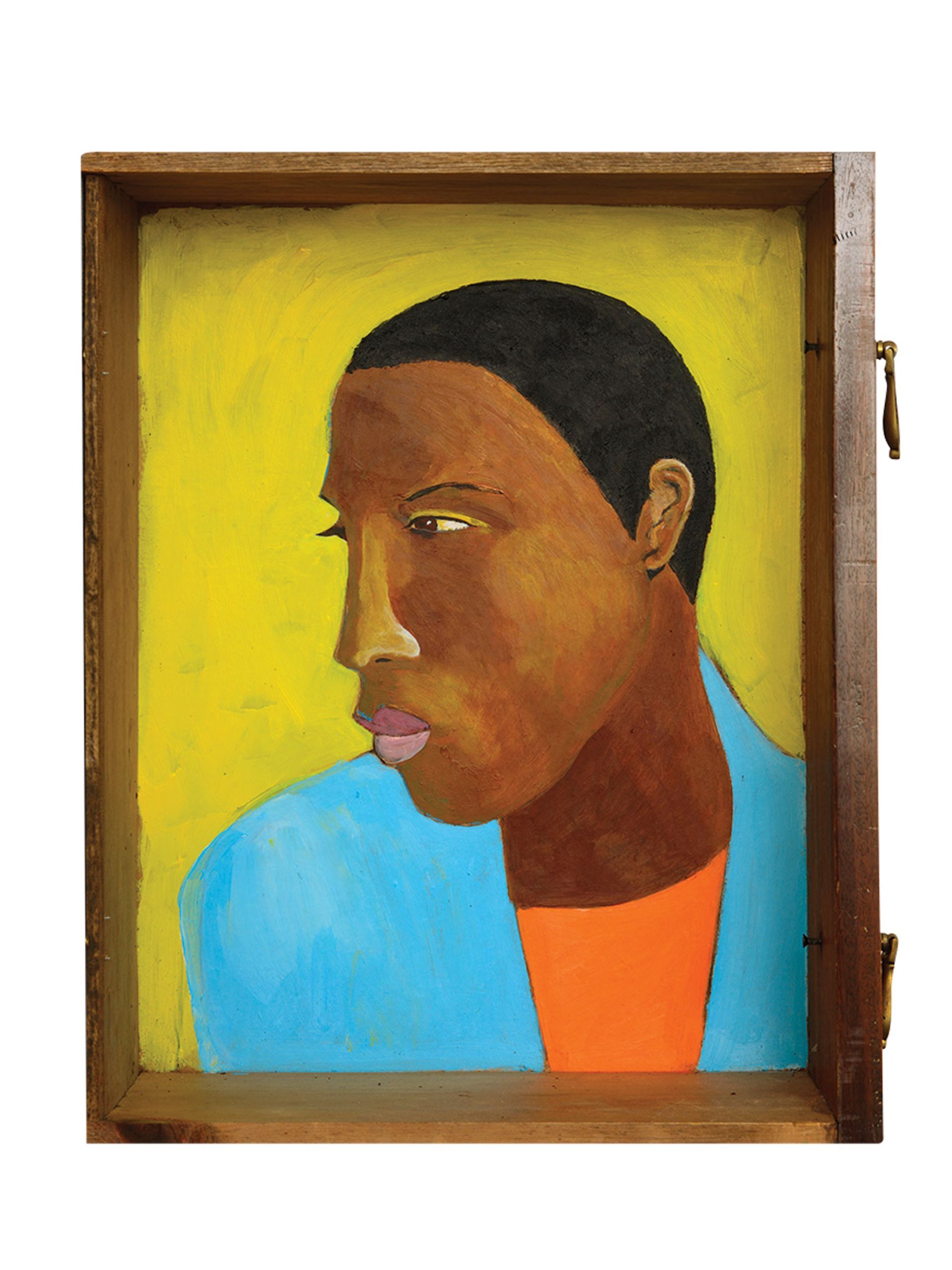

Man in a Shirt Drawer (2017-18)© Lubaina Himid

Until 3 July 2022, Tate Modern, Neo Bankside, SE1 9TG

The largest solo show to date of the Turner Prize-winning artist and cultural activist Lubaina Himid uses her early interest in the stage to thread together her paintings and installations. One of the most unusual aspects of the exhibition is the use of sound to augment the experience of Himid’s works. Though she never intended to create operas, they did expose her to the way that music can have an emotional effect on narrative, and five sound installations will run through the show—some created by Himid’s fellow artist and teacher Magda Stawarska-Beavan, some a collaboration between the two. Another thing that sets this exhibition apart is that, instead of explanatory texts, there will be open-ended questions embedded in the works and on the walls. Questions such as “What are monuments for?” and “How do you distinguish safety from danger?”, which are, as Wellen says, “easy to ask, very difficult to answer”. — CH