The American fugitive artist Ray Johnson, known for his subversive collages and pioneering mail art, killed himself in 1995, at the age of 67, by jumping off a Long Island bridge. In what could only be called an anti-art career, marked by resistance to every kind of recognisable art authority and genre, he nonetheless managed to produce a substantial body of work.

Now that work has become the focus of a number of establishment events, including a major photography show next summer at New York’s Morgan Library & Museum and an overview of his active early decades opening this month at the Art Institute of Chicago, titled Ray Johnson c/o.

The photographs, mostly from the 1990s, will reveal a previously unknown side of Johnson’s work, while the Chicago show features some of his best-known images, such as Oedipus (Elvis Presley #1), a collage from 1956-58, in which the artist modified a publicity close-up with eerie red blocks and splats, and a bit of eroticising blue around the eye.

The occasion for the show is the Art Institute’s 2018 acquisition of the William S. Wilson Collection of Ray Johnson, a rich resource compiled by Johnson’s friend and correspondent, and—the show curators suggest—collaborator. In receiving Johnson’s weird and wily collages and flyers through the mail, and then compiling and cataloguing them, Wilson went from co-conspirator in Johnson’s attempt to bypass art-world authorities to a leading authority on his art.

Criss-crossing movements

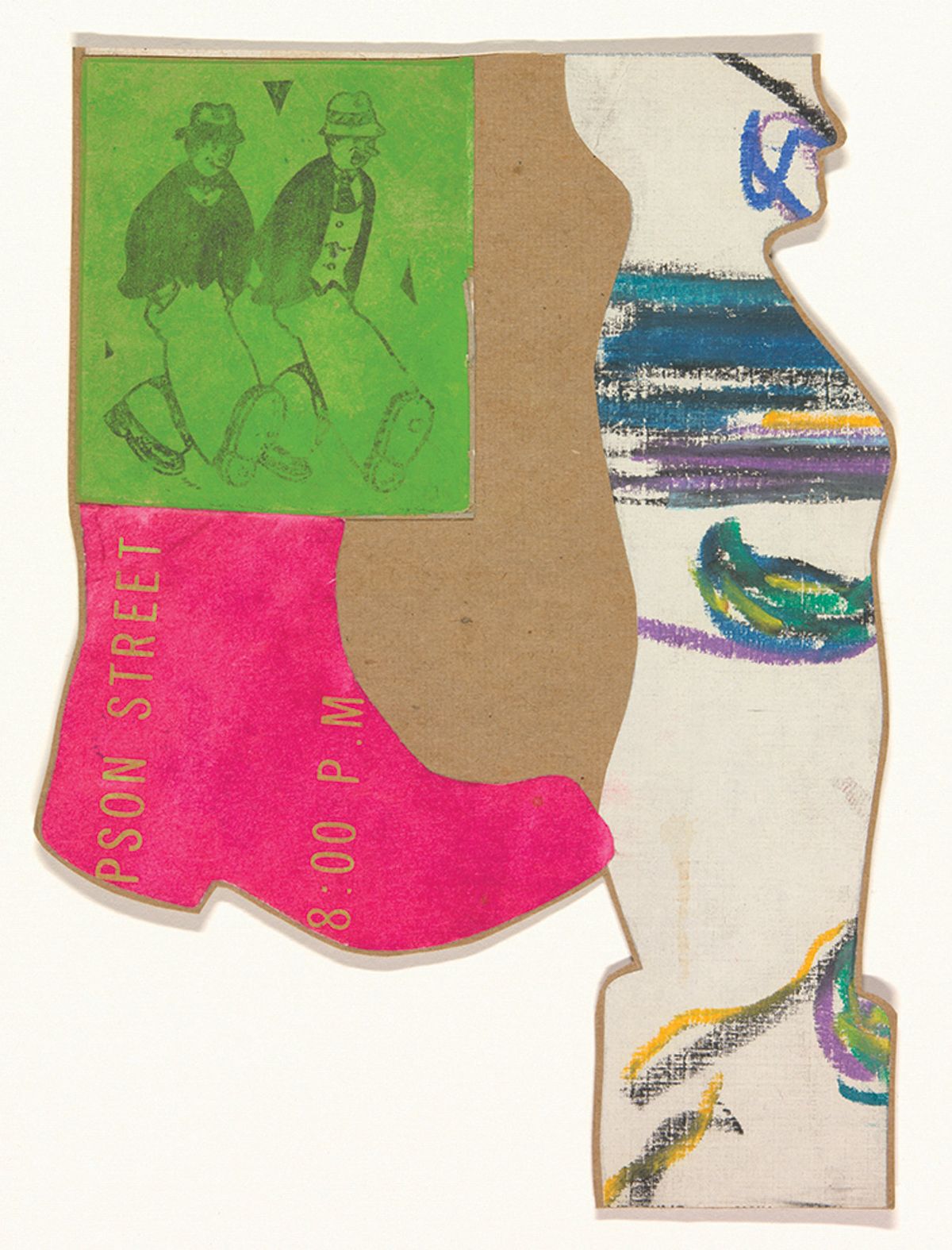

The show features around 250 works and objects, spanning nearly the whole of Johnson’s working life, but a main attraction will be a number of early collages that have never before been on public display, such as Untitled (Pink Boot), from around 1955. Johnson’s keen sense of composition is on display in another previously unexhibited work, the 1968 diptych collage Untitled (Black Cap), which criss-crosses Pop Art and Surrealism with a distant wink at religious art.

Johnson had a crucial stint at North Carolina’s progressive Black Mountain College, where he was taught by Josef Albers, and his subsequent ransom-note like creations, pieced together out of American ephemera, had a grounding in European Modernism, says the Art Institute curator Caitlin Haskell, who organised the show together with colleague Jordan Carter.

However, the artist’s career-long defiance has prompted some soul searching among the curators, says Haskell. “His energy is antagonistic to everything we habitually do in the museum world. To be true to that vision has been incredibly inspiring—but also made us question the conventions of our workplace.”

• Ray Johnson c/o, Art Institute of Chicago, 26 November-21 March 2022