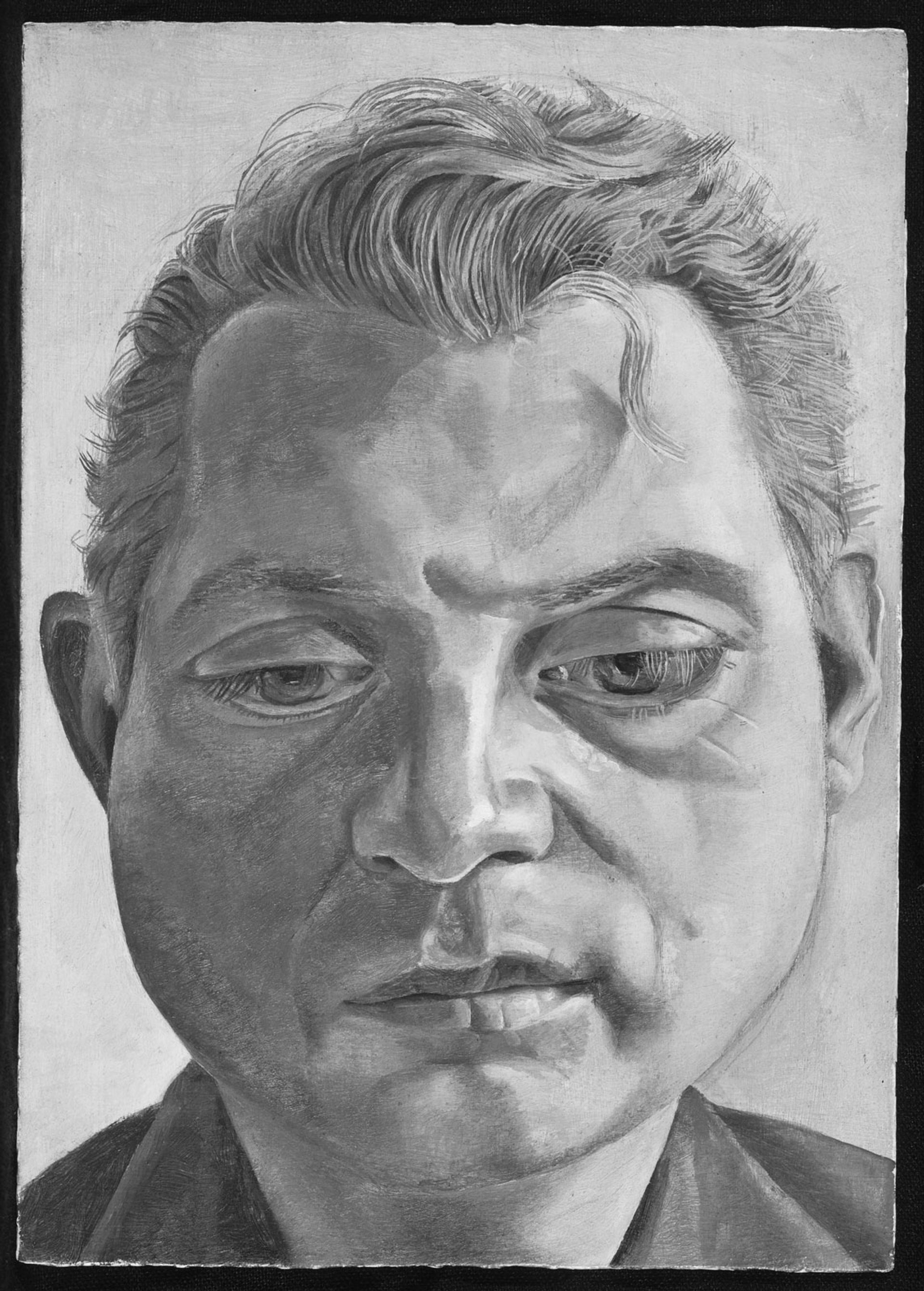

A photograph taken shortly before “the most important portrait of the 20th century” was stolen is being published for the first time this month in a new book. Lucian Freud’s 1952 portrait of his friend and fellow artist Francis Bacon was stolen in 1988 during an exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and has never been recovered. Now, more than three decades later a photograph taken moments before the work went missing is being published in a new book of Freud’s copper paintings.

Although the installation photograph was in the Berlin museum’s archive, it was not until David Scherf was researching for his book Lucian Freud: the Copper Paintings that anyone realised quite how significant it was. When the museum first sent him the image, it was undated. Scherf asked if they had more information and the archivist scanned and sent him the contact sheets of the installation shots. “On the back was the name of the photographer and the date,” Scherf says. It read R. Friedrich and was dated 27 May 1988, the day of the theft. “Then it became interesting.”

Francis Bacon (1952) by Lucian Freud was stolen in 1988 and never recovered. Here it is reproduced in black and white at the request of the late artist © Tate

After that initial discovery, Scherf spoke to Andrea Rose, the curator of the 1988 exhibition, and her husband, the critic and Freud biographer William Feaver. They said that the photographer who had come in that day “took the photos of the exhibition at around 11.30am”. A security guard reported the theft at 3pm and the museum’s doors were closed and visitors were questioned and searched. But nothing was found. One visitor claimed that the spot where the painting should have been, was already empty shortly after noon. “It became clear that there was just a brief period of time between the photo and the theft, possibly only minutes,” Scherf says.

According to Feaver’s recent two-part biography, The Lives of Lucian Freud, on the day that the theft took place only one of the “requisite three guards […] had been posted in the part of the gallery where the painting hung”. Like most of Freud’s copper paintings, the Bacon portrait was small, measuring just 17.8cm by 12.7cm, and would have easily been tucked into a coat or hidden in a bag.

A reward of 25,000 Deutschmarks was offered for any information that would lead to the recovery of the painting, which belongs to the Tate (the museum has never made an indemnity claim for the work). The fate of the work remains a mystery despite Freud’s growing fame and further appeals including a “wanted” poster that the artist made in 2001 and had plastered around Berlin offering a DM300,000 reward. Freud appealed to the thief ahead of his major retrospective at the Tate: “Would the person who holds the painting kindly consider allowing me to show it in my exhibition next June?”

Lucian Freud with Francis Bacon in Bacon's London studio in 1953 © Daniel Farson / Marlborough Gallery

Freud was marked by the theft and requested that the lost image only be reproduced in black and white (as it is in Scherf’s book and also on the Tate website). In a 2008 review of Tate’s Francis Bacon exhibition, the Australian critic Robert Hughes recalled a conversation with Freud shortly after the portrait had been taken. The artist suggested the thief had not stolen the work because it was by him but because “he must have been crazy about Francis. That would justify the risk.” Hughes called the work an “unequivocal masterpiece”. Nicholas Serota, who became the director of Tate the same year it was stolen, called the painting “the most important portrait of the 20th century”.

The painting was one of only two portraits that Freud painted of Bacon and all the more unusual for having been painted on copper. Scherf’s new book, with an essay by Martin Gayford, brings together all of Freud’s known paintings on copper, half of which were hardly known about when he began his research in autumn 2011. “I spoke to people who were very knowledgeable about [Freud’s] oeuvre and they said there might be a handful [of paintings on copper]”.

Lucian Freud's The Grand Union Canal, Paddington (1952) has never been reproduced before © image: Private collection; © artwork: Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

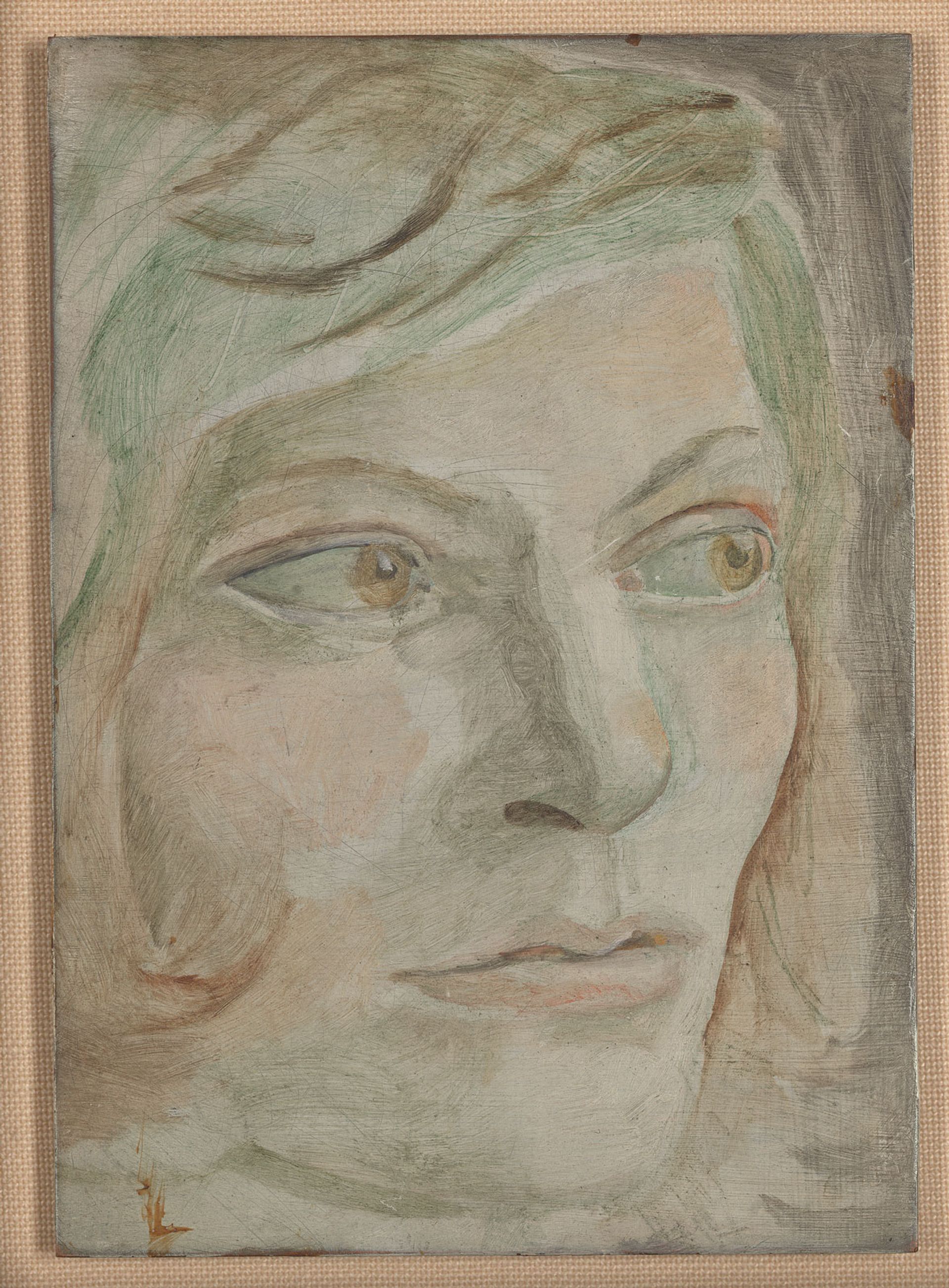

After almost a decade of research, and having worked closely with the art historian Catherine Lampert, who is compiling Freud’s catalogue raisonné, Scherf managed to track down 14 copper paintings made between 1949 and 1953. All are included the book and two are being reproduced for the first time: a rare landscape titled The Grand Union Canal, Paddington (1952) and Sketch for a Portrait (Henrietta Moraes) (around 1952).

Scherf writes in the book that Freud’s copper paintings are “psychological and forensic examinations”. The mostly small, postcard-sized works were painted in great detail with Freud sitting right up close to his subjects. Their size also meant they were easily transported and allowed Freud to paint while away from his studio, such as during a hunting trip to Northern Ireland (Brace of Pheasants, 1952-53) or in his cabin while on a cross-Atlantic voyage (Self-Portrait, 1953).

Lucian Freud's Sketch for a Portrait (Henrietta Moraes) (around 1952) is one of only 14 known copper paintings by the artist © image: Yale Center for British Art, New Haven; © artwork: Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images

Although Freud only painted on copper for a few years, starting out with leftover copper from etchings, Scherf believes that there may well be a few more out there. “I’m quite positive that Freud painted more than 14. But the way he worked, not a lot more.”

Scherf is also on the lookout for more images of the lost Bacon portrait. The work was bought by the Tate in 1952 and was exhibited several times before its theft, including at the Venice Biennale in 1954. The 1988 Berlin exhibition was the final leg of a touring show organised by the British Council that had stopped off at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Hayward Gallery in London. Scherf says he knows of only three installation shots of the Bacon—the one in Berlin, and one each at the Hirshhorn and Hayward—and is appealing for anyone who may have snapped it during one of the shows to get in touch with The Art Newspaper (info[at]theartnewspaper.com).

Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings

• Lucian Freud: The Copper Paintings, David Scherf and Martin Gayford, Less Publishing and Yale University Press, 80pp, £30 (hb)