Henri Matisse had no new paintings to show Etta Cone in 1933 when she visited him at his studio in Nice. He usually reserved a few canvases for her, since this devoted collector had been making annual trips to see him from her progressively cluttered apartment in Baltimore, Maryland. This time, he was taking a break from his easel after struggling for two years with The Yellow Dress (1929-31). Cone knew this painting well, actually; she’d bought it the year before and hung it in her front room.

Matisse did not want to disappoint Cone, and so instead of new paintings he produced a customised tableau vivant: he had his model for The Yellow Dress return to the studio and wear the gown she had worn for the painting, seated in the same spot. “Cone was thrilled by this very personal gesture,” says Katy Rothkopf, the director of the Baltimore Museum of Art’s Center for Matisse Studies and the co-curator of a new exhibition about the collector’s relationship with the artist, titled A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone and Baltimore.

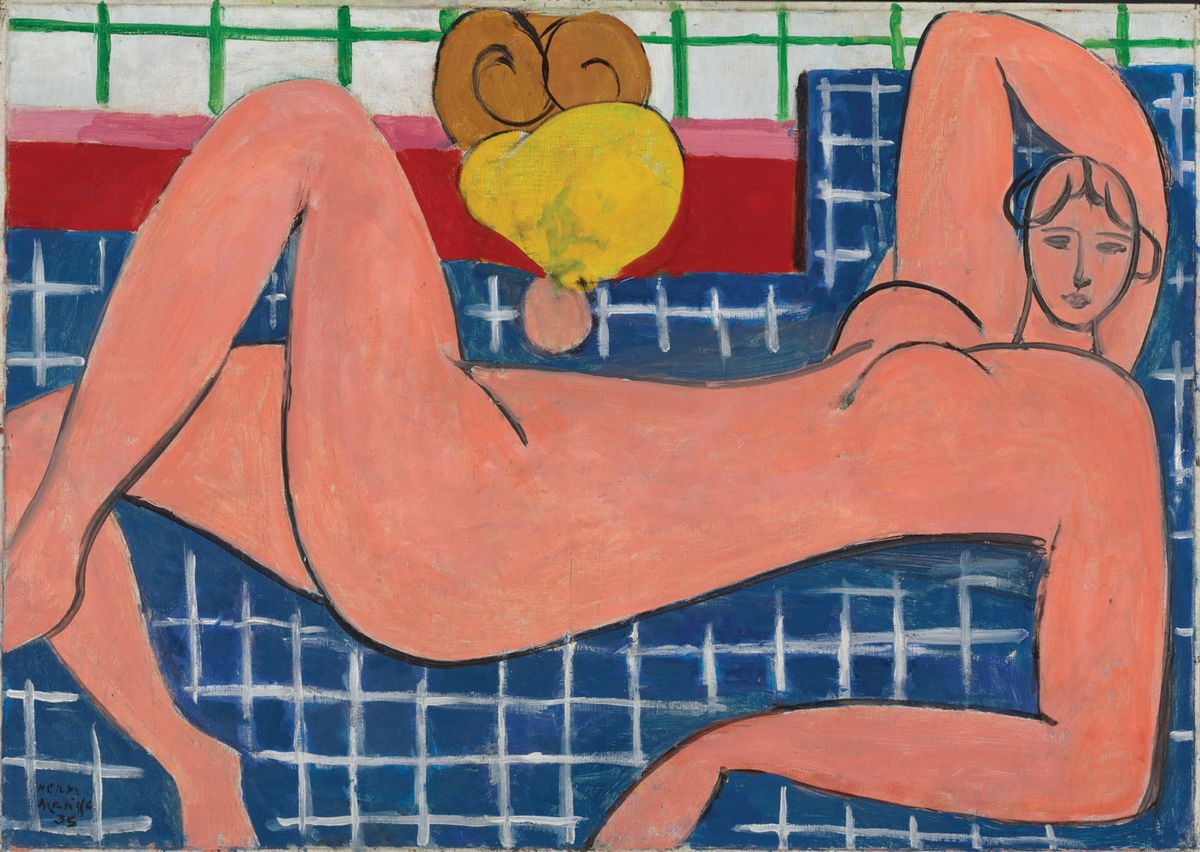

Henri Matisse's The Yellow Dress (1929-31) © Succession H. Matisse, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS) New York

This private moment between an artist and a collector, whose relationship spanned 43 years and a transatlantic expanse, is one of many shared in the show of around 160 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and illustrated books. Planned for several years, it anticipates the opening of the museum’s Ruth R. Marder Center for Matisse Studies this December.

“For Cone, being a collector, and one focused on Matisse’s work in particular, was a tremendous pleasure that gave her life focus and a profound sense of purpose,” writes Rothkopf in the exhibition catalogue. “For Matisse, Cone was the most loyal, consistent and supportive of patrons.”

Etta Cone in her apartment in Baltimore, Maryland (around 1930-40) Courtesy of Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Archives and Manuscripts Collections, BMA

They met in 1906 when the American collector Sarah Stein brought Cone to Matisse’s Parisian studio, a year after she and her husband Michael bought their first painting by the relatively little-known artist. Cone only purchased two drawings that time, but stayed in touch and started collecting Matisse’s work in depth in the 1920s. When the Frenchman travelled to the US in 1930 to paint a large-scale mural for another collector, Albert Barnes, he trekked from Philadelphia to Baltimore to see how Cone and her sister, Claribel, lived among his colourful odalisques.

Cone was still adding Matisses to her walls right up until her death in 1949, and the lengthy correspondence between the two tells a story of friendship. “It was your work that has filled my life,” Cone wrote in a letter to Matisse in 1946.

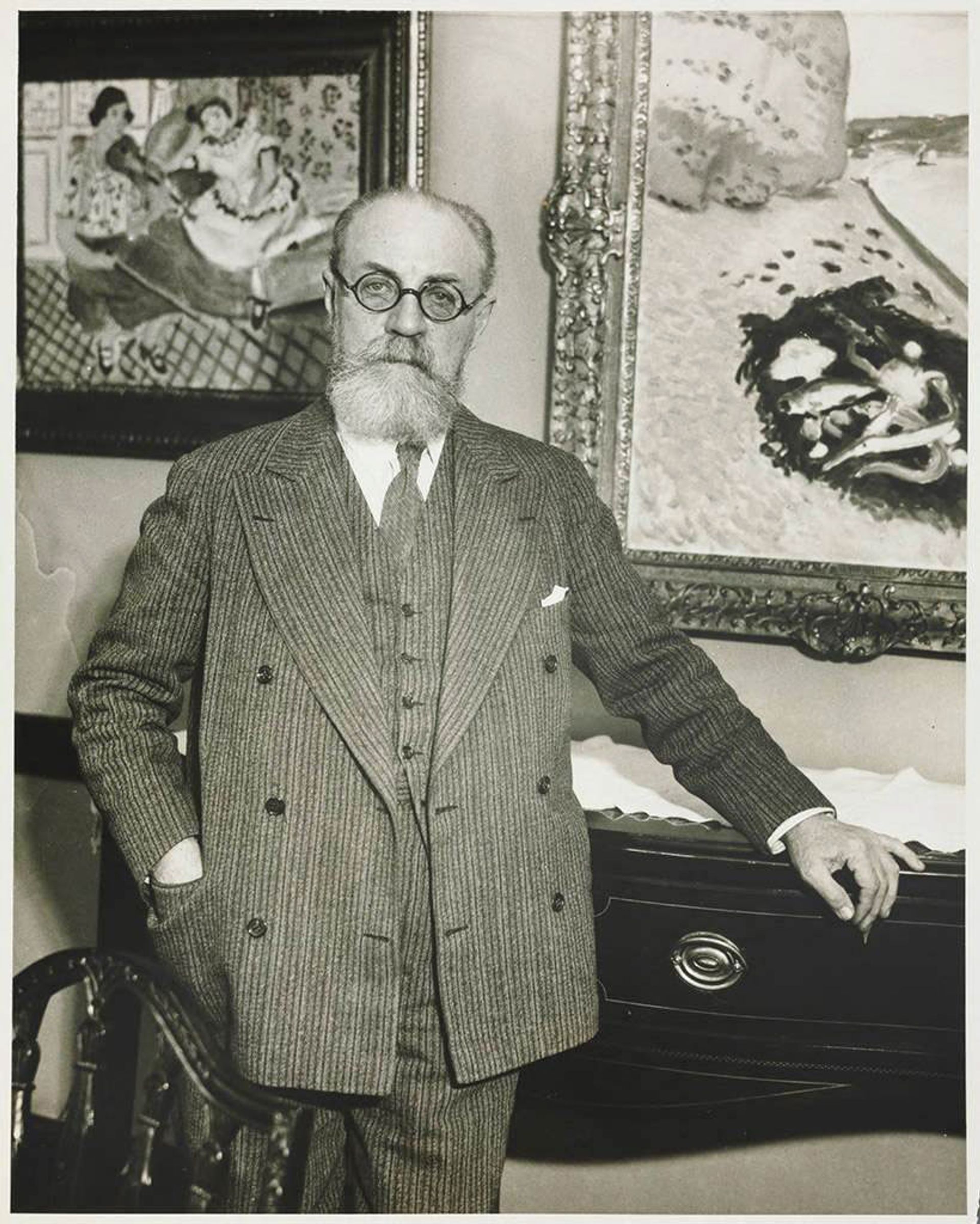

Henri Matisse in Etta Cone's apartment in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1930 Claribel Cone and Etta Cone Papers, Archives and Manuscripts Collections, The Baltimore Museum of Art.

Cone’s rapport with Matisse made her unique among his major patrons. “Unlike supporters like the Steins and [Sergei] Shchukin, she acquired Matisse’s work for many more years and was able to keep her collection until her death,” Rothkopf says. “Cone also made sure that [Matisse’s] work would be accessible to museum viewers in perpetuity.”

Of the more than 700 Matisse works that the Cone sisters amassed, they bequeathed around 600 to the Baltimore Museum of Art, in what is considered a crown jewel of the institution’s collection. The museum continued accessioning Matisse works after this 1949 gift and now has more than 1,200—the largest collection of his works in any public institution.

This exhibition pays equal tribute to the Modernist painter and his ardent patron, whose legacies hinged on each other. “M. Matisse, I helped to ‘make’ you,” Cone once complained to Matisse about his swelling prices, on a day when his studio was not bare. The artist cheekily replied, “No, Mme. Cone. I made you.”

• A Modern Influence: Henri Matisse, Etta Cone and Baltimore, Baltimore Museum of Art, 3 October-2 January 2022