Tacita Dean has an exquisite sense of timing—or, rather, of time itself, her true subject. It begins and then it runs out, everywhere but in her films, which end where they start. Mortality is at issue. So is history and its traces, most of which would likely disappear if not for the archiving/excavating gene in artists like Dean. Her relentless campaign to put obsolescence out of business, particularly when it comes to analogue media, tugs at the heart. It also has led to a varied and ruminative trove of works that cling to the mind’s eye long after the body has moved on.

A substantial number are on display in her museum-worthy show at Marian Goodman, the opening of which kickstarted the revived autumn season in New York and brought out such notable curatorial talents as Sheena Wagstaff (The Met), Lynne Cooke (the National Gallery), Stuart Comer (MoMA) and Silvia Karman Cubiñá (the Bass). Among them were three representatives of the Getty Center, where Dean incubated much of what is on view during a year-long research project that ended up consuming her over seven. Also present was the artist Matt Mullican, whose mother, Luchita Hurtado, was the subject of the remarkable One Hundred and Fifty Years of Painting, the latest in Dean’s growing body of films about art eminences whom she has captured so close to their final passing that her intimate portraits stand, at least symbolically, as their last words.

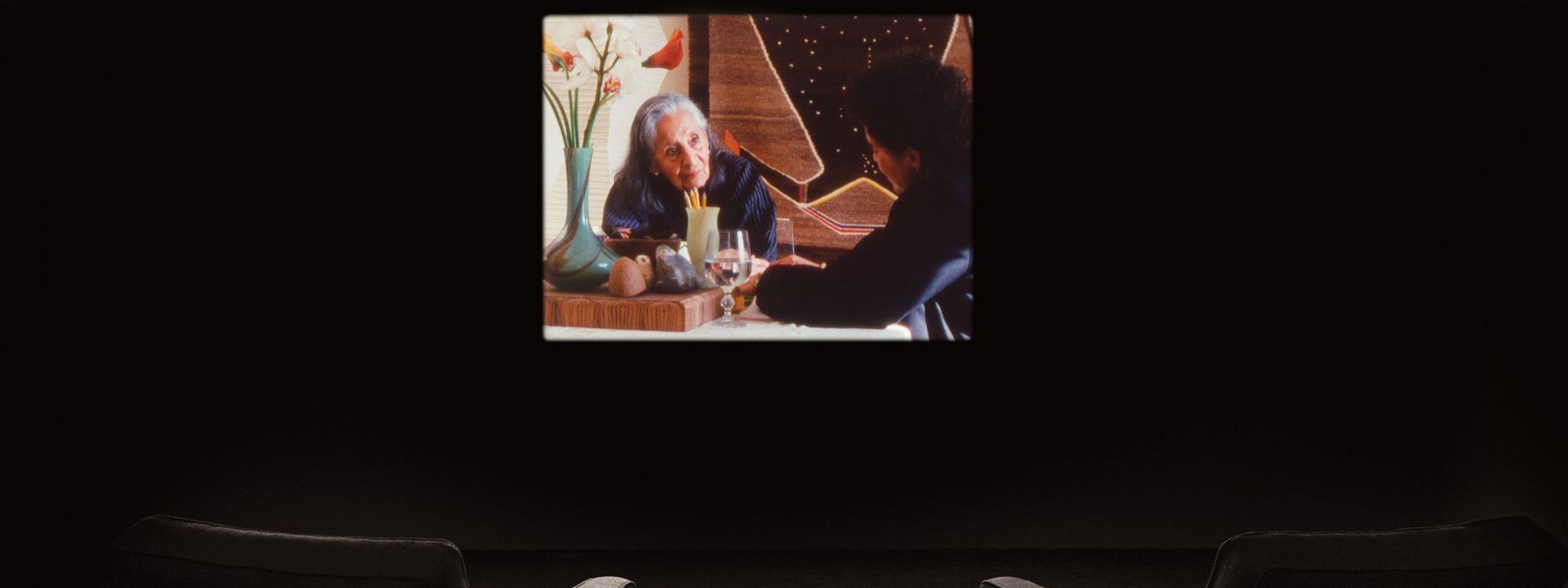

In January of 2020, a minute before Covid, Dean went to Santa Monica to shoot Hurtado, who was then 99. A previous subject, Julie Mehretu, who is half Hurtado’s age but shares the same the birthday, was her interlocutor. “Can you talk about loss?” she asks Hurtado, and out spills one startling, cosmic or in every way profound story after another, accompanied by closeups of both painters’ gesturing hands and expressive faces: how Hurtado had 13 cats and a Picasso drawing that was stolen by a friend of a friend; how she internalised the death of a six-year-old son; how she made drawings or paintings nearly every day, something she chose not to share with the world or her third husband, the painter Lee Mullican, father of her two surviving sons, Matt (who appears in the film) and John, a film-maker.

Tacita Dean's film One Hundred and Fifty Years of Painting on the artist Luchita Hurtado

Hurtado remained essentially unknown to the contemporary art world until Paul Soto, a young dealer with a tiny gallery in Los Angeles, brought her paintings to market. Hurtado was already in her 90s and was famous by the time she died, in August 2020, a few months shy of her centenary, when she was repped by Hauser & Wirth. In Dean’s film, she describes her path as a lighted road with darkness on either side and concludes on a comforting note. “It gets more interesting,” she concludes. I didn’t want the film to end. Thanks to Dean’s looping structure, it didn’t.

But her show at Goodman does have showstoppers, beginning with her ginormous, solarised-looking, penciled photographs of trees the size of the Los Angeles buildings they front. Trees make frequent appearances in Dean’s work, as do moonrises and sunsets, clouds, and mountainous landscapes that grow outside of time. This is the situation in Pan Amicus, the second film in the show and the basis for several chalk drawings on blocks of salvaged Victorian blackboards that incorporate evidence of their past. They are pictures of infinity, mute, unlike her film, where the sound of wind and birds and rustling leaves is as paramount as the movement of the earth around the sun.

Another set of drawings on photographs relate to Dean’s designs for The Dante Project, her commission from the Royal Opera House for an upcoming ballet based on Dante’s Inferno, choreographed by Wayne McGregor. (It premieres in London on 14 October.) At the scarily crowded dinner for Dean that followed her opening, I asked what she was planning to do for the ballet. “I don’t know yet,” she said, but I didn’t believe her. On the other hand, when she started Monet Hates Me, her “exhibition in a box”—50 items plucked from the Getty archives—she didn’t know what she was looking for, and that turned out really well, beginning with her discovery of the key to Rodin’s studio in Paris. “I’m open to chance,” she said.

The box is one of two editioned projects that consumed the artist during her 2020 pandemic lockdown in Berlin, where she lives. The other, also on display, salon-style, at Goodman and (through 27 Feburary 2022) at its commissioner, the Hepworth Wakefield, is Significant Form: 130 unframed photographs on paper of Dean’s collection of vintage postcards. Not surprisingly for this historicising artist, many show places and structures that are endangered or already gone.

Like the rest of her show, it is not about nostalgia, or grief, but how artists negotiate the passage of time — through their bodies and the media that give purpose to their lives.

• Tacita Dean: The Dante Project • One Hundred and Fifty Years of Painting • Pan Amicus • Significant Form • Monet Hates Me, until 23 October, at Marian Goodman Gallery

• For an interview with Tacita Dean, listen to our podcast A brush with...Tacita Dean