Given that the Frick Collection is not an encyclopaedic museum, its acquisitions are generally driven by a honed instinct for accentuating the core strengths of the trove of mostly European masterworks collected by its impulsive founder.

Now the New York museum is celebrating its most significant gift of drawings and pastels to date: 26 sterling works, ranging from a sketch for John Singer Sargent’s renowned 1884 painting Madame X to an emotive 1784 pastel of a woman’s head by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun that leavens the preponderance of male artists in the Frick's collection.

The promised gift, from the New York collectors Elizabeth and Jean-Marie Eveillard, will go on view in the fall of 2022 at the museum’s temporary home at Frick Madison. It includes notable works by artists already represented at the museum–Goya, Degas, François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Thomas Lawrence and Jean-François Millet–and by others who are not, such as Sargent, Vigée Le Brun, Gustave Caillebotte, Maurice Quentin de la Tour and Jan Lievens.

Elizabeth “Betty” Eveillard, chair of the Frick’s board, and Jean-Marie Eveillard, a former trustee at the museum, have been amassing European works on paper since the 1970s and recently began discussing future homes for their collection, says Xavier Salomon, the Frick’s deputy director and chief curator. “It all began with us going around their apartment” last year and “discussing what would work for the museum,” he said in an interview. “The fact that they gave the Frick first choice was very generous.” The promised gift comprises 18 drawings, five pastels, two prints and an oil sketch.

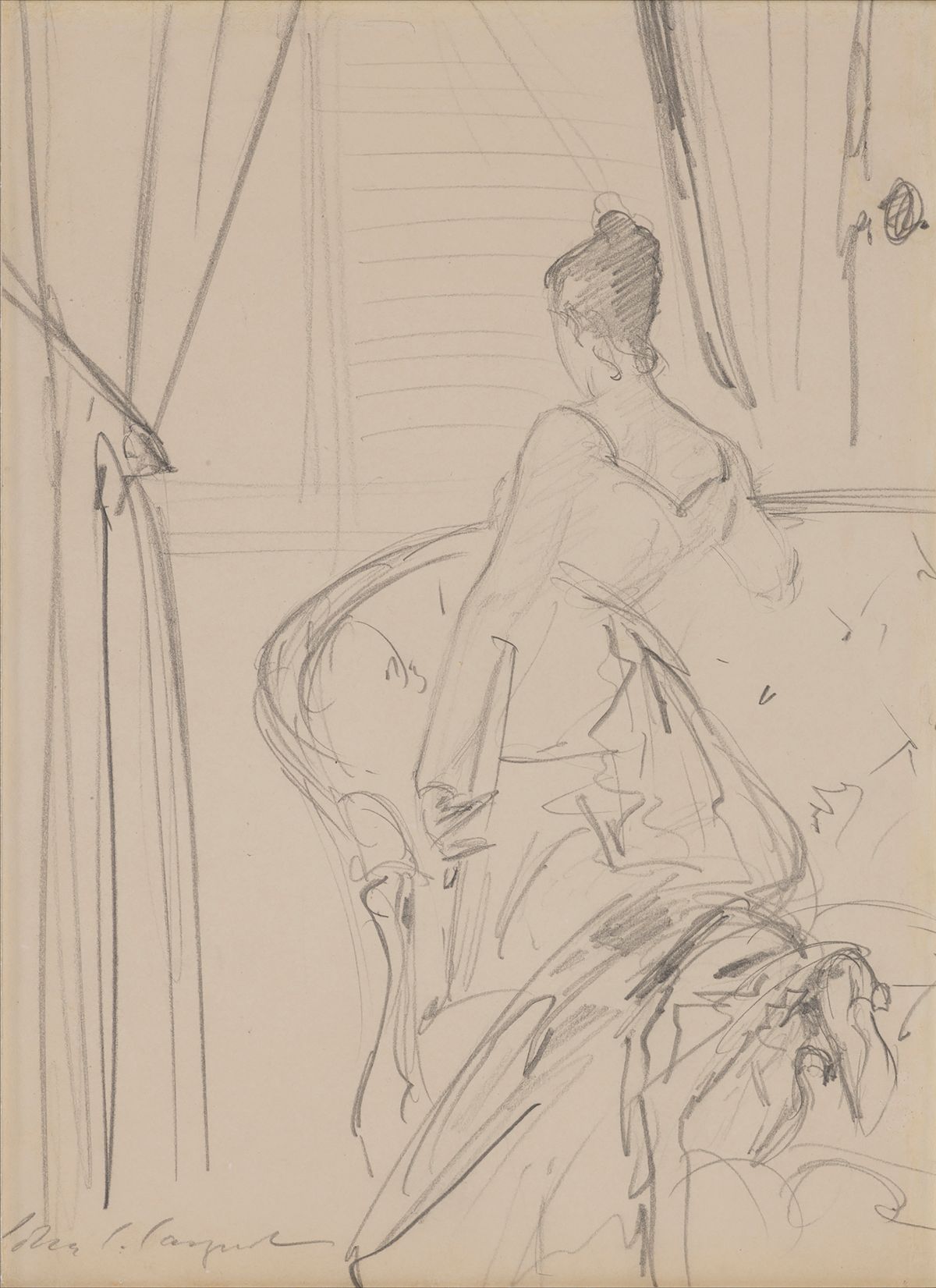

Salomon says that Sargent’s drawing Virginie Amélie Avegno, Mme. Gautreau (Mme. X) was the first important work acquired by the couple and one of around a dozen studies that Sargent made for his Madame X oil portrait, purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1916. The subject, the Louisiana-born Paris socialite Madame Pierre Gautreau, “was an eccentric woman, very brash, someone everyone talked about,” the curator says. “She was someone who was defining tastes by going against the current.”

In the Met’s canvas, which depicts Madame Gautreau standing upright in an evening gown with her head turned, Sargent emphasised her rebellious style by showing the right strap of her gown slipping from her shoulder. It took him over a year to finish the painting due to the challenges of capturing her “unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness”, the artist has been quoted as saying. The work caused a scandal at the Paris Salon of 1884, and Sargent later repainted the shoulder strap.

In the drawing, however, the artist sketches the socialite kneeling on a couch and facing a shuttered window. “What you see is a very different image from what he finally does,” says Salomon. “What I love is that it’s a strange composition. It’s clear that he’s trying to get to know her by drawing her.”

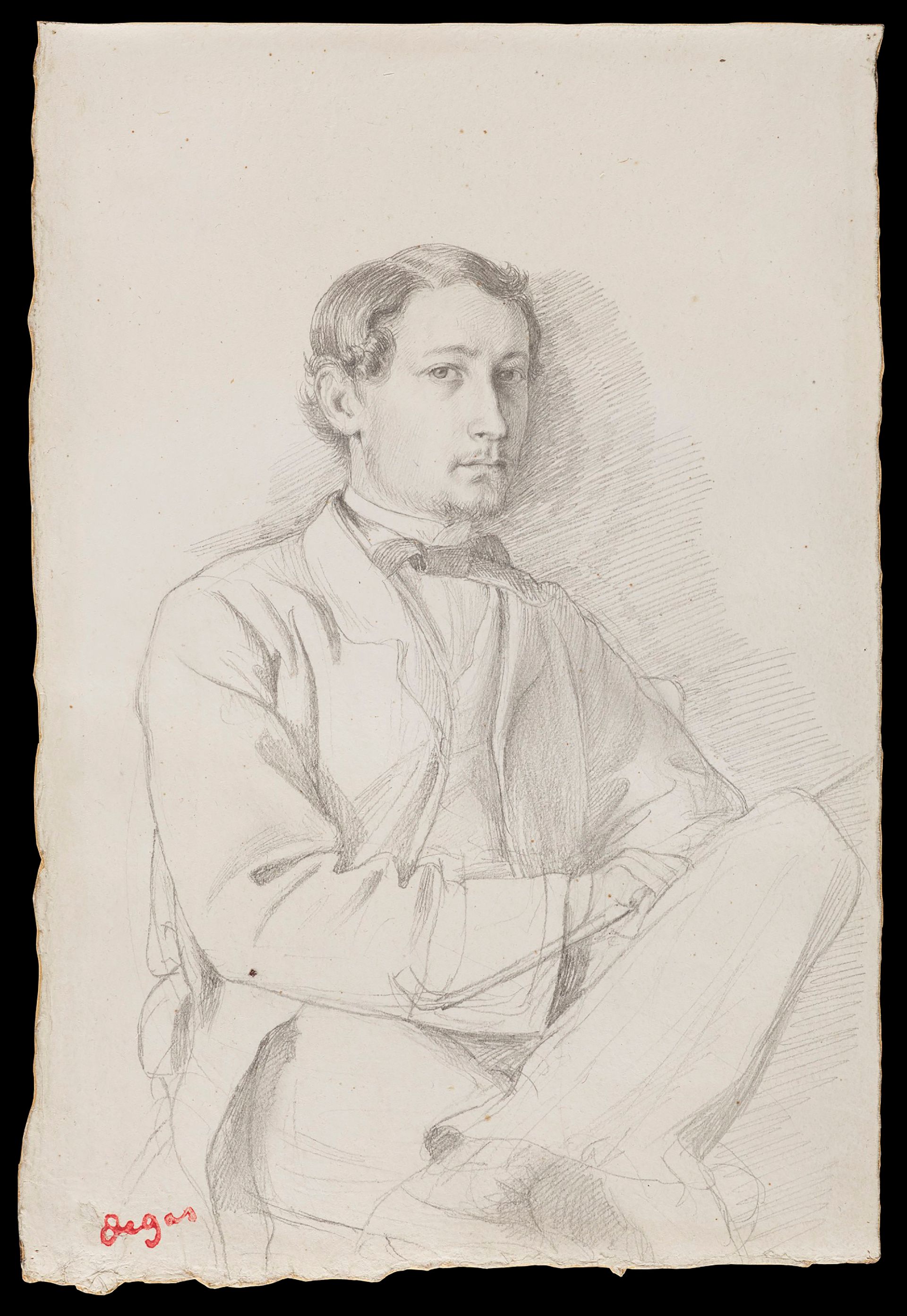

Among other highlights of the gift, the chief curator points to Degas’s “exquisite” drawing of his Neapolitan cousin Adelchi Morbilli from around 1857, the first work on paper by the artist to enter the Frick’s collection. (The museum already owns an 1879 Degas oil depicting dancers rehearsing.) The Vigée Le Brun pastel of a woman’s head, meanwhile, vitally inserts a woman into the Frick’s Old Master narrative, Salomon notes.

Edgar Degas's Adelchi Morbilli, from around 1857 Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun's Head of a Woman from 1784 Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr

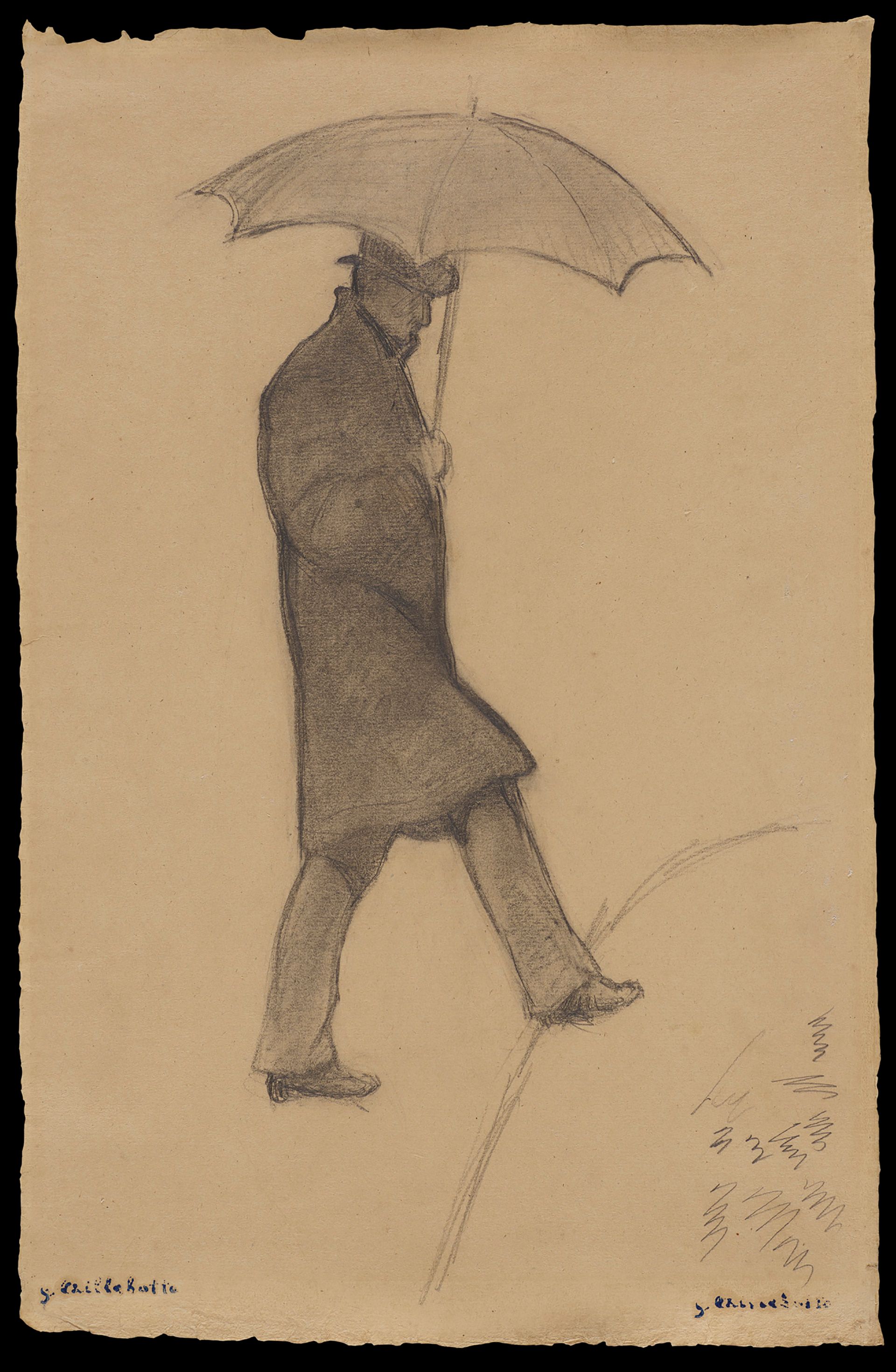

Caillebotte’s drawing of a man with an umbrella is a preparatory sketch for what is arguably his most famous painting, the 1877 urban scene Paris Street: Rainy Day at the Art Institute of Chicago. Such drawings are hard to come by, Salomon says: “Caillebotte was very wealthy and he didn’t sell a lot of works, so most of them remained with his family.”

Gustave Caillebotte's Man With an Umbrella (1877) Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr

Playing to the Frick’s strengths in French 18th-century art are works in chalk and pastel by Boucher, Fragonard, Greuze and Watteau. A 1753 pastel drawing of a shepherdess, the first pastel by Boucher to enter the collection, complements the museum’s celebrated Boucher Room, designed around eight canvases, and such well-known works as the 1753 painting of A Lady on Her Daybed. And a chalk drawing of a young woman by Fragonard from around 1770-73 dovetails with the decade in which he created the Frick’s painting cycle The Progress of Love, Salomon observes.

François Boucher's Reclining Shepherdess, from around 1753 Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr

Supplementing the four Goya paintings and sole drawing in the museum’s collection is a piquant drawing of a dancing tambourine player from around 1812-20. It originated in Goya’s “F” album of drawings of figures from everyday life in Spain, just like a drawing of fishermen that the Frick already owns, the chief curator notes.

Francisco Goya's Tambourine Player from around 1812-20 Photo: Joseph Coscia Jr

The gift also includes works on paper by Tiepolo, Delacroix, Constable, Jean-Baptiste Wicar, Jules-Alfred de Goncourt, Guido Reni, Pierre-Paul Proud’hon, Nicolas Lancret, Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, Salvator Rosa and Frederico Barocci.

Henry Clay Frick, the museum’s Gilded Age industrialist founder, “collected works on paper in a very haphazard way”, says Salomon. “He was interested in etchings by Rembrandt, pastels by Whistler.” In 2010, a bequest of 10 mostly 19th-century Romantic drawings from the former Frick director Charles Ryskamp bolstered the museum’s holdings in works on paper by nearly a third, but the quality of the donation by the Eveillards “is even higher”, the chief curator says.

Today, “our intention is not to fill every gap” in the collection “but to focus on quality, and go deeper in certain areas that are already represented”, Salomon adds. The art promised by the couple “is transformative, and adds a huge amount to our holdings”.

The museum says that the show will be accompanied by a catalogue and public programmes, and Salomon says he hopes the gift will foster research that leads to further exhibitions.