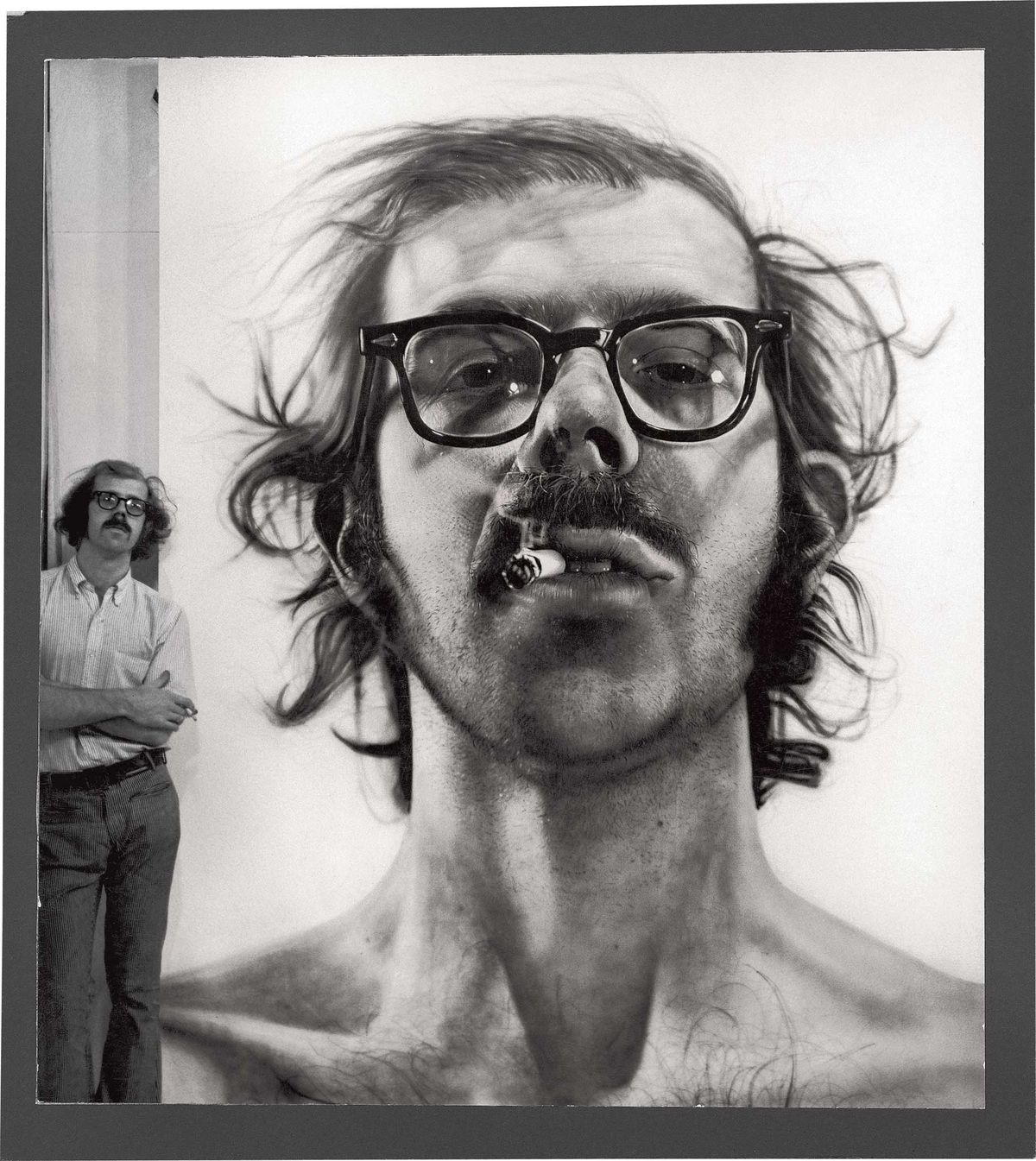

Chuck Close made portraits of monstrous size and unnerving detail at point-blank range. He died in a hospital on Long Island from congestive heart failure at the age of 81.

Close built a style and a global market with paintings and photographs of his friends and contemporaries — the composer Philip Glass, fellow artists Cindy Sherman, Mark Greenwold and Lucas Samaras — first in photo realist pictures (a description that he rejected) which brought what he called a “Brobdingnagian” look to anyone who agreed to sit for him. Gargantuan nostrils may not have been charming, but people looked at them; “Up Close” was as apt as any other description.

“I had no idea that I would still be painting heads today. Over the years, nothing interested me as much as people,” he told NPR’s Terry Gross in 2004.

Chuck Close working on the portrait Keith (1970) in his New York studio

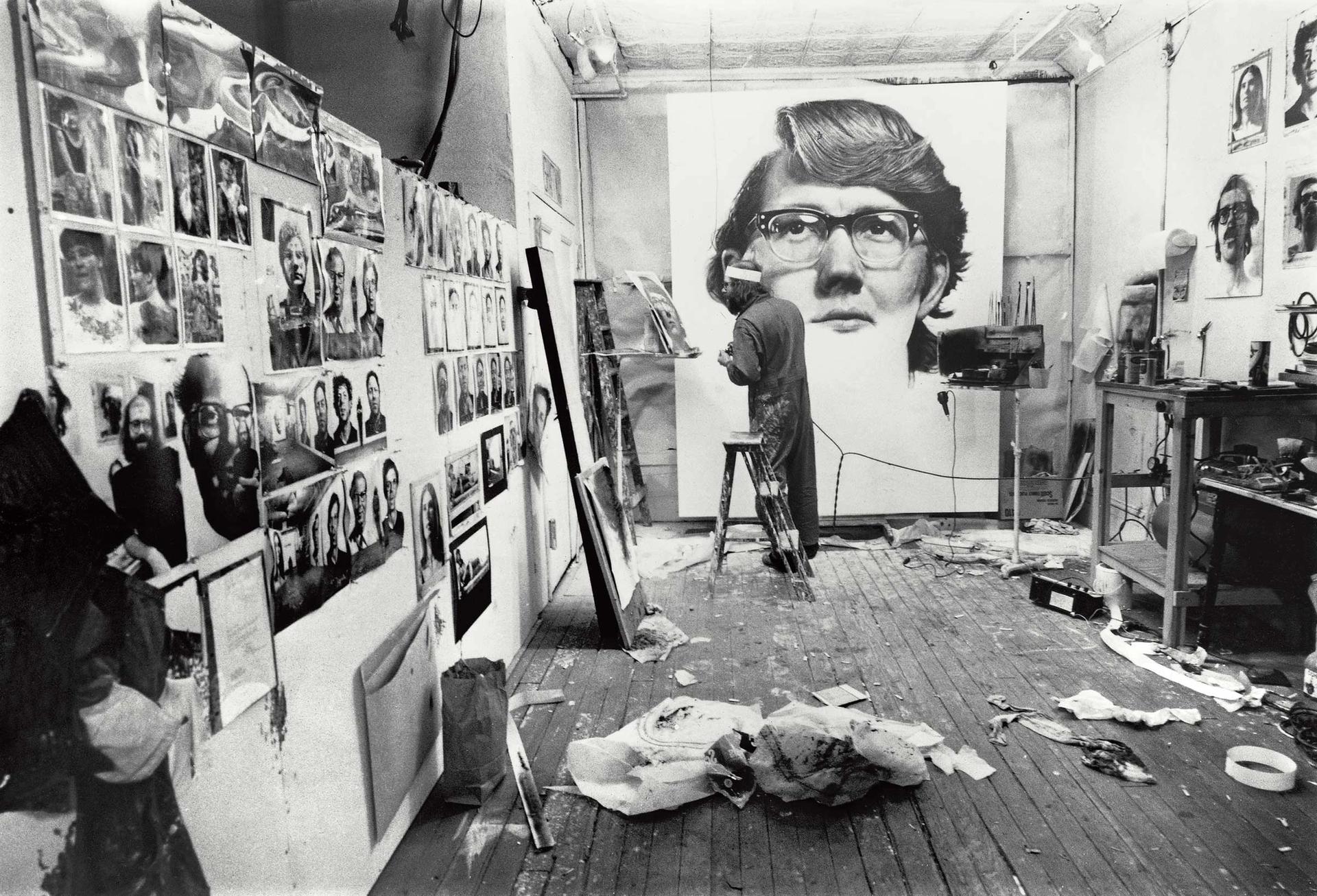

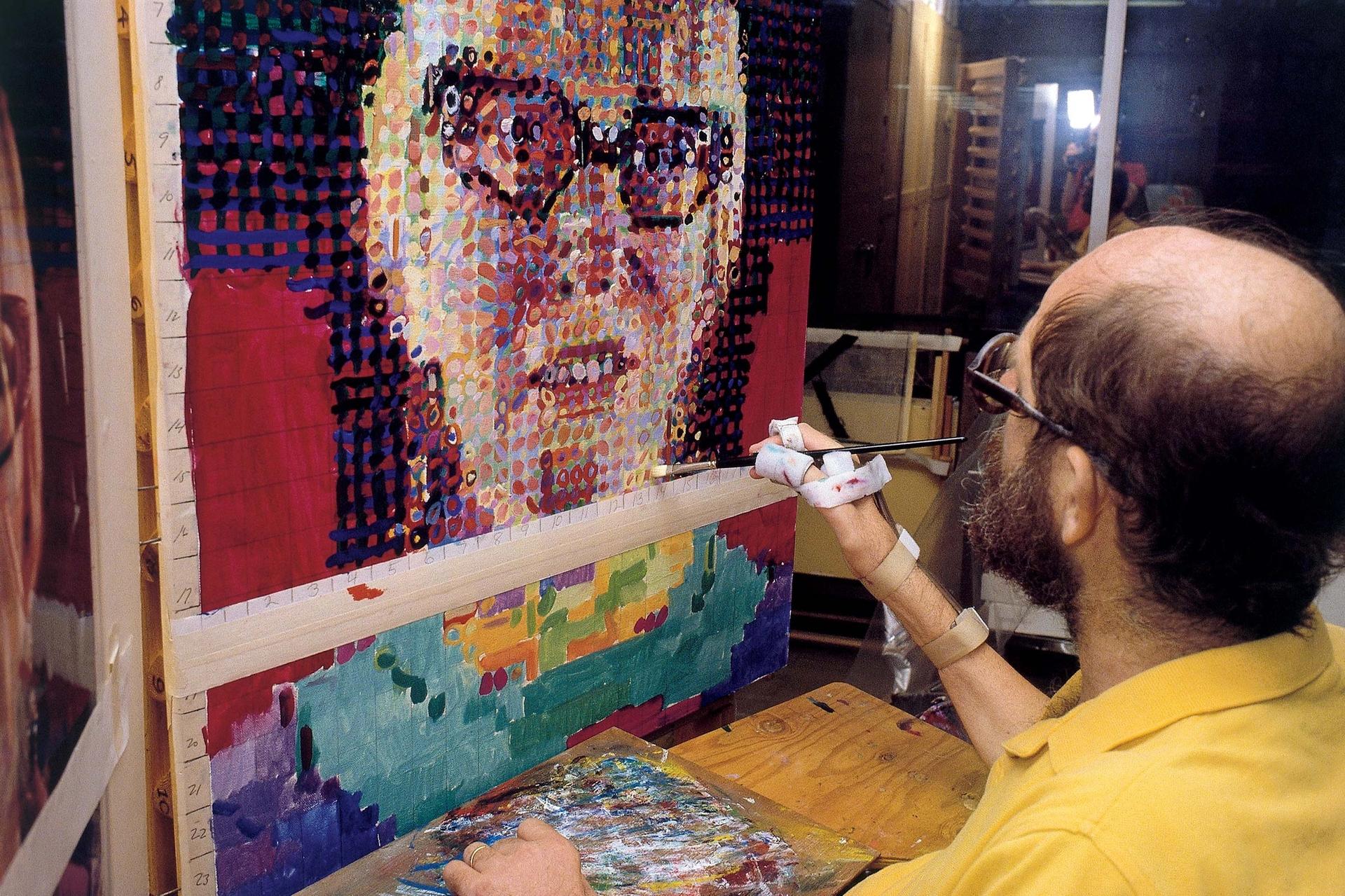

Later came an approach to painting, also on a colossal scale, in which works revealed their subjects as well as a process for constructing massive portraits with tiny irregular modules of colour and form. Close’s constitutive elements gave his work a more hard-headed feel than the pastel-shaded comic-book dots of Pop paintings by Roy Lichtenstein. If Warhol and company made portraits with a shrug, Close made them with a calculated underpinning.

More often than not, the stern-faced artist, bald and bearded before 40, was also his own subject, with an unblinking stare. His work was everywhere, from Tokyo to the Tate to the New York City subway, all the more remarkable because a stroke in 1988 left Close a quadriplegic. With intensive therapy, he was able to paint again with a brush strapped to one hand. He later moved to daguerreotypes, joking that the antiquated technique was anything but outmoded.

Chuck Close working on Janet (1989) with a paintbrush strapped to his arm

In a world obsessed with beauty and posturing, Close in his wheelchair was a regular at openings and social events in New York. In a milieu maligned for its superficiality, Close’s work, and Close, had a rare toughness.

All the more jolting, then, were the revelations in 2017 that Close had harassed women who sought to model for the daguerreotypes of his later years. Accusers said he made lewd comments after requiring them to strip naked. Some charges dated back to a decade earlier.

In a statement from 2017, the twice-divorced Close offered an apology, denials, and an explanation: “As a quadriplegic, I try to live a complete, full life to the extent possible,” he said. “But given my extreme physical limitations, I have found that utter frankness is the only way to have a personal life.”

The painter who built a following and market for portraiture disappeared from public life. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, cancelled a retrospective that was to have been a lifetime salute from “the nation’s museum”. Seattle University, in the artist’s home state of Washington, removed a Close self-portrait on display in its library.

When he died, Close, who revealed in an interview for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art that he had been diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia, was close to invisible.

A mainstay of Pace Gallery, which still lists him among its artists, Close was born in Monroe, Washington in 1940. His mother was a pianist, his father a plumber who died young. A lackluster student with dyslexia, he was better at art than anything else. “Everything in my life is a product of my learning disabilities,” he said. Close made it through college and then to Yale, where Richard Serra, Brice Marden, Jennifer Bartlett and Robert Mangold were classmates. He then taught at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, before moving to New York in 1967. The Walker Art Center gave him his first retrospective in 1979. The Whitney followed in 1981, MoMA in 1998.

Chuck Close working on Self-Portriat (2000-2001)

In an interview with The Art Newspaper before his 1998 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (originally planned for the Metropolitan Museum of Art), Close reflected on finding his way and refining his approach to portraiture:

“I’ve done a number of things to isolate myself from the buffeting winds of change in the art world. By having my own odd eccentric path to follow, the cataclysmic sea changes didn’t affect me very much, but I did feel the need to reconnect myself with what I do by trying to re-establish urgency. I always thought that problem-solving was greatly overrated, that the most important thing was problem-creation, how do you put yourself in an interesting position by asking yourself a question that no one else is asking, and because no one else’s solutions are applicable, you’re more likely to arrive at a personal solution. If you accept the problem of the moment, your solution is very likely going to be ordinary. That’s how I got into portraiture in the first place…

In 1967, painting was dead, yet again. It’s been dead so many times in my career I can’t believe it. But of course, I think that the times when painting is dead are absolutely the best times to make paintings…

As the Japanese say, be poised for the recovery. You don’t want to jump on the bandwagon after everyone else realises that this is the thing to be doing. Figuration was totally out of the question. Sculpture ruled in the late 1960s. And I remember Clement Greenberg said that of all the things that couldn’t be done in art any more, the portrait was at the top of the list. And I guess that’s what got to me; the fact of someone declaring something so bankrupt, so hopelessly lost, so pathetically out of it, that only a fool would attempt to breathe new life into it. That must have appealed to me. I thought that Greenberg was a horrible influence on art, although I remain a dyed-in-the-wool formalist.”

The debate over Close’s place in post-1970 art history, quiet since allegations against him were made, is sure to gather steam with his death. And Close has not disappeared altogether. A show of Close’s works at the Gary Tatintsian Gallery in Moscow (with the cooperation of Pace Gallery) runs through 25 September.

• Photos from ChuckClose.com