Kenny Scharf is a survivor. Scharf, whose smiley blobs and television creatures were his signature on the 1980s graffiti scene in New York, survived the HIV/Aids crisis that killed his friend and fellow street artist Keith Haring in 1990. Another pal, Jean-Michel Basquiat, who scrawled his SAMO tag all over Lower Manhattan before colliding with dealers and collectors and the glittery drug scene, died of an overdose in 1988.

Scharf also survived the decline of the East Village galleries that had brought him into stardom. As dealers took graffiti from the street into galleries, and those spaces then closed or moved, he and other 1980s art stars were eclipsed like anything else that slips out of fashion.

Kenny Scharf: When Worlds Collide, oozing with images that will please his fans, joins Scharf, now 62, as he assembles scavenged trash into sculptures and décor in sunny Los Angeles, where he was born.

The film rewinds to revisit the early New York days when Scharf and Haring shared a loft and art-buying soared until Wall Street crashed in 1987. Basquiat, a friend until they fell out, cannot remember details in a clip of archival video. Scharf and his fellow artists talk of a close yet fiercely competitive community sustained by cheap rents, youth, drugs and fun—“the f-word,” one of them called it. Aids—“our Vietnam, our hydrogen bomb,” in the words of actor and performance artist Ann Magnuson—soon took its toll. Scharf fled New York and traded his pictures to pay his bills in Miami, which was anything but art territory in 1992. He remembers someone saying, “Oh, Kenny Scharf, I thought you were dead.”

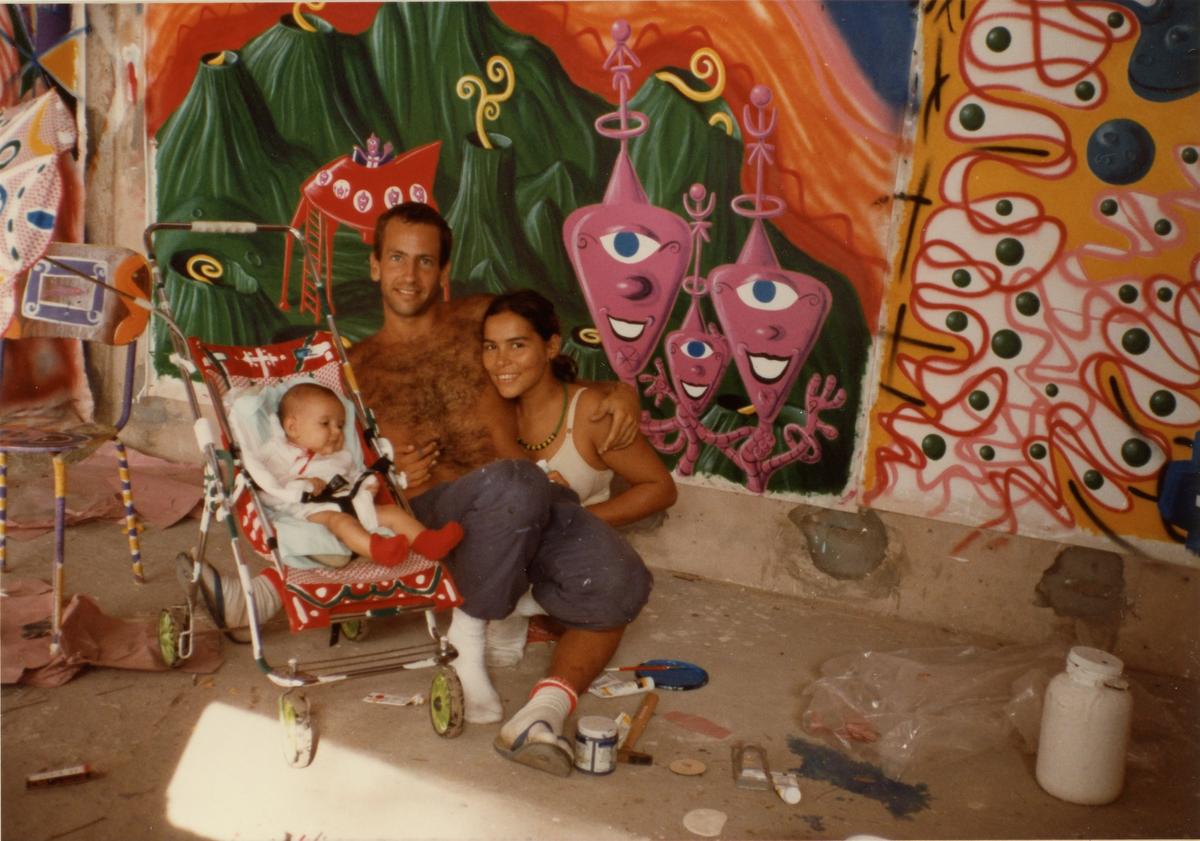

Those ups and downs (mostly ups) are viewed with affection in the film co-directed by his daughter Malia Scharf and Max Basch. The affable Scharf was also lucky. On a trip to Brazil in the 1980s, he met Tereza, the woman who would become his wife, and bought a beach house where Haring would visit. The East Village spray painter with a kid’s nickname became a father. Scenes with his wife and two daughters are the film’s most tender moments.

Art bio-docs, especially of living artists, tend to be celebratory rather than critical, and this one fits the template. As Scharf talks about his inspiration—“I’m in love with nature, and I’m embracing the beauty of nature and the beauty of painting. Nature is God, I guess”—the artist-admirers Marilyn Minter, Ed Ruscha and Yoko Ono echo their approval.

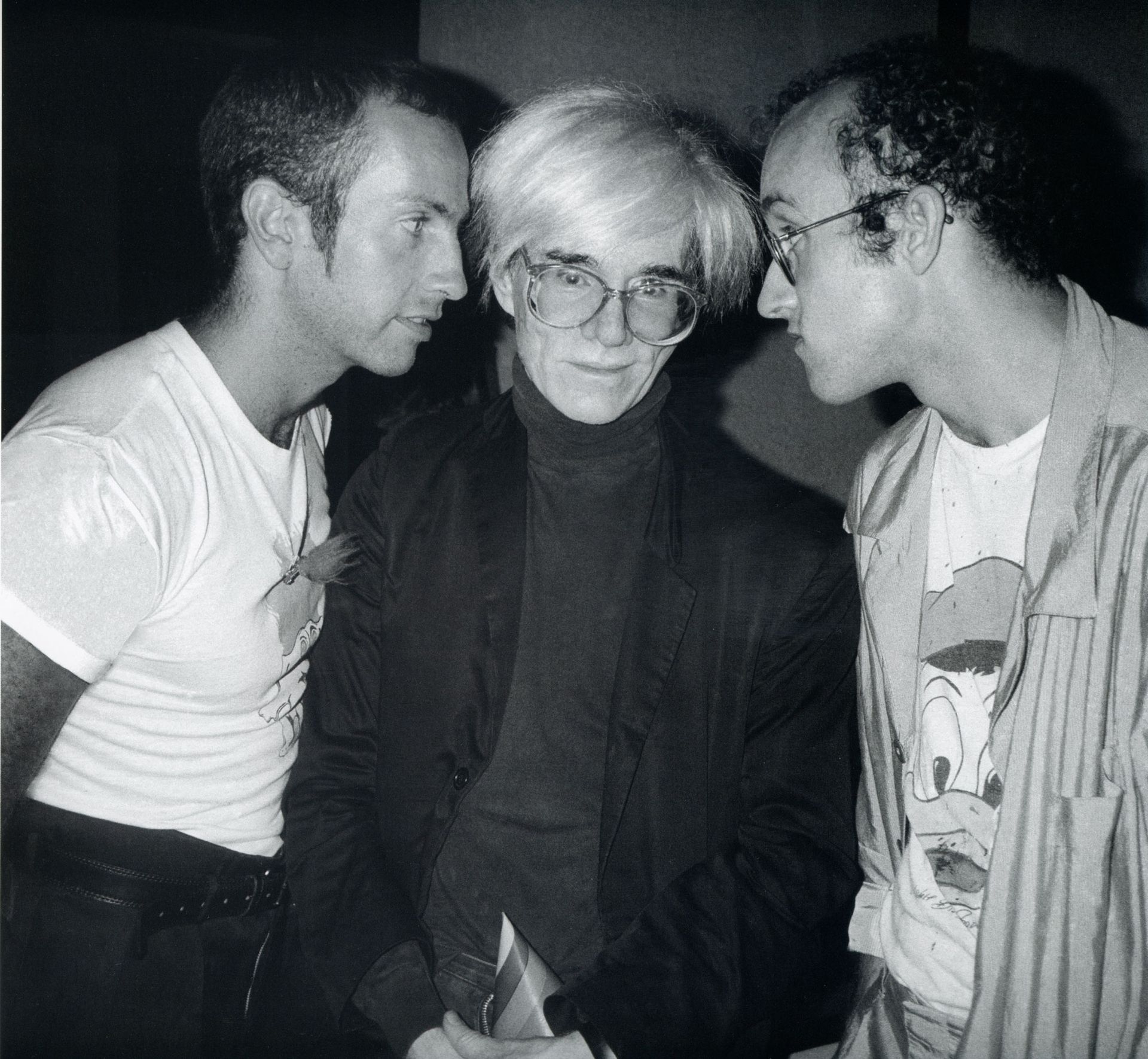

Kenny Scharf (left) with fellow artists Andy Warhol and Keith Haring in 1987 as seen in Kenny Scharf: When Worlds Collide, directed by Malia Scharf and Max Basch. A Greenwich Entertainment release Photo: Patrick McMullan

Scharf’s timing in the 1980s was right. The novelty of graffiti enabled Scharf to give cartoon images a new and profitable life as art, while the comics artists at publications such as Heavy Metal and Raw, who created characters with similar bulbous eyes and slimy limbs, toiled away in isolation for next to nothing.

The film is not clear on how Scharf found his way back into vogue after years under the radar, but he is now making the same sprayed and painted pop-inspired faces, with doses of nature, plus assemblages of found objects. And the work sells on several continents. After all that time, the Kenny Scharf brand still has value.

With all the talk of his “cartoony” art being fun, Scharf himself wonders about his own childishness, a “Peter Pan” side wary of maturing. He is right to wonder. While Haring and Basquiat, who died decades ago, have legacies, Scharf the survivor is still working on one.