For football fans, April 2021 will always be remembered as the moment when those who eat at the top table of European sport tried, but failed, to run off with the dining table.

The European Super League was an attempt by 12 of the biggest clubs in England, Italy and Spain to form a lucrative break-away competition that would eventually allow 20 elite teams to play regularly among themselves in front of a multibillion-dollar TV audience without fear of being knocked out or relegated.

This vision of limitless revenue streaming collapsed after large numbers of supporters of the would-be founder clubs, particularly English teams such as Chelsea, Arsenal, Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur, mounted impassioned protests outside the gates of their grounds. Within 72 hours of the Super League’s plans emerging, eight out of the 12 clubs withdrew and the project was abandoned.

What has this got to do with the art world? Quite a lot, actually. In recent years the world’s most valuable football clubs and works of art have both become targets for super-wealthy investors who, for whatever reasons, want to spend huge sums of money on prestigious names.

Chelsea and Tottenham are respectively owned by Roman Abramovich and Joe Lewis, both billionaire art collectors. Last year, the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, the end buyer of Leonardo’s $450m Salvator Mundi, made an unsuccessful attempt to buy Newcastle United for £300m. The seller of the Salvator Mundi, Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev, is president and owner of the French Ligue 1 team, AS Monaco.

And so it goes on. Money makes the multibillion businesses of art and sport go round. But the European Super League fiasco troubled the minds of millions of football lovers, making them question the hold that the super-wealthy have on the “beautiful game” in a way that rarely discomposes the international art world.

Fans of Newcastle (which finished 12th in the Premier League this season) would have understandably welcomed Middle Eastern cash to buy trophy-winning players. But the fact remains that when confronted with a project as financially cynical as the European Super League, this same type of supporter was outraged enough to man the turnstiles and stop what Ander Herrera, a Spanish midfielder who plays for Paris Saint-Germain, described as “the rich stealing what the people created”.

Radicalism for sale

What the European Super League was trying to do was turn the game of football into a commodity, something that capitalism achieved long ago with art.

“One of the lessons of modernism was that art could be radical, aesthetically and politically,” says the sculptor Anish Kapoor. “Postmodernism, however, sees artists as makers of luxury goods for the rich. How can the radical have a radical voice when it is for sale? It is just more commodity. We artists have to change this. I don’t see it coming. So the commodity goes to those who will pay the most.”

Compared to football, the art business is small. It has far fewer participants and doesn’t have a global mass fanbase. But the huge prices paid by the wealthy for trophy works by star artists do parallel the millions top clubs pay to secure the skills of the world’s most talented players. Jeff Koons moving from Gagosian and David Zwirner to Pace might not be as newsworthy as current rumours of Cristiano Ronaldo wanting to leave Juventus for Manchester United, but similar power structures prevail. The actions of top football clubs—like those of the top galleries, auction houses and art fair organisers—tend to be determined by billionaires, private equity vehicles or sovereign wealth funds.

These structures present a continuing challenge for artists who regard themselves as politically aware or engaged.

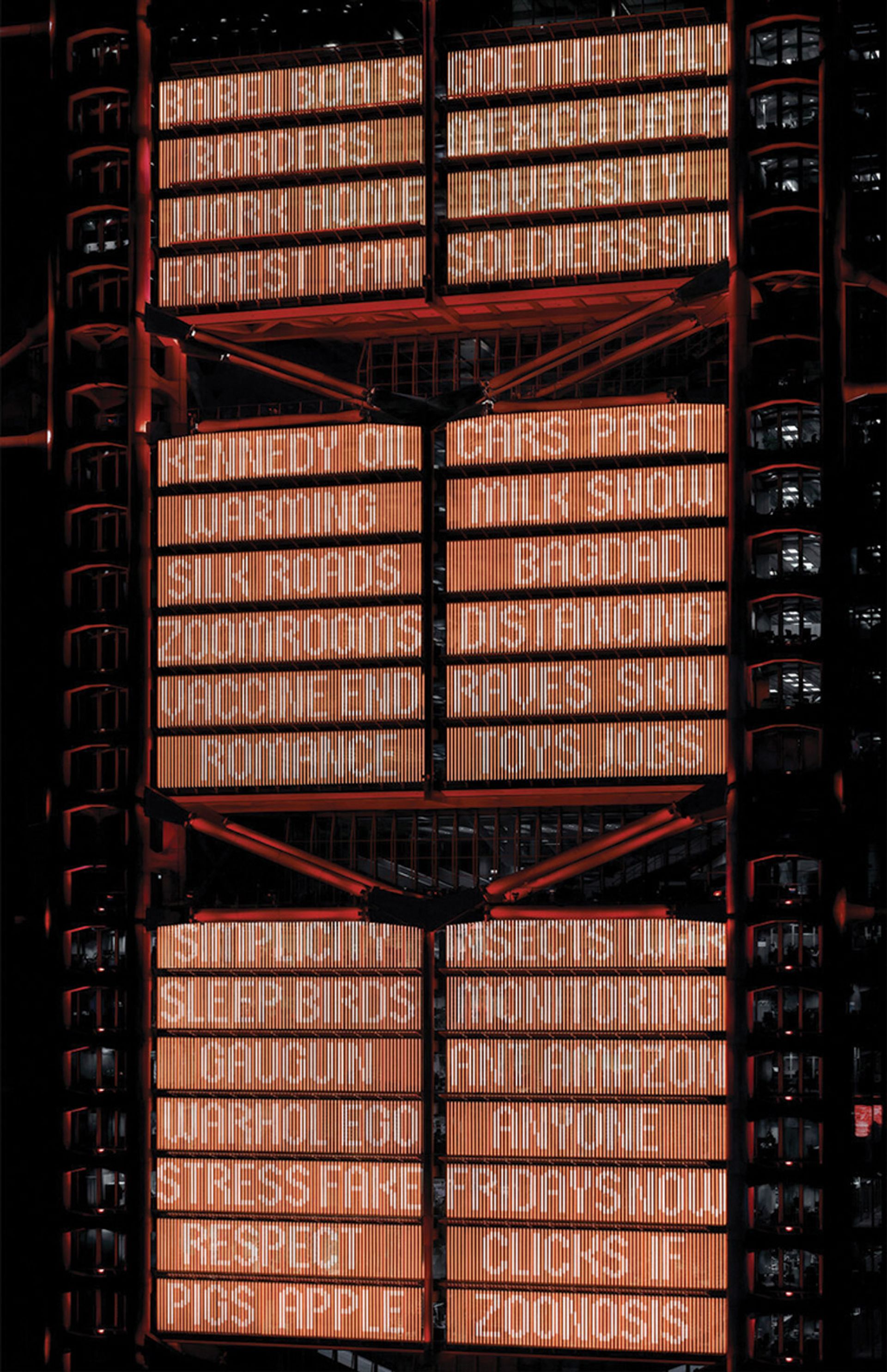

Reflecting on power structures: Andreas Gursky’s monumental photograph Hong Kong Shanghai Bank III (2020), shown at Art Basel in Hong Kong in March © Andreas Gursky. White Cube

In March, the Swiss-based MCH Group—now majority owned by James Murdoch’s private investment firm Lupa Systems—held a Covid-adapted edition of its Art Basel fair in Hong Kong, whose democratic autonomy has been all but crushed by the Chinese government.

The London gallery White Cube, which also has a branch in Hong Kong, was among the 104 exhibitors. Among its offerings was the monumental Andreas Gursky work Hong Kong Shanghai Bank III (2020), showing the Norman Foster-designed HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong, illuminated with words such as “Monitoring” and “Borders”. According to White Cube these “invite the viewer to reflect on the power structures that filter and direct all interpretations of historical events”.

Art and politics

If this work, priced at €400,000, was a critique of a superpower whose persecution of its minority Uyghur people has been described by the US and UK governments as genocide, then that critique was very oblique indeed. Conversely, could the presence of a Western art fair at the state-owned Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre be viewed as an endorsement of that very same regime? At the time of writing, Art Basel said that it was “not aware of any criticism of this kind”.

“There are two ways to look at Art Basel in Hong Kong,” says Joes Segal, the chief curator at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles and author of the 2016 book Art and Politics: Between Purity and Propaganda. Segal thinks the fair can be viewed as “a manifestation of the art establishment offering legitimacy to a suppressive regime”, or, alternatively, as a “breeze of fresh air in terms of creativity and political engagement”. He adds that the downside of cancelling such international events is that “it takes away the opportunity for people in places like Hong Kong to stay in touch with the outside world and feel supported”.

There are, of course, plenty of recent examples of artists standing up and being counted over a political or social issue. Ai Weiwei has for years been an outspoken critic of China’s authoritarian regime. Nan Goldin has tirelessly exposed how members of the Sackler family used profits from sales of its fatally addictive opioids to fund philanthropic art projects. Banksy has used the profits from his sales to buy a rescue boat for migrants in the Mediterranean.

But right now, after the wake-up call of the Black Lives Matter movement, it is identity politics, rather than politics, that dominates the West’s contemporary art culture, commercially and institutionally.

Works by female artists concerned with issues of identity and race drew intensive bidding last month at Christie’s 21st Century evening sale in New York. Paintings by Jordan Casteel ($687,500), Nina Chanel Abney ($990,000), Lynette Yiadom-Boakye ($1.95m) and Mickalene Thomas ($1.8m) all set record prices.

Robert Colescott’s 1975 satirical masterwork George Washington Carver Crossing the Delaware, wittily recasting a pivotal moment in American history with African Americans, was the $15.3m star of Sotheby’s equivalent auction of contemporary art.

Identity-based art has become a highly lucrative commodity for the top auction houses, driving price growth at remote live-streamed auctions that are less entertaining than the umpteenth rematch between, say, Manchester United and Juventus in the would-be European Super League.

Sotheby’s and Manchester United are both owned by private equity investors—respectively Patrick Drahi and the Glazer family—who relied on huge quantities of debt to finance their leveraged buyouts. United fans continue to mount protests against the club’s disengaged, growth-obsessed American owners, recently forcing the postponement of a match against Liverpool.

Meanwhile, Drahi, who bought Sotheby’s for $3.7bn in 2019 using $1.1bn of debt, plans to sell a further $300m of debt to finance a dividend payout to the company’s owners, primarily himself, according to the Financial Times (FT). In 2020, wage reductions and redundancies saved Sotheby’s $98m, enabling it to report a $39.1m profit, the FT reports.

This kind of aggressive cost-cutting and cash-extraction is the sort of ownership strategy that would enrage football fans, but in the art business it is simply regarded as the way of the financial world.

“In democracies, art is all about creative freedom, but unfortunately this includes the freedom of the public not to understand and not to care,” Segal says.

That’s the point. The art world might pride itself on its political awareness, but unlike football, not enough people care about art for questions to be asked about the power structures that control this particular game.