“Hannah Wilke was a provocateur—a certain notoriety followed her and she also cultivated it,” says Tamara Schenkenberg, the curator of an exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St Louis dedicated to the pioneering feminist artist who used the taboo subject and form of the vagina as her central motif. “She’s an interesting figure, both well-known and influential, but also understudied.”

The exhibition Hannah Wilke: Art for Life's Sake (4 June- 16 January 2022) features nearly 120 works spanning three decades, from the artist’s early suggestive boxlike vessels in clay made in the early 1960s while a student studying sculpture at the Stella Elkins Tyler School of Fine Arts near Philadelphia, to her more overtly vulvic shapes layered or folded by hand in clay, latex, kneaded eraser or chewed gum—and sometimes incorporated into her photographs and videos of herself performing disrobed in the 1970s. It also includes Wilke's photographs documenting her mother’s cancer and then the ravages on her own body from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, from which she died in 1993 at age 52.

Hannah Wilke, Five Androgynous and Vaginal Sculptures (1960-61), terracotta Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Courtesy Alison Jacques, London. © 2021 Scharlatt Family, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

As with her contemporaries, Carolee Schneemann and Lynda Benglis, who also used their own nudity in their work to question gender stereotypes and assert sexual liberation, Wilke experienced a backlash from some feminist peers for works such as S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974), consisting of 28 photographs in which she appropriated glamorous poses from magazines and advertising, and affixed small chewing gum labia shapes in patterns across her face and naked torso. The art critic Lucy Lippard, in a 1976 essay in Art in America, attacked Wilke for “her own confusion of her roles as beautiful woman and artist, as flirt and feminist”.

“I think now we understand you can be both,” says Schenkenberg, who feels that Wilke’s message of self-love, body positivity and women’s agency is very resonant with younger audiences today. The curator is interested in how the gum sculptures disrupt the viewer’s gaze in the S.O.S. works. “You could read those patterns as Morse code, or as signs of damage that society puts on women to perform in this way,” she says. “They're pleasure centers too because they're vaginal forms and also works of art that interrupt the conformity into which women are boxed. It's not surprising that people thought this work was politically ambiguous.”

Hannah Wilke, S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974), lifetime silver gelatin print Collection of Michael and Sharon Young, courtesy of Alison Jacques, London. © 2021 Scharlatt Family, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Not afraid to call out certain feminists for what she felt were double standards and biases about how women should use their bodies, Wilke made a poster in 1977 using the text “Marxism and Art” and “Beware of Fascist Feminism” with an image of herself topless staring down the viewer tauntingly.

A previously unpublished 1975 conversation between the art critic Cindy Nemser and Wilke is one of only a few interviews with the artist to have survived and is reproduced in the exhibition catalogue. In it, Wilke commented, “Eros has to do with affirming life,” an expansive idea that helped inform the exhibition, according to the curator. “Eros for Wilke was not just a libido or a sexual drive but it was a drive for life, for love, for pleasure, for self-fulfillment,” says Schenkenberg. “She tells us exactly where to locate this drive for life in her work which is movement, this pushing and pulling, the opening up and closing.” Schenkenberg has tried to trace that across three decades of Wilke's work.

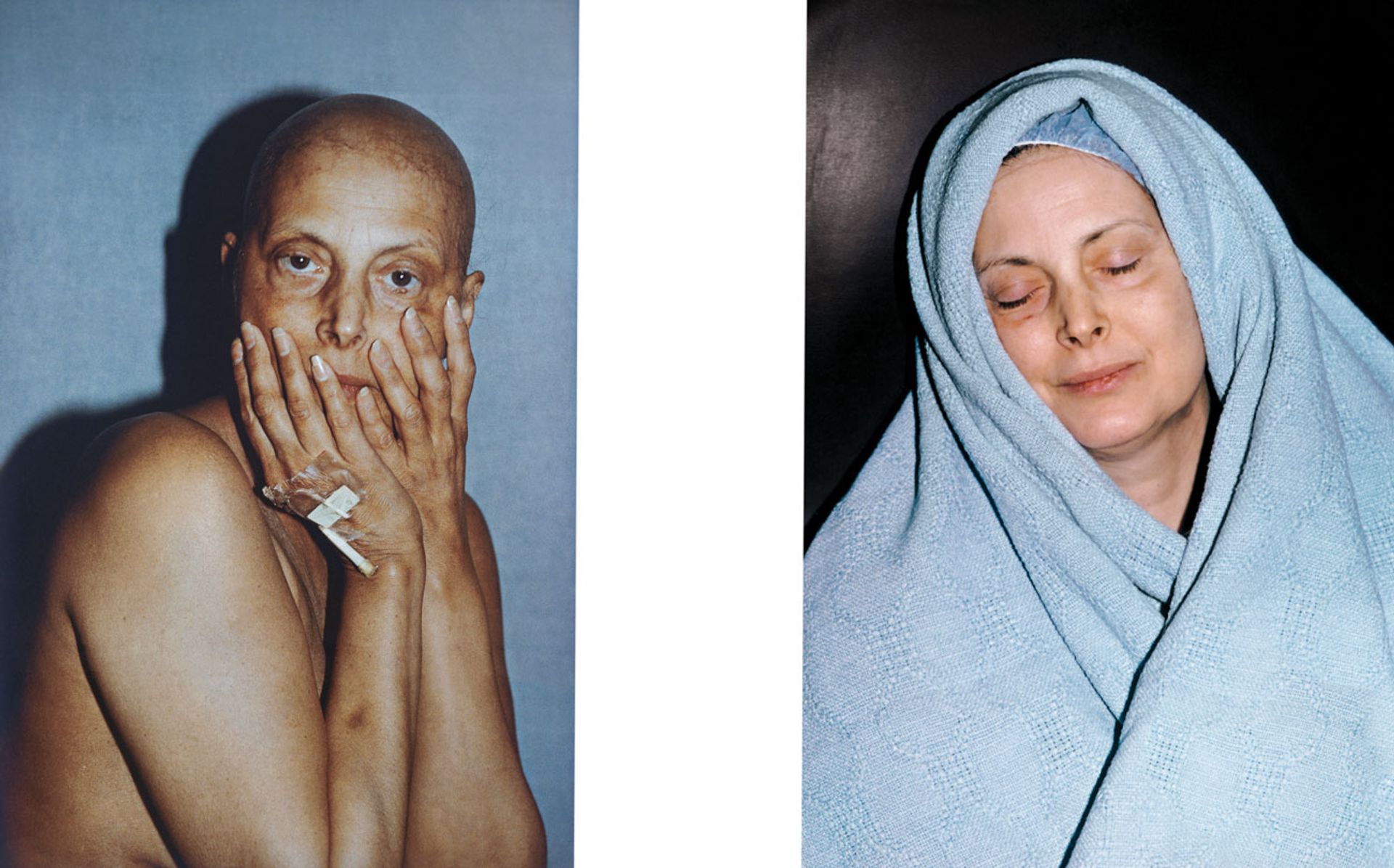

Hannah Wilke, Intra-Venus Series No. 4, July 26 and February 19, 1992 (1992) Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles, courtesy Alison Jacques, London

In her final Intra-Venus Series (1991-93), which is startling to look at, Wilke adopted coquettish and art-historical poses with her naked body, bandaged and battered from cancer treatment. “If you think about S.O.S., those gums act as scars, and in these later works there are literal scars,” Schenkenberg says. “There’s tragedy and humour and vulnerability because she’s depicting herself in this unsparing detail. I think she’s affirming the life of the body, even if that body is compromised.”

• Hannah Wilke: Art for Life’s Sake, Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St. Louis, 4 June-16 January 2022