A few hundred metres from the residential tower destroyed by an IDF bomb in Gaza City on Tuesday, a new art school is literally picking up the pieces. Students at the Dar al Kalima Training Centre, housed in a refurbished mid-century house with a courtyard garden, are collecting broken glass to make stained glass art in the shape of doves.

While it is still not safe enough to return to the school, the only accredited fine arts academy in Gaza, its founder Mitri Raheb, a Lutheran priest from Bethlehem says: “We have to continue making art, it’s very important. We can’t let destruction have the last word.”

The art school began as a satellite programme to Dar al Kalima College, an institution founded in Bethlehem by Raheb in 1995, in an old Ottoman-era building that was restored and converted from a former church crypt.

“I went for a visit in 2018,” Raheb recounts from his home in Bethlehem, “and after I left, 200 young Gazan artists had befriended me on Facebook. Everyone asked me to start an art college in Gaza.”

By 2019, the Dar al Kalima satellite programme had begun in a corner of Gaza’s French Cultural Centre and soon, an old house in the centre of Gaza was acquired and refurbished with the help of students, volunteers and funding from Bright Stars of Bethlehem, a Chicago-based NGO that assists both colleges.

Soon offices and studios were built, and the school opened on 7 March 2020—just in time for the global pandemic. Still, classes continued even as new variants ravaged Gaza’s fragile health care system and crowded refugee camps. Over the past year, many workshops and exhibitions of photography, videography, painting, and sculpture have taken place, as well as concerts and radio broadcasts of traditional and popular Palestinian music.

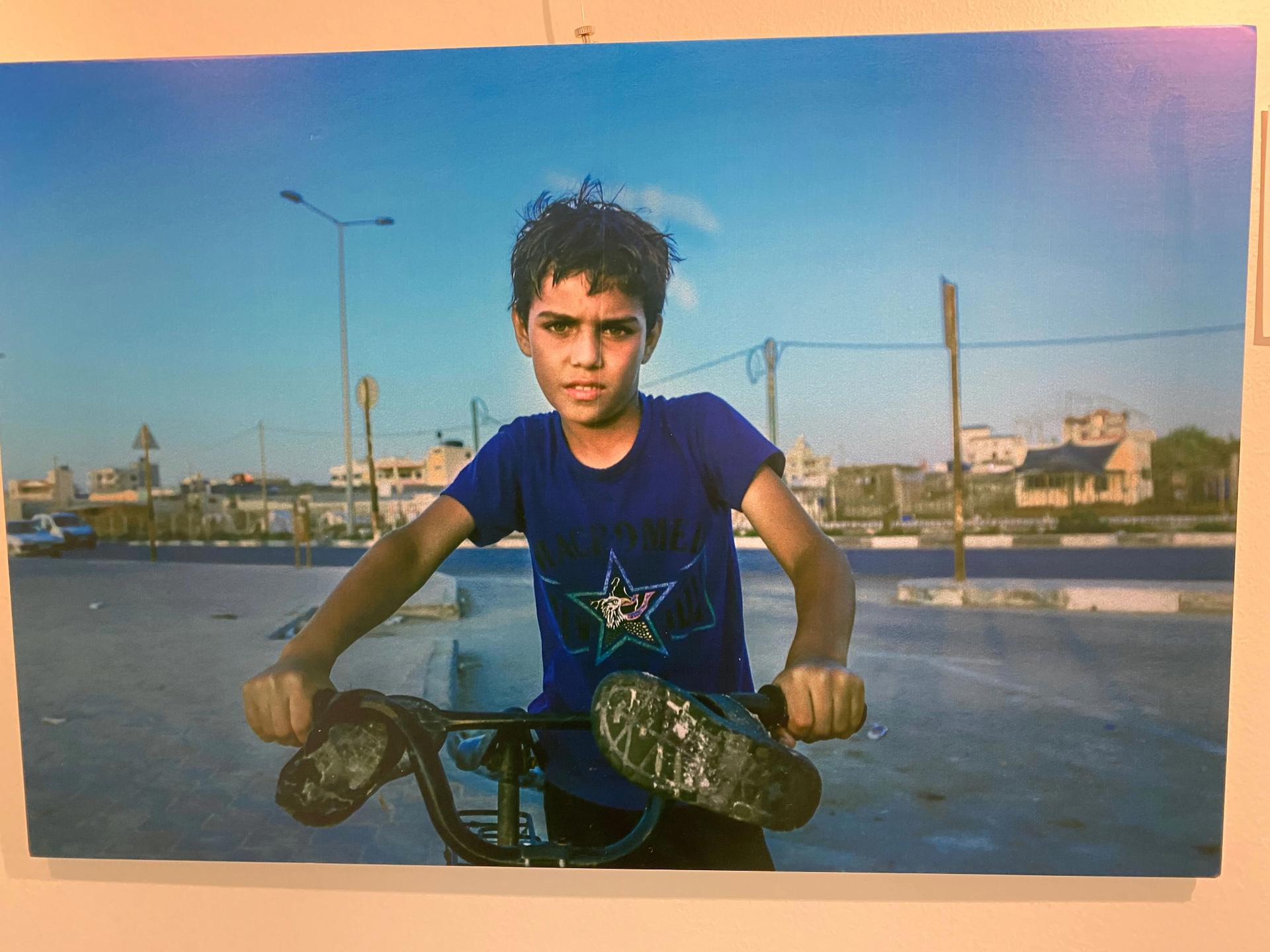

A photograph by a student, Humam Alnazali, from an exhibition entitled Childhood and Misery

The aerial bombing has halted classes for now, but plans are in the works for a new programme, based on one initiated by Raheb in Beirut last August, to showcase the work of young artists and sell their work internationally.

While getting anything in and out of Gaza is challenging, due to a blockade by land, sea and air imposed by Israel and Egypt since the fundamentalist organisation Hamas took over the government in 2007, there are ways and means to get art out of the Gaza Strip into the West Bank. “Wood-carvings are not allowed,” notes Raheb, “but paintings, embroidery and some traditional textile arts are ok.”

The college is still fundraising to subsidise tuition fees for Gazan students, who in turn run community-based workshops, often in refugee camps, for younger children.

Raheb pauses for a moment to check a message on his phone from one of the college staff about another bomb that has fallen near the school. “I believe that diamonds are made under pressure,” he says. “There is so much pressure now in Gaza, but there are so many diamonds.”