Provenance research is “undoubtedly the main question museums have to deal with in the coming years to maintain their credibility”, says the Musée du Louvre’s director, Jean-Luc Martinez. The museum has now put a catalogue of almost all of its collections online, gathering together around 485,000 object records drawn from dozens of internal databases. Previously, members of the public only had access to listings for around 30,000 works exhibited in the galleries.

More than 1,700 works that were recovered in Germany after the Second World War but have never been returned to the descendants of their rightful owners are listed under the category of Musées Nationaux Récupération (MNR). The works do not belong to the French state but are managed by the Louvre and entrusted to French national museums for safekeeping. The new collection website says the Louvre “is committed to carrying out research to find their rightful owners or beneficiaries”. In late 2017, the museum opened two galleries of MNR paintings to encourage heirs to come forward.

In addition, the Louvre has so far checked some two-thirds of the 13,943 works it acquired between 1933 and 1945 for problematic provenance, Martinez said during a preliminary appraisal of the research earlier this month. He anticipates that the museum will add the findings from this initiative to the new digital collection catalogue at a future date. The website “is evolving and putting it online is only a first step”, he tells The Art Newspaper.

The director, who is seeking a new three-year mandate after his current contract expires in April, insists that due diligence be extended to works acquired up to the present, as several French museums have been caught in bitter legal battles over looted art purchased decades after the Second World War.

In January 2020, Martinez appointed the scholar Emmanuelle Polack to lead the Louvre’s provenance research, a first for a French museum. France has been regularly accused of dragging its feet in the restitution of Nazi-era looted art. Polack began by providing the museum’s curators with copies of the 22 July 1941 French law ordering the “aryanisation” of any company owned or led by Jews, including the main Parisian art galleries.

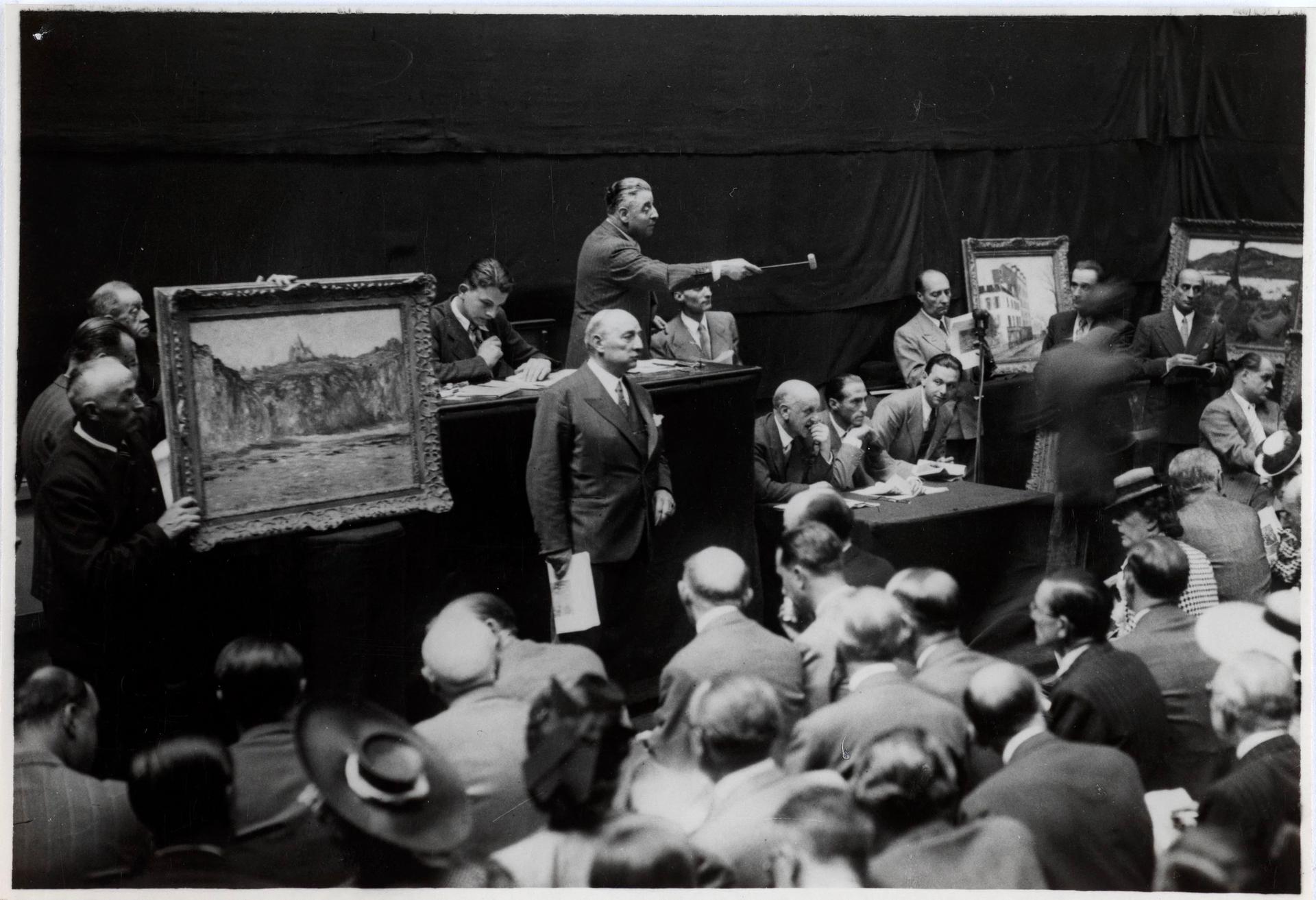

An auction of important Modern pictures at Hôtel Drouot in Paris on 5 June 1942 © Roger-Viollet

Many curators were apprehensive and feared a Pandora’s box was being opened. After all, the Louvre continued shopping on the capital’s flourishing art market under the Nazi occupation. In the wake of the liberation of Paris, the museum even held an exhibition entitled New acquisitions, 1940-1945. After a fierce resistance, the museum was condemned in 1999 to restitute looted paintings that were recovered in Germany, including a Tiepolo which is now at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Today, the Louvre is facing another claim on purchases from the dispersal of Armand Isaac Dorville’s collection in Nice in 1942. Several works from the sale have already been restituted to Dorville’s heirs: in January 2020, the German culture ministry returned three works that were acquired by Hitler’s art dealer, Hildebrand Gurlitt.

In a meeting on 10 March, all the Louvre department heads expressed their relief that very few cases of potentially looted art had actually been found. Some staff members still seemed reluctant to admit that works found on the French market at the time could have come from persecuted Jewish families. Several called for international co-operation, especially with the British Museum, on cases such as the Pringsheim collection sale in 1939 at Sotheby's in London, forced by the Nazis, and where several museums acquired important majolica.

Martinez has asked curators to conduct the same investigation for works from former colonies. He says he has been struck during trips abroad by the number of times the Louvre was accused of relying on looted collections, which, he insists, is “only very marginally true”.

France’s Asian collections were transferred in 1945 to the Musée Guimet and those from Africa or Oceania are held at the Musée du Quai Branly, so the Louvre’s colonial provenance research is mostly focused on Roman sculpture and objects from Algeria as well as Tunisia, Syria and Lebanon. The Louvre is also planning exhibitions on archaeological finds from these former colonies or protectorates.

The museum intends to examine the provenance of objects from other European empires. “Our collections are mostly archaeological and come from digs shared with the countries of origin. Clearly museums like the Louvre served imperial ambitions and we have to deal with this history and our confrontation with the Ottoman empire. But these acquisitions, covered by bilateral agreements, were legal. We have to explain this to a wider audience,” Martinez says.