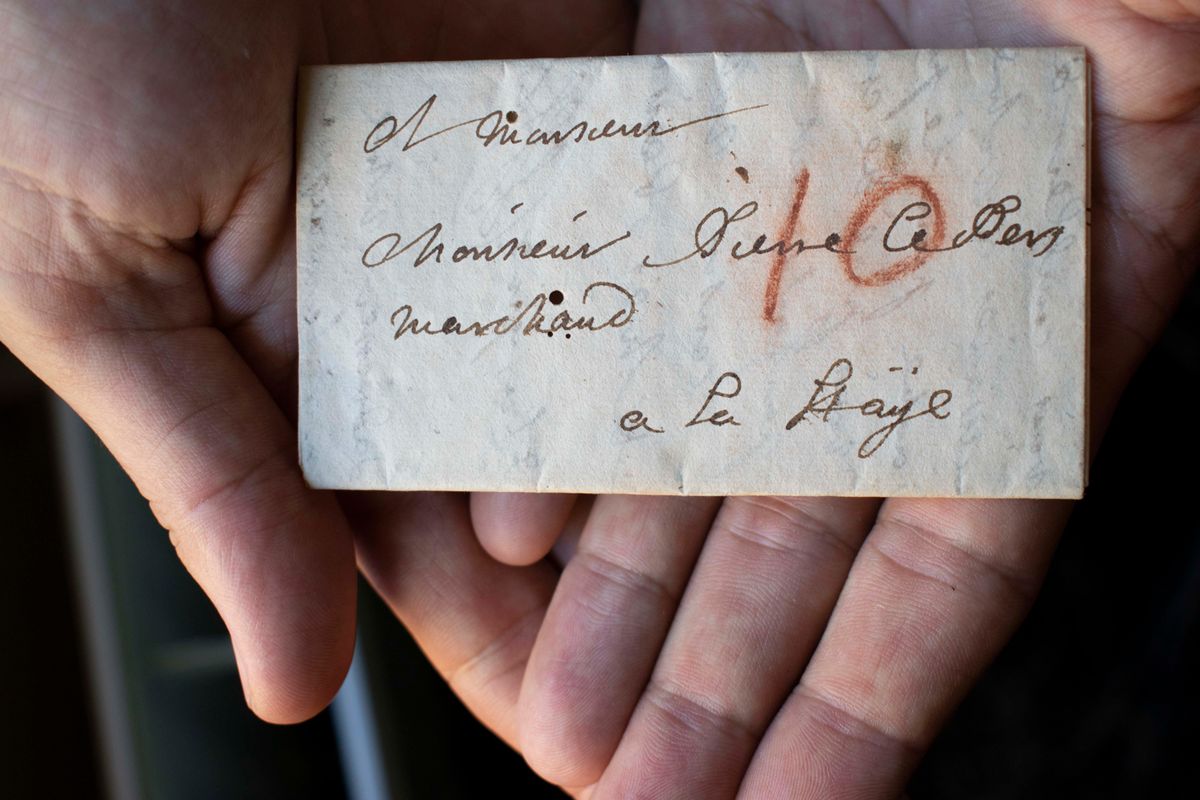

A letter posted more than 300 years ago from Paris to the Hague, but never delivered or opened, has been read for the first time through X-rays and computer algorithms, preserving the complex folds used to turn the letter into its own envelope at a time when paper was scarce and expensive.

The letter was sent on 31 July 1697 by Jacques Sennacques in Paris to his cousin Pierre Le Pers, a French merchant in the Hague, requesting a certified copy of the death notice of of their relative Daniel le Pers. It was never delivered but remained with hundreds of orphaned letters in a leather trunk owned by the Dutch postmaster. The trunk was given to a postal museum in 1926 but only opened and studied in the last decade by the Unlocking History Research Group, an international team including historians, conservators, scientists and computer engineers, from universities including including Leiden, King’s College London and Queen Mary University London, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Yale.

Their success in virtually unfolding and reading one of the letters, described by the team as “conservation led” and published today in Nature Communications journal, has implications for sealed documents in many archives, including thousands of letters in the National Archives in London, where the historic fabric may be as or more valuable than the contents. It was done through applying computational flattening algorithms to penetrating X-ray microtomography scans of the sealed letter, and the technique will now be applied to other letters in the collection.

“Sometimes the past resists scrutiny”, the team writes. "We could simply have cut these letters open, but instead we took the time to study them for their hidden, secret, and inaccessible qualities. We’ve learned that letters can be a lot more revealing when they are left unopened. Using virtual unfolding to read an intimate story that has never seen the light of day—and never even reached its recipient—is truly extraordinary.”

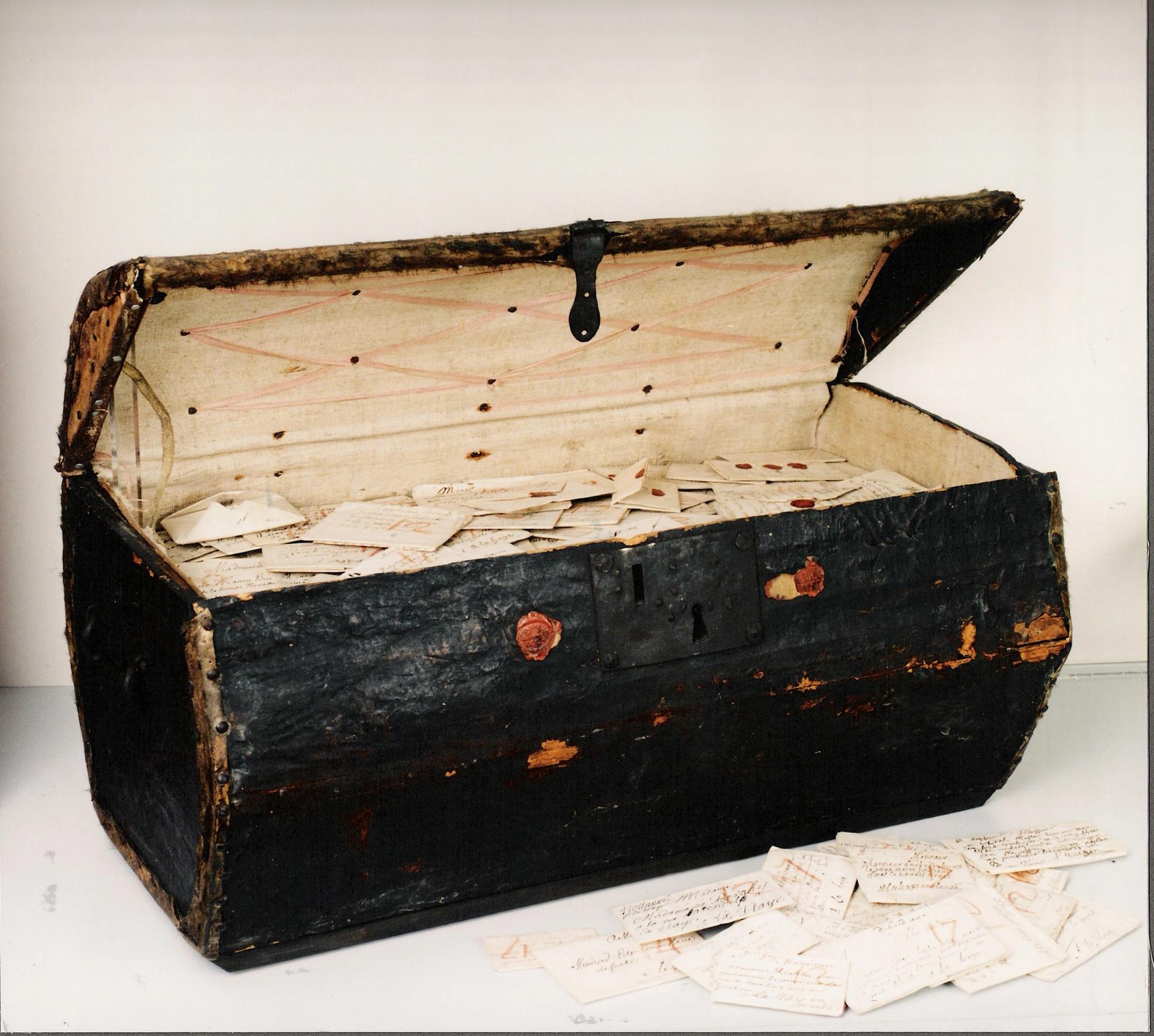

The Brienne trunk © Unlocking History Research Group

The Brienne Trunk, named for the postmaster who originally owned it, contained 2,600 undelivered letters, 600 of them never opened. Some of the intended recipients had changed address and were untraceable, some refused to accept them—including the presumed father of a desperate singer’s illegitimate baby, whose friend wrote appealing for help—but at a time when recipients paid the delivery charge, many may simply have been unable to afford to accept their letters.

The letters from many women, traders, artists, musicians, and travellers, some beautifully written, some barely literate, some including hand made love tokens, in Dutch, French, Spanish and Italian, represent a cross section of the words of ordinary people whose voices are poorly represented in conventional records.

Many of the letters which would have been wrecked by simply unfolding them were sealed by letterlocking, a system of complex folds and cuts used from the 1500s to turn the writing paper into a secure container: some examples have more than 30 folds, but most surviving in archives have been damaged by being opened.

The trunk and some of its contents are on display at the Sound and Vision media museum in the Hague.