Covid-19 has laid bare the unsustainable expectations of an increasingly stratified market and the narrowing margins of both creative and financial success it yields. But the Los Angeles gallery Commonwealth & Council has revised its business plan to rethink how small and mid-level galleries can turn a profit and support their artists in both lean and flush times going forward.

Started by Young Chung over a decade ago as an apartment gallery in LA’s Koreatown, Commonwealth & Council quietly announced via its holiday newsletter last week that it has started the Council Fund, an initiative that would help support artists’ financial needs that are normally outside of the scope of a traditional gallery, like health insurance, personal emergency aid and the development of non-commercial projects.

How? By asking their patrons to consider contributing all or part of their typical discounts toward the fund instead.

“Discount culture in the art world is just a made up thing,” says Kibum Kim, who joined as co-director of the gallery in 2017 and has helped the gallery scale up its commercial endeavours. He adds that these customary discounts extended to collectors by many galleries—which can range from 5% to 50% or more—are a nod to the gift economy of the philanthropic class and a way to build trust with repeat buyers. But these markdowns have no real purpose besides ingratiating dealers to wealthy collectors who rarely need the financial break.

“It’s a practice that ultimately ends up devaluing an artist’s work on the marketplace, not to mention underpaying them for their labour,” Kibum says. He notes that around half of the gallery’s 30-odd roster of artists—which includes rafa esparza, Gala Porras-Kim, Carmen Argote, Clarissa Tossin, Joon Kwak, Jennifer Moon and Jen Smith, to name a few—have other jobs in teaching or service to help support their art careers.

The “discount” percentage of any work bought from the gallery will be paid into the fund and then disbursed quarterly. Who or what the funds are donated to will be decided by a vote among the artists. Chung and Kim are still figuring out how to structure the fund so that it can be easily and quickly distributed without too many tax strangleholds. “We’ll be running these funds separately from the gallery’s operating expenses, of course. We’re exploring 501(c)(3) status so that the contributions would be tax deductible—one of the first questions we received from most of the patrons we approached,” Kim says, noting that the charitable organisation tax code has some limitations.

Earlier this year, the dealers also initiated the Commonwealth Trust created from a pool of works of art all priced at around $20,000, submitted by artists represented by the gallery. The works will be held for a certain amount of time in order to “mature” and accrue value—according to Kim, maybe ten to 20 years. They will then be sold off and the profits split evenly between the dealers and artists who contributed (or their beneficiaries).

“Artists experience success at varying levels and different times. What we want to do is envision a redistribution of resources within the gallery system, instead of this winner-take-all, art 'star' system at play now,” Kim says. “How do we all rise together?”

The trust is a grassroots riff on the Artist Pension Trust (APT), an investment vehicle specialising in blue-chip contemporary art started in 2004 by tech entrepreneur Moti Shniberg, business professor Dan Galai and David A. Ross, former director of the Whitney Museum and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and which merged into the MutualArt Group in 2016 with more than 2,000 artworks valued at more than $100m.

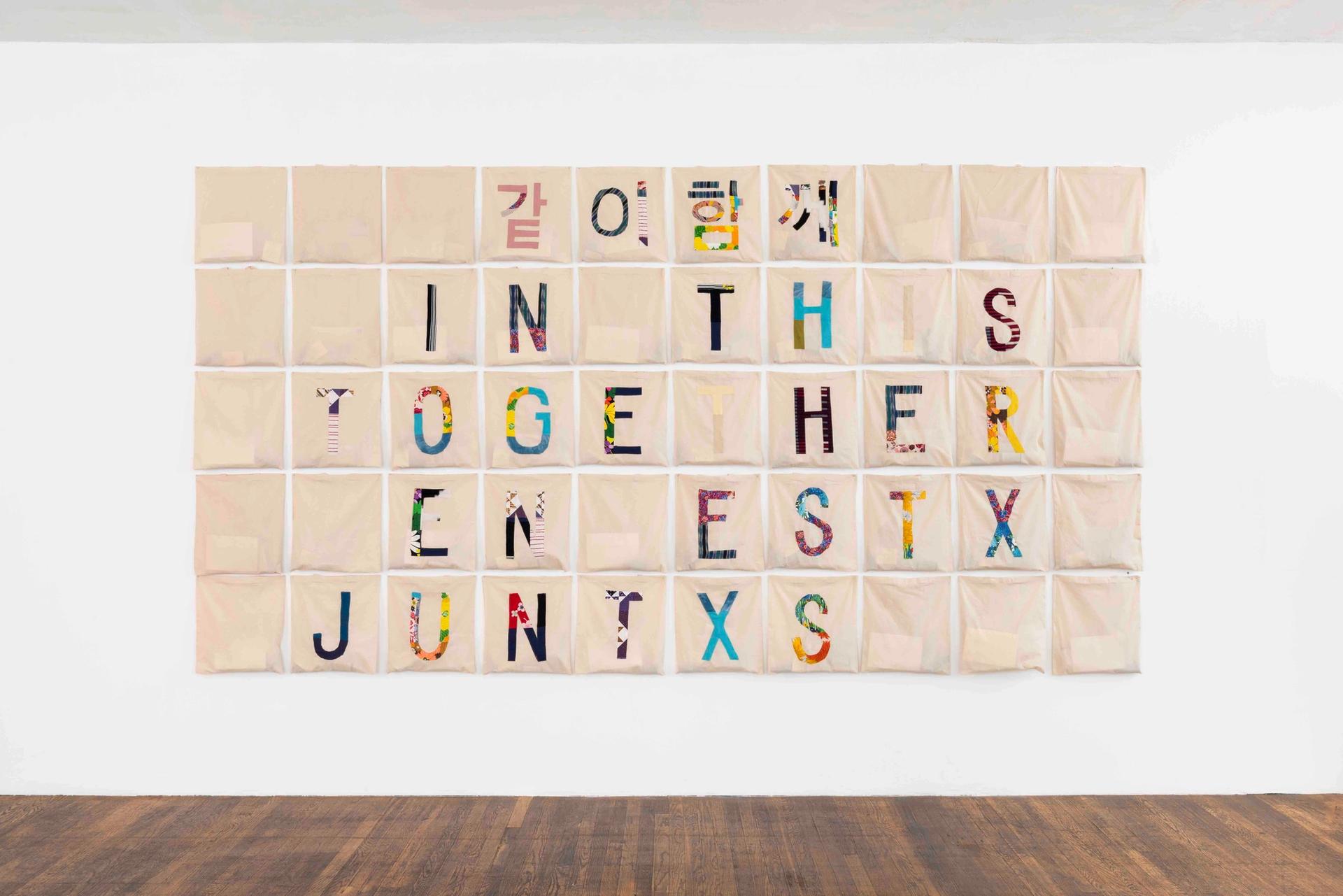

Jen Smith's Take Care (2020) installation view, Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles Photo: Ruben Diaz

The past year has seen several rethinks of existing artist-focused art market interventions. In June, the Paris and San Francisco-based interdisciplinary contemporary arts organisation Kadist contracted the lawyer Laurence Eisenstein to reimagine the Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement—originally created by conceptual art dealer and curator Seth Siegelaub and lawyer Robert Projansky in New York in 1971—by updating the contract’s resale royalty clause to redistribute it as a tax-deductible donation to a charitable organisation designated by the artist.

Continuing in the conceptual vein, US artist David Horvitz has returned to selling his debt as a work of art to collectors, a practice he started nearly a decade ago in light of the credit crisis.

Other more mutual-aid driven initiatives have also arisen to help support creatives through the pandemic, such as the successful #ArtistSupportPledge started by the British artist Matthew Burrows, which asks artists to sell work directly through Instagram with the hashtag. The participants pledged to then spend £200 (or dollars or euros) on other works once they sell £1,000 of their own, to support fellow artists. Burrows estimates that the hashtag’s use has increased more than sixfold since May, yielding an estimated £60m in sales generated by more than 50,000 artists around the world.

The Council Fund, however, differs from these as it puts the onus on the patron rather than the artist to pay into the collective pot. But Kim says that all of these recent initiatives, catalysed by Covid-19, could have far-reaching implications, especially if other galleries implement them. It is no surprise that people are rethinking how the trade works because it has been dysfunctional for a lot of those involved for some time, he explains.

But Kim is also quick to admit that he does not have the perfect solution: “The Council Fund and the Commonwealth Trust might have to shift or change over time. We haven’t figured them out fully yet. But imagine getting through this year and not trying to do anything differently and just waiting for things to return to normal, whatever that means,” he says. “Thinking ahead to the next year, five years, ten years, we want to imagine a market system that we actually want to be a part of.”