UPDATE: France will return 27 colonial-era artefacts in museums to Benin and Senegal within one year, following a unanimous vote by the National Assembly on 17 December.

CORRECTION: This article mistakenly stated that the French Senate had blocked the restitution bill. The Senate approved the restitutions, but added an amendment to the bill that the government refused. The National Assembly has the power to override the Senate, as it did on 17 December by voting through the restitution bill. The article also wrongly conflated the Senate’s decision on the bill on 15 December with its separate presentation of an information report on the issue of restitution on 16 December. The article has been updated to rectify these errors.

The French Senate has clashed with the government over a highly anticipated bill that would return 27 colonial-era artefacts in museum collections to Benin and Senegal, after the two houses of Parliament disagreed on the terms of the new law. The dispute comes more than three years after President Emmanuel Macron’s landmark commitment in 2017 to ensure the “temporary or definitive restitution of African heritage to Africa” before his mandate expires in 2022.

If passed, the bill would compel France to return 26 royal artefacts plundered in 1892 by French troops from the palace of Abomey in present-day Benin, currently held at the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, as well as the sword of a west African military commander, which is already on loan to the Museum of Black Civilisations in Dakar from France’s Army Museum. New laws are needed to remove individual objects from French museum collections because of a 16th-century legal principle that considers national heritage “inalienable”.

Although the National Assembly and the Senate both unanimously approved the bill on its first reading, a joint committee of senators and deputies failed to reach an agreement on the final wording last month. The division centred on the Senate’s call for a national council that would advise the government on restitution claims and regulate similar legal procedures in the future. Deputies rejected the proposal, as well as the Senate’s request that the term “restitution” in the draft law be replaced with the more neutral wording “return”.

On 15 December, the Senate declined to adopt the bill on its second reading. Centrist Catherine Morin Desailly, the head of the Senate culture committee that backed the proposal for an advisory council on restitution, said that “there is no need to further debate this text on which we will not be able to agree”.

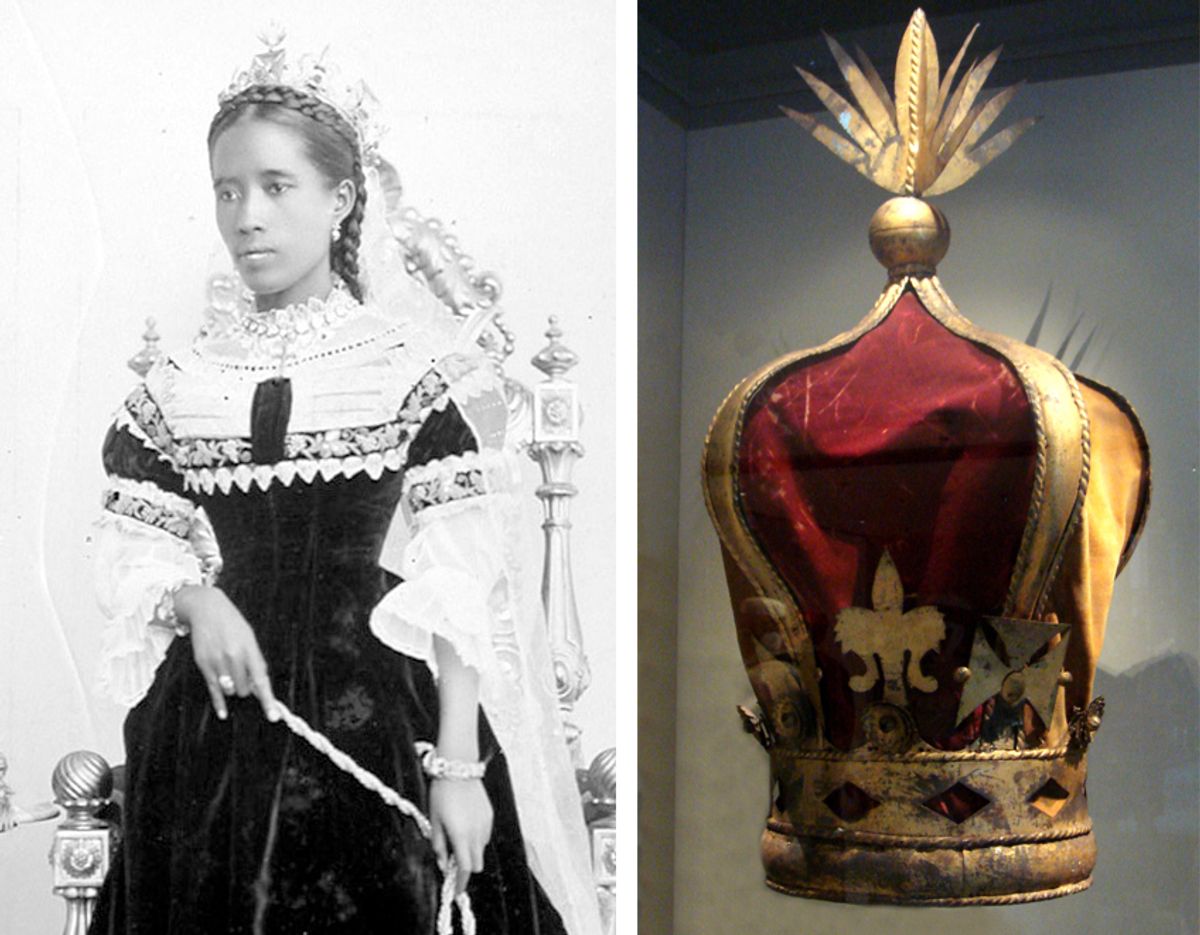

Morin Desailly and other senators denounced the government’s recent decision to return the crown of Madagascar’s last queen, Ranavalona III, as a long-term loan from France’s Army Museum via diplomatic channels, bypassing Parliament. The loan agreement came with France’s promise to initiate legislation allowing the crown’s permanent restitution to its former colony—meaning a new bill will have to be approved by Parliament, and so on for each new restitution. Malagasy authorities had requested the crown’s return in February to mark the 60th anniversary of the country’s independence.

On 16 December, in a press conference presenting further Senate proposals on the issue of restitution, Morin Desailly said: “We must establish a democratic, transparent and scientific method [of restitution] which clarifies political decision-making.” It is a “dangerous process”, she said, if a head of state “removes objects from French collections as diplomatic gifts”.

The Senate’s fact-finding committee outlined 15 recommendations including more touring of France’s public collections, digitising non-Western art and training museum professionals in claimant countries.

The committee also recommended the adoption of a law allowing the restitution of 7,000 items of human remains from more than 60 French public collections. The Senate intends to discuss a new bill about the process of restitutions in January.