More so than any art event culled by Covid-19 this year, it seems that the cancellation of Art Basel in Miami Beach (ABMB) has prompted the most visible outpouring of wistfulness for art fairs among those in the trade. On social media, dealers and art professionals writ large have been sharing misty-eyed memories of ABMBs past, tagging each other in old fair booth installation shots and Joe’s Stone Crab dinner photos while reminiscing on what it feels like to be Ruinart tipsy by lunch.

But despite the nostalgic tributes to the “good ol’ days” in Miami, the city has more physical art viewing experiences than many others have in recent months, even in the absence of its keystone fair. The reason might be the simple fact that many people are starting to get over OVRs (online viewing rooms).

“An online exhibition is not an exhibition. An online viewing room is a shortcut to a sale, but it doesn't do the same work as an exhibition. The internet is only in your mind; art is fiction for your body,” says Ramiken gallery owner Mike Egan. “The only way to build an artist's career from scratch is exhibitions. People have to see the work in person, over and over, to start to understand an artist's ideas.”

An up-and-coming Brooklyn-based gallery, Ramiken is one of many that has launched a longer-term pop-up space in Miami’s Design District, which has generated a season-long presentation of international dealers that regularly exhibit at ABMB, including Lévy Gorvy in collaboration with Salon 94 Design, and Mitchell-Innes & Nash joined by Jeffrey Deitch. Additionally, the Miami-based David Castillo Gallery has opened a second space in the neighbourhood. And Design Miami—owned in part by Art Basel—opened a scaled-down version of its annual fair on 27 November, with just ten galleries displaying installations at the Moore Building, as well as offering all their works in an online shop. The mini-fair runs concurrently with the online-only version of ABMB, which opened Wednesday and runs until 6 December.

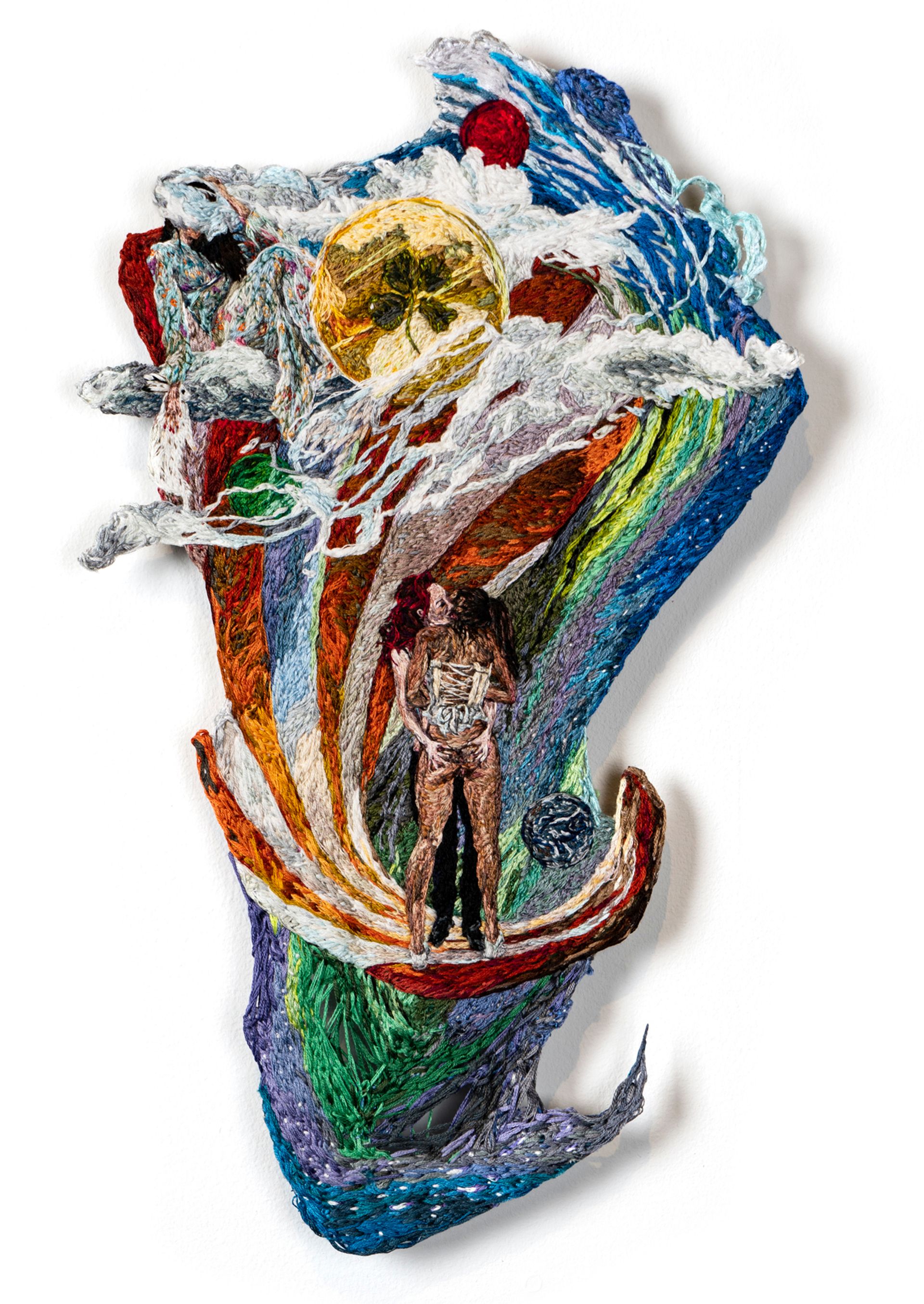

Keeping collectors engaged in an OVR remains the biggest hurdle to virtual events. "Online art fairs present a new challenge for the gallery, since we can no longer interact with collectors in person. However, what we do is work behind the scenes, weeks and months prior to ABMB, contacting collectors and museums and introducing them to the works we plan to have in our booth,” says Michael Kohn, whose eponymous Los Angeles gallery is showing works by Caroline Kent, Kate Barbee and Sophia Narrett, among others, in his OVR. Within the opening day of the fair, the gallery sold a large-scale painting by Kent for $28,000, a Barbee painting for $20,000 and an embroidered work by Narrett for $9,500, as well as other works by William Brickell, Heidi Hahn and Ilana Savdie.

Sophia Narrett's "Someday" at Kohn Gallery. Courtesy of Kohn Gallery

“So far it has been extremely successful, in large part because ABMB is such a highly anticipated art fair, whether it’s at the Convention Center or on screen," Kohn says.

Egan, however, saw the opportunity to be in Miami IRL (in real life) without the draw of ABMB as an opportunity. “In the face of eternity, the pandemic is just another moment in time, like tears in the rain,” Egan says. “I show a lot of sculpture, which creates space that must be experienced in person.” Ramekin’s pop-up presentation features new works by artists Andra Ursuta, Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Eli Ping, Sven Sachsalber, Kristi Cavataro, and Phillip John Velasco Gabriel.

“I have a dozen great supporters in Miami who have been following the artists I work with for years,” Egan adds, noting that the temporary gallery requires reservations and masks in accordance with social distancing best practices. “This was a chance to bring the art to them, in a relaxed fashion. This is an opportunity to do Miami, my way.”

And the art world in Miami has been doing things its own way for pretty much the duration of the pandemic. “The way we do business hasn’t really changed much since clients usually made appointments anyway—Miami isn’t really a walkable city,” says Nina Johnson, who is presenting four smaller exhibitions over the course of Miami Art Week, including new abstract works by Rochelle Feinstein, paintings and drawings by Nathalie Provosty, as well as sculptures by Woody de Othello and Emmett Moore. “For better or worse, the lack of guidelines from the city has allowed us to operate pretty much the whole time.”

Florida’s lax lockdown legislation is a large part of why so many art events are still underway this season, and it has proven a lure for collectors and dealers alike. Yet it comes with an excessively high human cost from which most of the overwhelming white, wealthy, health-care-having art world is insulated. Indeed, the rich have largely played by different rules since the start of the pandemic, fleeing to various coastal vacation homes first in the Hamptons, then in Florida. The recently and seemingly happily divorced art collector Lisa Mugrabi told the New York Times last week that she intended to host a large dinner that would be the "talk of the town" while she was in Miami this year. When asked if she was concerned about the soirée becoming a super-spreader event for her guests, she answered simply: “They can wear a mask if somebody wants. I won’t wear one, but other people can.”

In the face of eternity, the pandemic is just another moment in time, like tears in the rainMike Egan

Florida is the third state in the US to record one million cases since the pandemic began in March, according to the New York Times Covid-19 database (the other two are Texas and California). Miami-Dade county alone has a total of 234,054 confirmed cases and 3,860 deaths as of Wednesday—the same day that the US recorded its single-worst daily death toll since the pandemic began and Covid-19 hospitalisations also hit an all-time high. The Center for Disease Control says the pace of loss shows no signs of slowing any time soon despite the promise of a vaccine.

As the Miami Beach Convention Center remains a busy Covid-19 testing site, what the persistence of Miami Art Week seems to reveal to some is not the resilience of the art market, but how quickly its memory—and its morals—fail.

“The people going to Miami this year for whatever is happening there now, it’s desperate in my opinion. The fair has been such a spectacle for so long—have people already forgotten that they used to complain about having to jump through all its hoops each year?” says KJ Freeman of New York’s Housing gallery, who is participating in the New Art Dealers Association's (Nada) annual Miami event, which takes the ultimate socially distanced form of a fair—asking exhibitors to stay home and put on shows in their own spaces. These exhibitions will then be featured on the fair’s website, which runs until 5 December.

Nathaniel Oliver's "Ashore Beginning", included in Housing's Nada presentation. Courtesy of Housing

Freeman admits the online version of the fair lacks the same flair of the physical version. “I’ve gotten a handful of online inquiries, that’s good. But to be honest I already sold some work before the fair”, she says of her show featuring works by emerging multidisciplinary artist Nathanial Oliver, priced between $3,000 and $8,000. She adds that with the pandemic’s forced move to all-online sales activity, she is less dependent on the crunch-time of fairs.

“The fair feels more secondary now, but Nada has been great for rethinking what fairs can offer in this time", not just in their format but who they include, Freeman says, noting that several new international galleries joined the Miami roster this year, as well as dealers like Kendra Jayne Patrick who do not have physical spaces—previously considered a disqualification for many fairs.

“That’s where change can be made. Nothing about a pop-up and a party in Miami is changing anything about the art world right now. In fact, that’s the culture in this industry that most needs to die. I’m not against a party, I love to party. But a party shouldn’t override the work people put in and it most certainly shouldn’t actively endanger people’s health.”