While many European and US art fairs, biennials and other larger cultural events have been—and continue to be—cancelled or postponed well into 2021 due to concerns related to Covid-19, their African counterparts are going ahead—with caution. They are, however, finding not only support but success, stoking optimism for more emerging markets amid a global economic downturn.

“Cancelling was not an option,” says Nicole Siegenthaler, the manager of FNB Art Joburg in Johannesburg, South Africa (until 18 November) is going ahead in an online-only format, as many fairs have done, but also with two distinct sections. The first part of the fair is a virtual and augmented reality exhibition put on by Gallery Lab, which started as an online sales platform for emerging galleries and artists and launched its first physical space in 2019. The second will be a pared down online presentation that includes more established galleries such as Goodman Gallery and Red Door. Siegenthaler adds that African galleries have always had to be “innovative”.

Perhaps the most influential step that the fair has taken is to relax its exhibitor selection rules to include presentations by independent curators and galleries that do not have a bricks-and-mortar space—previously a disqualifier for applicants to most major fairs. Siegenthaler says that this decision is timely, given that the pandemic forced all dealers to conduct business outside of a physical gallery space. It is also more reflective of how the art ecosystem functions across the African continent, since full-scale physical gallery operations remain in the minority compared with online ventures.

Indeed, responsiveness to a rapidly changing world has required lots of last-minute decisions. Art X Lagos, Nigeria's pre-eminent art event, was postponed from 6-15 November to 2-9 December in solidarity with the ongoing #EndSARS protests against police brutality that have pervaded the West African country for weeks. The protests began at the beginning of October in response to the violence perpetrated by SARS, Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad, which was launched in 1992. The unit stands accused of carrying out unjust arrests, discrimination, extortion and torture of innocent citizens and, since the protests began, thousands of young Nigerians protesters have been subject to violent, deadly crackdowns carried out by government soldiers.

When the fair goes ahead in December, it will now include a new section, New Nigerian Studios, which will present 100 protest works, created by artists after the fair's leadership put out a call for works documenting the historic civil uprising.

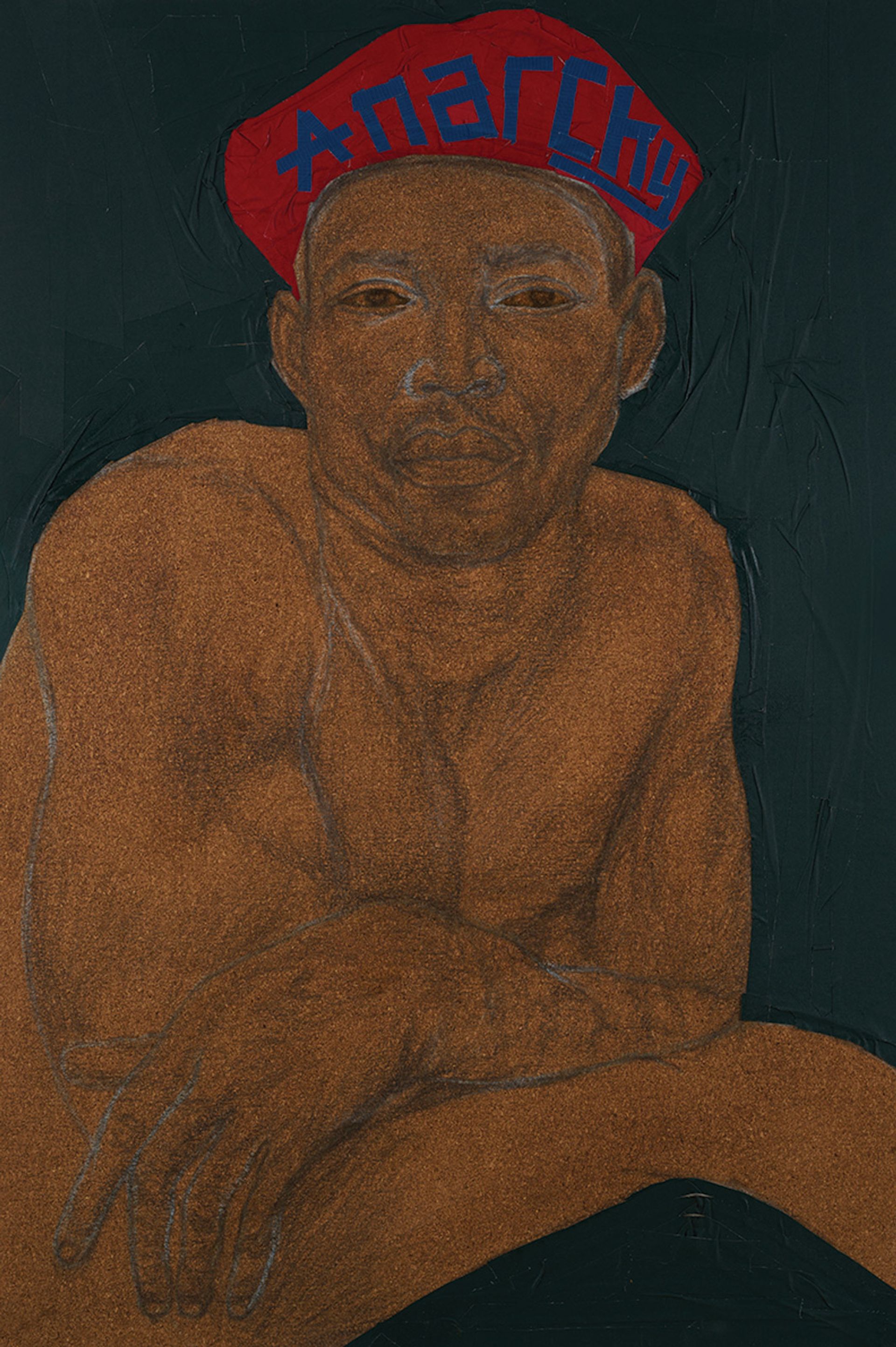

Gallery 1957 presented Serge Attukwei Clottey’s Humble Lion (2020) at the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London Photo: Nii Odzenma

“We were determined to put on the show but what has changed is what kind of show it will be,” says Tokini Peterside, the founder of Art X Lagos. Additionally, the fair—the largest in West Africa— features a scaled-down exhibitor list of just ten galleries, including Nike Art Gallery and Louisimone Guirandou Gallery, presenting more than 200 works that explore histories grounded in Africa and its people.

Overall, a sense of optimism has pervaded the African art market, despite market volatility and the overnight evaporation of global art fair traffic. The continent’s local collector base has found its foothold in recent years, according to many dealers, making them less dependent on Western fairs to reach buyers. That is why, for instance, two new galleries—kó, founded by the established dealer Kavita Chellaram, and ADA, founded by the art adviser Adora Mba—have opened this autumn in Lagos and Accra, Ghana, respectively.

African galleries are also expanding into the European marketplace at a good clip in the absence of fairs. Accra’s Gallery 1957 launched a new space in London last month—before a new round of nationwide lockdowns went into effect at the beginning of the month—due in large part to Ghana’s strict six-month lockdown earlier this year which prohibited works and people travelling in and out of the country. But Victoria Cooke, the gallery’s director, says “this unusual climate became an advantage” for sales since collectors get more one-on-one time with the gallery staff thanks to social distancing.

Moreover, demand for works by artists from Africa and the Black diaspora at large is on the rise. Cooke notes that, on the opening day of the 1-54 London fair last month, which went ahead despite the fact that it has been a satellite event of Frieze since 2013 (Frieze London went online only), the gallery sold out its stand of new works by Yaw Owusu, Gideon Appah, Tiffany Alfonseca and Kelechi Nwaneri. “I think it [was] certainly one of our strongest fairs to date,” she says.

There is certainly more of an appetite for work by Black artists but I try to make sure 70% of our collectors are BlackOyinkansola Dada, Polartics gallery

Polartics, a little-known gallery started in Lagos two years ago and which has also now opened a space in London, also sold out its 1-54 London presentation of works by Ekene Emeka-Maduka. “I had a feeling this was going to happen based on the reception to the work before even getting there,” says Oyinkansola Dada, the gallery’s owner.

“Suddenly collectors who have never looked into buying artists of African descent are now in a way much more aware of including them in their collection,” says 1-54 director Touria El Glaoui.

But the market boom for African dealers and the artists they represent comes with responsibility. “There is certainly more of an appetite for work by Black artists but I try to make sure 70% of our collectors are black—African Americans and Nigerians predominantly,” Dada says. She also makes collectors sign contracts that the works cannot be flipped or sold for the next five years, so that the works are not being collected by people who see it as an “exotic” trend.

El Glaoui agrees, voicing a note of caution about the risks that come with market speculation: “You definitely don’t want to build [a business plan] on a mood like this because it won’t last.”