Time has felt rather meaningless in 2020—days seem indistinguishable, weeks and months a blur. Christie’s saw opportunity in this temporal displacement, moving its marquee post-war and contemporary art evening sales in New York forward by six weeks, from November to October. It also threw a Jurassic-era dinosaur into its new 20th-century art sale because even geologic epochs are mere footnotes now.

Despite the prehistoric offering, the high-tech, livestreamed auction was tame at best. Broadcast from Rockefeller Place to a reported 280,000 viewers, it brought in $292m ($341m with fees)—and that includes the record-setting $27.5m hammer price for Stan, the Tyrannosaurus Rex. For the art, though, the total yield for the 59-lot sale was around $266.9m (roughly $309m with fees) against a pre-sale estimate of $277m-$393m, with a sell-through rate of 88.2% (excluding the four works withdrawn before the sale started). Those withdrawn lots included notable and well-advertised works by Brice Marden, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, which were estimated to bring in a combined $40m.

The results are not as robust as the auction house’s first foray into the pandemic-induced “bricks-and-clicks” hybrid sale format, One, which in July brought in $361.6m ($420.9m with fees) with 94% sold by lot. That sale, however, was nearly 30% larger with 80 lots, and nearly half of the offerings were backed by guarantees. This evening’s similarly cross-genre 20th-century sale—which included works by Modern masters like Paul Cézanne, Claude Monet and Wilhelm de Kooning to contemporary heavy hitters such as Mark Bradford and Vija Celmins—saw 16 lots (27%) guaranteed to sell.

Cy Twombly's "Untitled (Bolsena)" sold for its low estimate of $35m. Courtesy of Christie's

Among the top lots of the night were Cy Twombly’s Untitled (Bolsena) from 1969, formerly held in the Saatchi collection and considered one of the best works by the artist left in private hands, which sold for $35m ($38m with fees). With a pre-sale estimate of $35m to $50m and only a handful of bids, its hammer price suggests the most expensive work of the evening may have gone to its guarantor.

Interest in other high-profile lots was similarly low key. Pablo Picasso’s Femme dans un fauteuil, a 1941 painting featuring the artist’s muse, Dora Maar, fared adequately, bringing in $25.5m ($29.5m with fees) on a $20m to $30m pre-sale estimate. But Jackson Pollock’s untitled 1946 red drip painting, controversially deaccessioned from the Everson Museum of Art, hammered at its low estimate of $12m ($13m with fees).

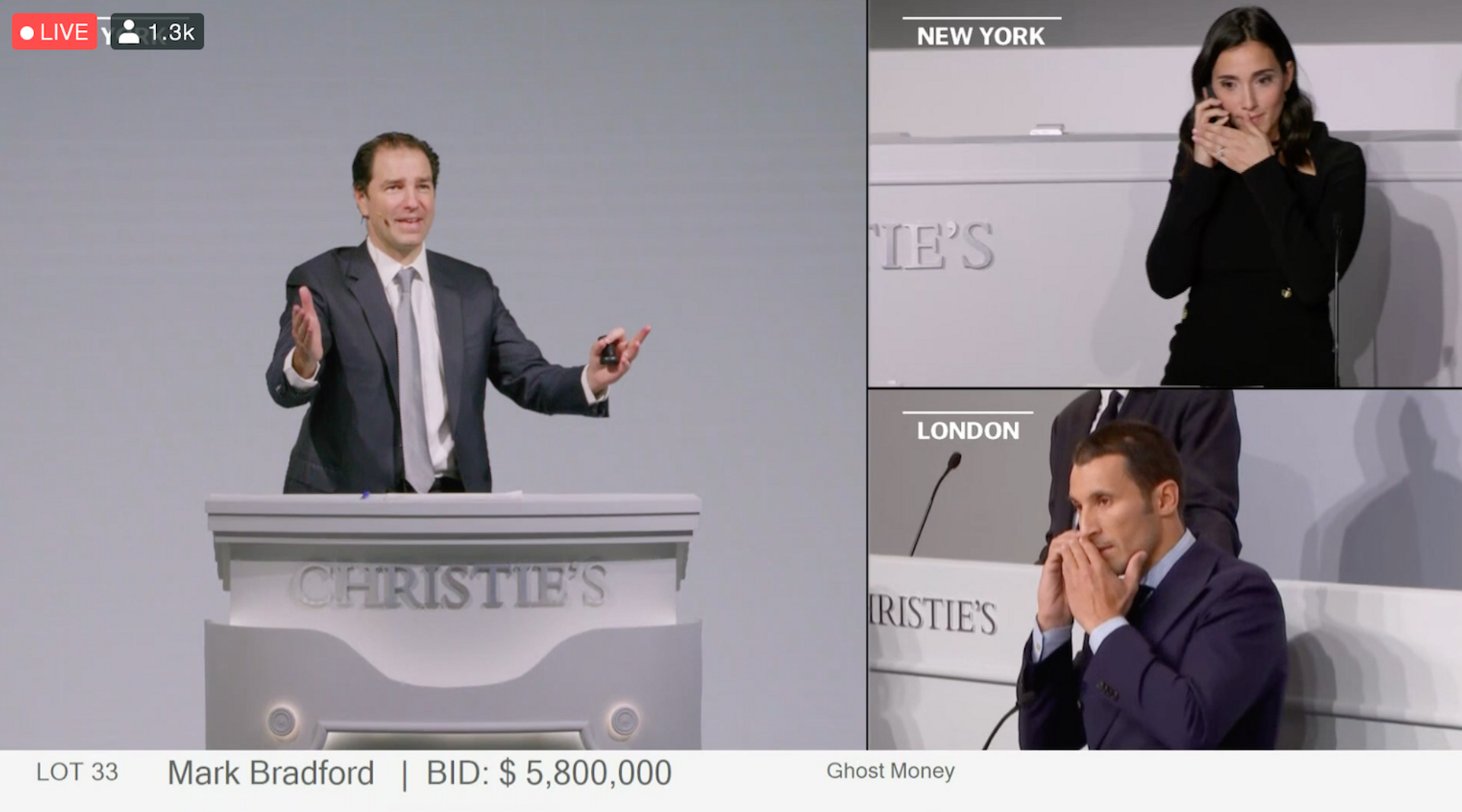

Bidding was strong on Cecily Brown’s I Will Not Paint Any More Boring Leaves (2) (2004), which was last shown at the artist’s traveling survey in 2007 and went for $5.1m to a New York bidder, putting it in the top three most expensive works by the artist ever sold at auction—prices that have all been set within the last three years. Mark Bradford’s mixed-media canvas Ghost Money (2007)—a large-scale work last sold at Christie’s in May 2015 for $3.6m—sold for $7m.

A brief bidding war broke out over Marc Braford's "Ghost Money". Screenshot via YouTube

Works by tried-and-true blue-chip artists like Picasso, Joan Miro, Vincent van Gogh, Fernand Leger, Andy Warhol and Jean Dubuffet all failed to sell, however, and Jeff Koons’s Dolphin was tossed back to sea when it was bought in at $1.5m.

Concern about the impending and already contentious US presidential election on 3 November may have contributed to reticence to splash out among some buyers. Christie’s chairman Alex Rotter noted in a post-sale press briefing that the earlier dates of the sale were not planned solely to avoid any election-related market fallout, “but it’s certainly something we need to think about”.

Morgan Long, the senior director of the Fine Art Group, maintains that her clients have remained largely unfazed by the political upheavals of the last year. “Collectors have already adjusted to considerable uncertainty [in 2020] in every aspect of their lives, and the industry as a whole has adapted at a remarkable pace to the radically transformed trading conditions,” she says, adding that “any sensitivities to political uncertainty are already ‘baked in’ to the current market” and it is not just limited to the US.

“We must not forget the potential impact of Brexit for the European market and current events in Hong Kong and China which also add to the mix,” Long says.

Nevertheless, it is worth noting that tepid results were also had for two high-value works reportedly from the collection of Revlon billionaire Ron Perelman, who has been rapidly offloading art and assets to apparently pay down debts. Willem de Kooning’s Woman (Green), a work from 1953-1955, hammered for $20m ($23.6m with fees), its low estimate. A rare 1967 Mark Rothko painting—the cover lot of the sale—sold for $28m ($31.7m with fees) despite being estimated to fetch between $30m and $50m. Both were sold with guarantees.

Meanwhile, earlier in the day at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, a large Gerhard Richter abstract painting from Perelman’s holdings, Abstraktes Bild (649-2) (1987), sold for HK$214m ($27.7m) to a private institution in Japan, making it the most expensive contemporary Western artwork sold in Asia, according to the auction house.

Whether the confluence of other major sales happening this week, such as Sotheby’s Hong Kong series and Frieze week in London, tempered zeal for Christie’s sale remains unclear. “The consolidation of the art world calendar has been happening for a long time, but it was previously geographically motivated based on when collectors would be in certain cities,” says Drew Watson, the senior vice president of Art Services at Bank of America. “The experience economy is not as relevant to virtual offerings, so perhaps the pendulum may be swinging in the opposite direction."

Of course, Christie’s did make every effort to make this sale an experience. With just one auctioneer, Adrien Meyer, based in New York, roughly half of the works on offer were sold to bidders on the phones with US-based specialists, despite the fact staff in the London and Hong Kong sale rooms were livestreamed in to bid on behalf of Asian and European clients. It was a seemingly needless but technically impressive holdover from the One relay sale format, perhaps, which saw four auctioneers working in tandem across sale rooms in Paris, London, New York and Hong Kong.

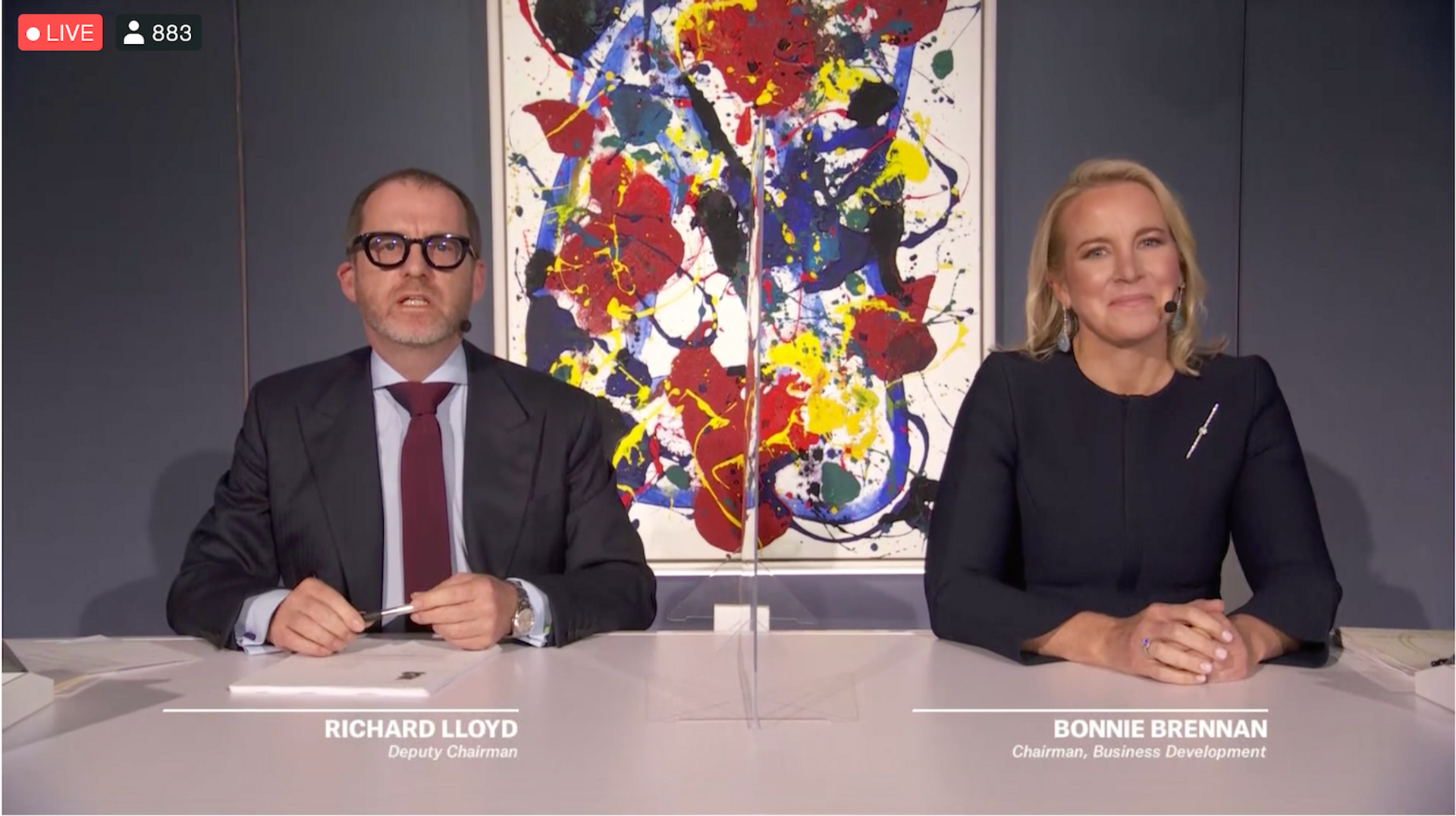

Two hosts provided commentary throughout the sale. Screenshot via YouTube

But do not mistake the single-city rostrum for simplicity. To bring an added sense of occasion to the evening, the event began with a pre-sale augmented reality (AR) show featuring Marc Porter, Christie’s chairman of the Americas, Los Angeles dealer Jeffrey Deitch and Financial Times columnist (and The Art Newspaper editor-at-large) Melanie Gerlis digitally beamed into a virtual gallery with the Manhattan skyline digitally etched behind them. It was a bit like a talking heads pre-game show before a big sporting event but with neither the banter nor news ticker of other teams’ scores to keep viewers engaged.

The sale was further game-ified with two hosts, Richard Lloyd and Bonnie Brennan, who were seated side-by-side (but separated by Plexiglass for safety) and offered commentary during bids throughout the evening. Particularly important lots were introduced with a cutaway video shot of the work and a digital text-and-graphic overlay that diagrammed its medium and dimensions, all set to an ambient yet urgent music track. When bidding became tense, a maudlin strings motif set to the subtle thrum of a heartbeat crept in as Meyer pressed for a price. And, taking a page out of Sotheby’s book, specialists were treated to full makeup to get them camera-ready, and many were draped with gems that will be featured in the auction house’s upcoming jewellery sale.

The real star of the show was still Stan, though. Offered as the last lot in the two and a half hour sale, the nearly complete 67 million-year-old Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton from South Dakota inspired nearly ten minutes of deep bidding, mostly from European clients. It sold for $27.5m ($32m with fees)—more than four times its estimate—to a buyer on the phone with James Hyslop, the UK-based head of natural history at Christie’s, who has been working to bring Stan to the auction block for two years. The result smashes the $8.4m that Sotheby’s fetched for a T-Rex named Sue in 1997, which now resides in the Field Museum in Chicago.