Questions over the authenticity of Russian avant-garde art have plagued the market for decades. Now, a groundbreaking new exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne has begun to provide answers.

The proliferation of fakes has affected the field “like no other”, says Rita Kersting, the museum’s deputy director and a co-curator of the show Russian Avant-Garde at the Museum Ludwig: Original and Fake. Questions, Research, Explanations, which opened last week. Soviet censorship of avant-garde art meant that many works disappeared and could resurface decades later on the burgeoning Western market with incomplete provenance—a gap exploited by forgers.

The exhibition, which runs until 3 January 2021, delves into the process of authenticating 49 paintings in the museum’s collection, amassed by its founders Peter and Irene Ludwig. Home to more than 600 pieces ostensibly produced by members of the Russian avant-garde, including several attributed to El Lissitzky, Natalia Goncharova and Liubov Popova, among others, the Museum Ludwig is scrutinising just a fraction of its holdings in the exhibition.

“We have wonderful paintings in the collection and our visitors expect that what is hanging on the walls here is authentic,” Kersting says. “We have long had suspicions about certain paintings. And this public display is a way of reconciling that.”

Led by conservator Petra Mandt, the museum investigated the works using chemical and materials analysis, ultraviolet and X-ray tests, along with infrared examinations. When research began, “there was an inkling of doubt” surrounding “some of the works”, Mandt says.

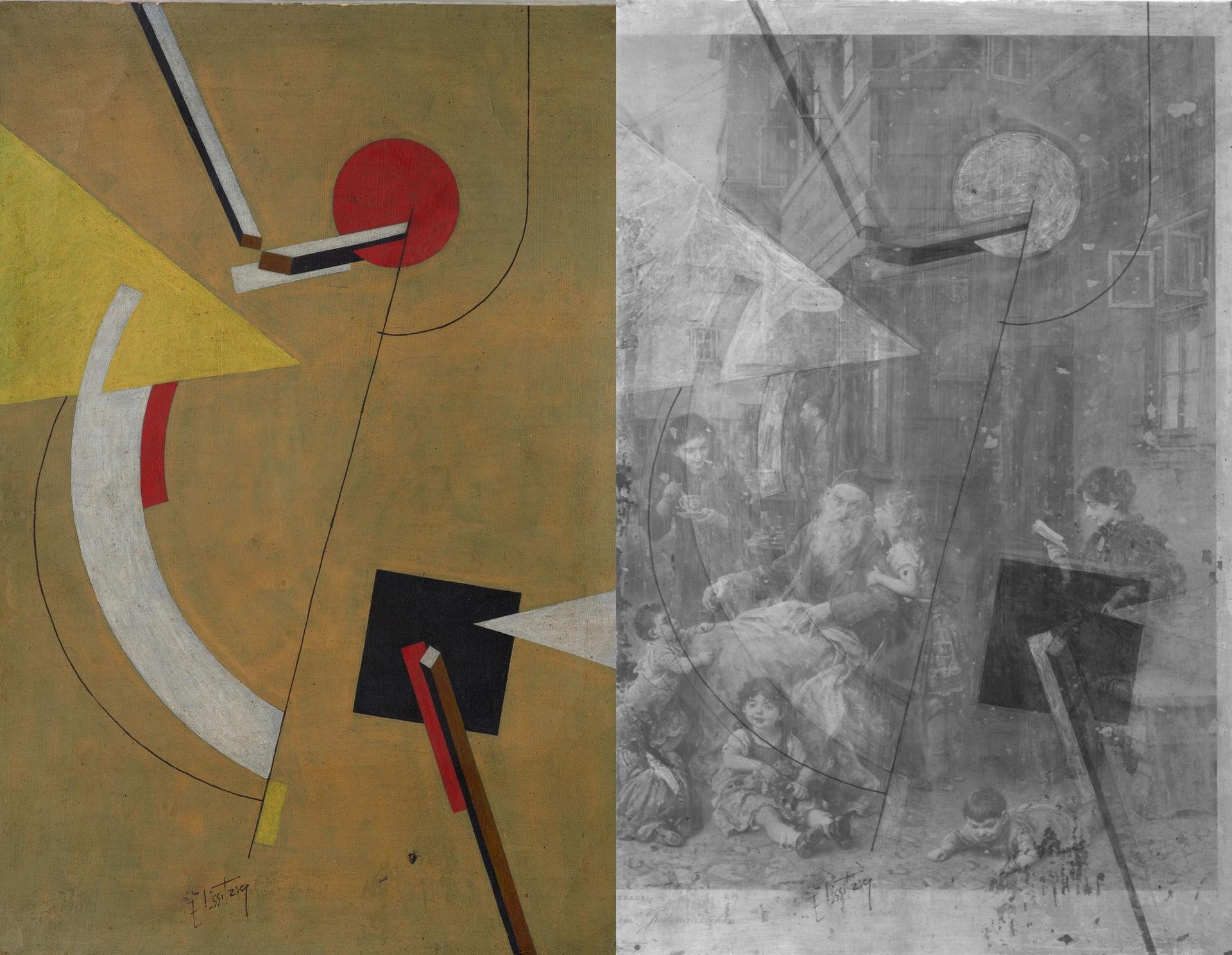

The study has now confirmed that 22 works in the collection were falsely attributed. Among them is Proun, a painting attributed to El Lissitzky and originally dated to 1923. Infrared analysis revealed an earlier painting beneath the surface image, which cast doubt on the authenticity of the work. A comparison with laboratory analysis conducted by the Busch-Reisinger Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, of a similar Lissitzky, Proun 12E (1923), helped to determine that the Museum Ludwig’s painting was a fake.

Infrared analysis cast doubt on the authenticity of Proun, a painting previously attributed to El Lissitzky and dated to 1923 Left: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln. Right: Museum Ludwig Köln / Restaurierungszentrum Düsseldorf / Ulrik Runeberg / Inken Holubec

Proun is displayed at the museum with the results of this assessment and details of the painting’s provenance, materials and technique. Other falsely attributed works hang side-by-side with verified authentic paintings, including loans from the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and the Momus in Thessaloniki. The exhibits invite visitors to weigh up for themselves the similarities and differences between the originals and fakes.

“We see that our visitors look at the works from a different perspective. They view specific aspects with a sharper eye when comparable paintings are seen together,” Mandt says.

“If you stick an authentic Gonchorova beside a dubious one, it doesn’t take a particularly well-trained eye to work out the difference between the two,” the art dealer James Butterwick tells The Art Newspaper. Butterwick, who has called attention to the issue of Russian avant-garde fakes, describes the Museum Ludwig’s exhibition as a “very important reference point” exposing “the massive problems connected with the Russian avant-garde”.

The museum faced a legal challenge over the show from Galerie Gmurzynska, which originally sold around 400 paintings to the museum’s benefactors. The gallery demanded to see the exhibition research in advance, arguing that it could cause damage to its reputation. But a regional court rejected the claim on 16 September, overturning an earlier court decision in the gallery’s favour, which was appealed by the city of Cologne.

Natalia Goncharova's Orange Seller (1916), an authentic painting, was studied by the Russian Avant-Garde Research Project © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2020. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln / Russian Avantgarde Research Project

Suspicious works of art are normally consigned to a museum’s storerooms. And it is likely that the Museum Ludwig will send its falsely attributed works to the depot once the show ends in January. But in going public with its authentication research, the museum has made a clear commitment to preserving accuracy in a field flooded with fakes.

The study of authentic works by two artists in the exhibition, Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov, offer an insight into the techniques available to detect fakes. The Museum Ludwig submitted 14 of its paintings by the artists for analysis by the Russian Avant-Garde Research Project, based in the UK.

A team led by Jilleen Nadolny from Art Analysis & Research Institute, a private London firm, studied the works with technologies including 3D surface scanning. “By looking with the microscope, combined with X-ray and infrared imaging, which allows us to see below the surface, we could confirm how the artists worked,” Nadolny says. “These might look like wild, spontaneous brushstrokes. You don’t see any underdrawings, yet they are there, guiding the artist’s hand.”

“Having a baseline technical analysis like this can help detect forgeries later,” she adds. “It’s a great benefit to understanding an artist’s work, and to protecting their legacy.”

Kersting acknowledges that “it’s painful to have to write a work off”. However, she says: “We think that the artist’s oeuvre should remain in the foreground, not be obscured.” After all, “the artists can no longer defend themselves”.