The opening of a $90m overhaul of San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum has been twice postponed because of the coronavirus pandemic, but this week, the museum unveils a trio of commissions to celebrate the project. The three artists have ties to the Bay Area, but were born outside of Asia: Chanel Miller, a survivor of sexual assault and the author of Know My Name: A Memoir (2019); Jenifer K. Wofford, a member of the Filipina American artist group Mail Order Brides/M.O.B.; and Jas Charanjiva, a street artist and the co-founder of the Indian graphic design showcase Kulture Shop. “I don’t see the ‘Asian’ in Asian Art Museum as a fixed geographical boundary,” says Abby Chen, who joined the institution as its first head of the contemporary art department in January 2019. “It is something more dynamic and ever-changing.”

Most recently the risk-taking artistic director for San Francisco’s Chinese Cultural Center, Chen seeks to “create access points that are really relevant to people today” through works like Wofford’s joyful street-level commission Pattern Recognition (2020), which references the museum’s collection and celebrates Bay Area Asian-American artists like the late sculptor Ruth Asawa in a colourful 1980s-style aesthetic.

Jas Charanjiva works on her mural Don't Mess With Me

Charanjiva’s 318 sq ft rooftop mural Don’t Mess With Me (2020) re-stages the bright pink work the street artist has pasted around her city of Mumbai: a defiant, comic hero-like woman in traditional Indian bridal dress—with brass knuckles reading “Boom”—made in response to the fatal 2012 gang-rape of a Delhi student. Both commissions are due to be unveiled this month, fortuitously visible to passersby, as the opening of the revamped spaces has been twice pushed back due to Covid-19 and is now expected in early autumn.

Jenifer K. Wofford's Pattern Recognition (2020) celebrates Bay Area Asian-American artists like the late sculptor Ruth Asawa in a colourful 1980s-style aesthetic

Miller’s commission, a triptych drawing blown up and printed on vinyl, occupies around 1,000 sq ft of wall space in the new second-floor Wilbur Gallery, where it can currently be seen from the street. The artist, who last year released her first animated video I Am With You, says she has sometimes thought, when given a prominent platform for interviews, “Who am I to fill that seat?”, which she realised “came from a lifetime of not seeing people who look like me in that seat”. This opportunity is “something I needed to do for myself, to see myself there, and to have other people who look like me see themselves there”, she says.

“All of my drawing has enabled me to have the hard conversations, to sit with grief… any time it becomes too much, I can spread paper across my floor, and I can draw myself back to sanity,” says the artist Chanel Miller Photo: Mariah Tiffany, courtesy the artist

When Chen initially reached out to Miller—who last year revealed she was the victim of a highly publicised 2015 sexual assault at Stanford University—she shared the anti-sexual harassment guidelines she wrote for small institutions after an incident at an arts research centre in Guangzhou, China. Miller appreciated that Chen held the institution accountable and saw both the incident and the victim’s healing as a community matter. “I feel like what [Chen] was asking for me is, ‘What’s next?’” Miller says. “And I think that’s the question we [sexual assault victims] fear that we’ll never be asked.”

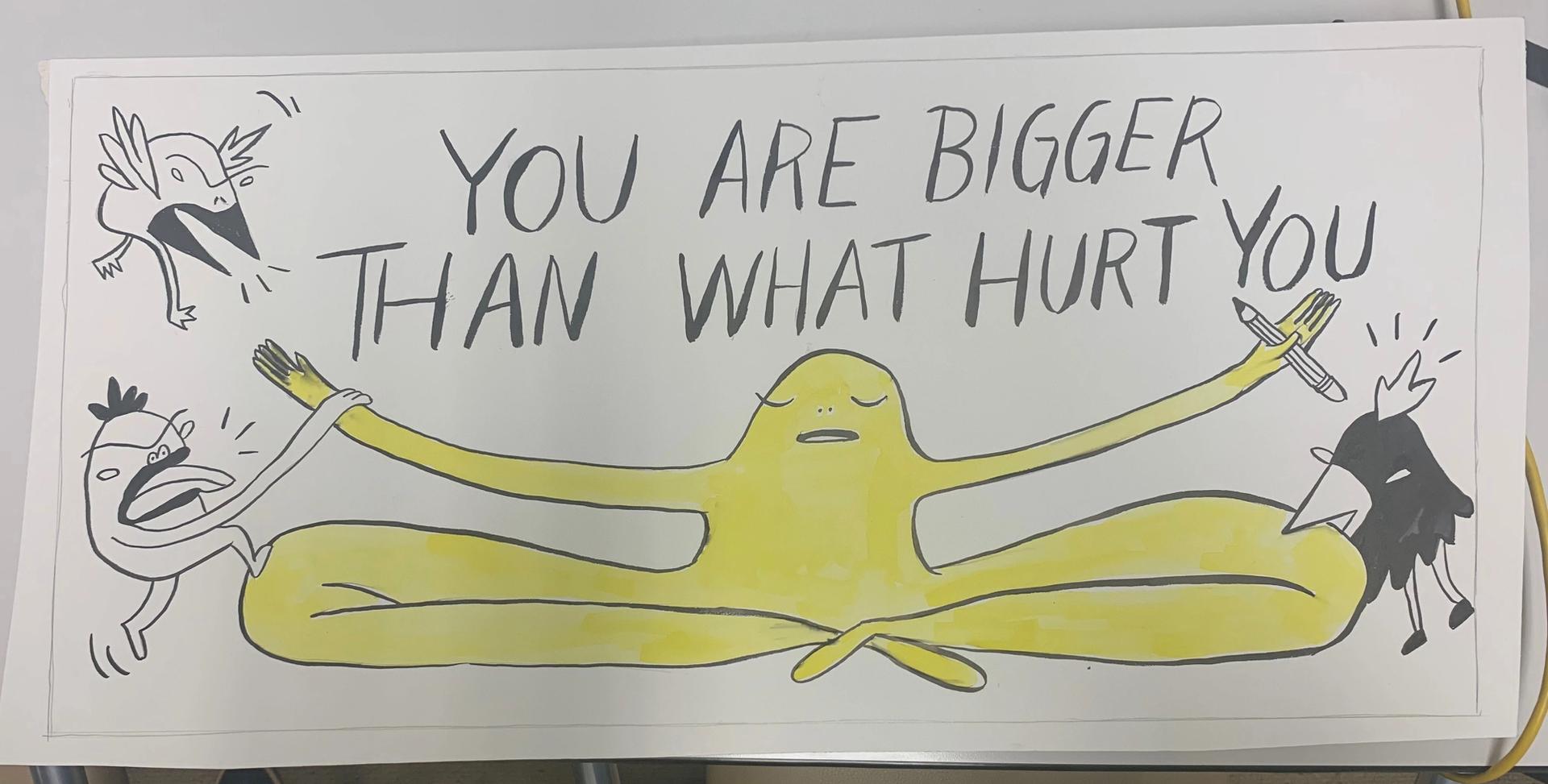

The work “honours transition” and explores the ongoing process of healing, with each of the three chronological, narrative drawings successively labelled I Was, I Am, I Will Be. The mural depicts a charming character in a simple linear style, who starts out curled up in a ball, crying a puddle of green tears, moving through a cross-legged meditative pose, ultimately getting up and walking off, arms held wide and head up, as if embracing a sunshiny future.

Although it is less detailed than many of Miller’s other drawings, which often contain a parade of whimsical creatures (in part, for impact from the street), I Was, I Am, I Will Be retains a feeling of play. “I think the playfulness is the only thing that enables me to go to the darkest parts of me,” Miller says.

“Very simply and clearly expressing that we are always in transition, I hope, is enough to make you realise that wherever you are in your journey… you will never be stuck,” says Miller Courtesy of the artist

“All of my drawing has enabled me to have the hard conversations, to sit with grief… any time it becomes too much, I can spread paper across my floor, and I can draw myself back to sanity,” she says. “Just being able to create a line, I can follow it like a trail to a place where I’m breathing again, where I see that silliness is always present and that I haven’t become entirely cynical or entirely heavy.”

Miller hopes the work, which is especially striking through the gallery’s glass exterior when illuminated at night, will be a reassuring presence. “I think the worst times for me was when I believed that damage was permanent, or that my life would be frozen in one moment,” she says. “Very simply and clearly expressing that we are always in transition, I hope, is enough to make you realise that wherever you are in your journey… you will never be stuck.”

“The process of becoming resonates with how the museum is transforming,” Chen says. “It’s a constant effort and you will have different stages, but I remain very hopeful—and I think that’s the story that Chanel is telling too.”