In Oslo, the campaign to save the Picasso-Nesjar murals on the Y Block Government building has reached a critical moment. Pablo Picasso’s murals, sandblasted into a concrete skin in collaboration with the Norwegian artist Carl Nesjar, are integral to the Erling Viksjø-designed brutalist structure, which is due for demolition at the end of July. As scaffolding goes up around the murals, and the legal battle escalates, Gro Nesjar talks about her father’s 17-year collaboration with Picasso and why the murals’ preservation is such an urgent issue. She has also given The Art Newspaper permission to present previously unpublished photos connected with this largely forgotten period of art history.

The Art Newspaper: What is the latest situation with the murals?

Gro Nesjar: Well, as you know, the grandchildren of the Y Block architect [Erling Viksjø] and I are threatening to sue the Norwegian government if they attempt to take down the murals. [In June] I was made aware of an email from Jean-Louis Andral, the head of the Picasso Museum in Antibes, saying that he had written to [Nikolai] Astrup, the relevant Norwegian minister, expressing his disappointment that the demolition was still going ahead, and asking him to review it one more time.

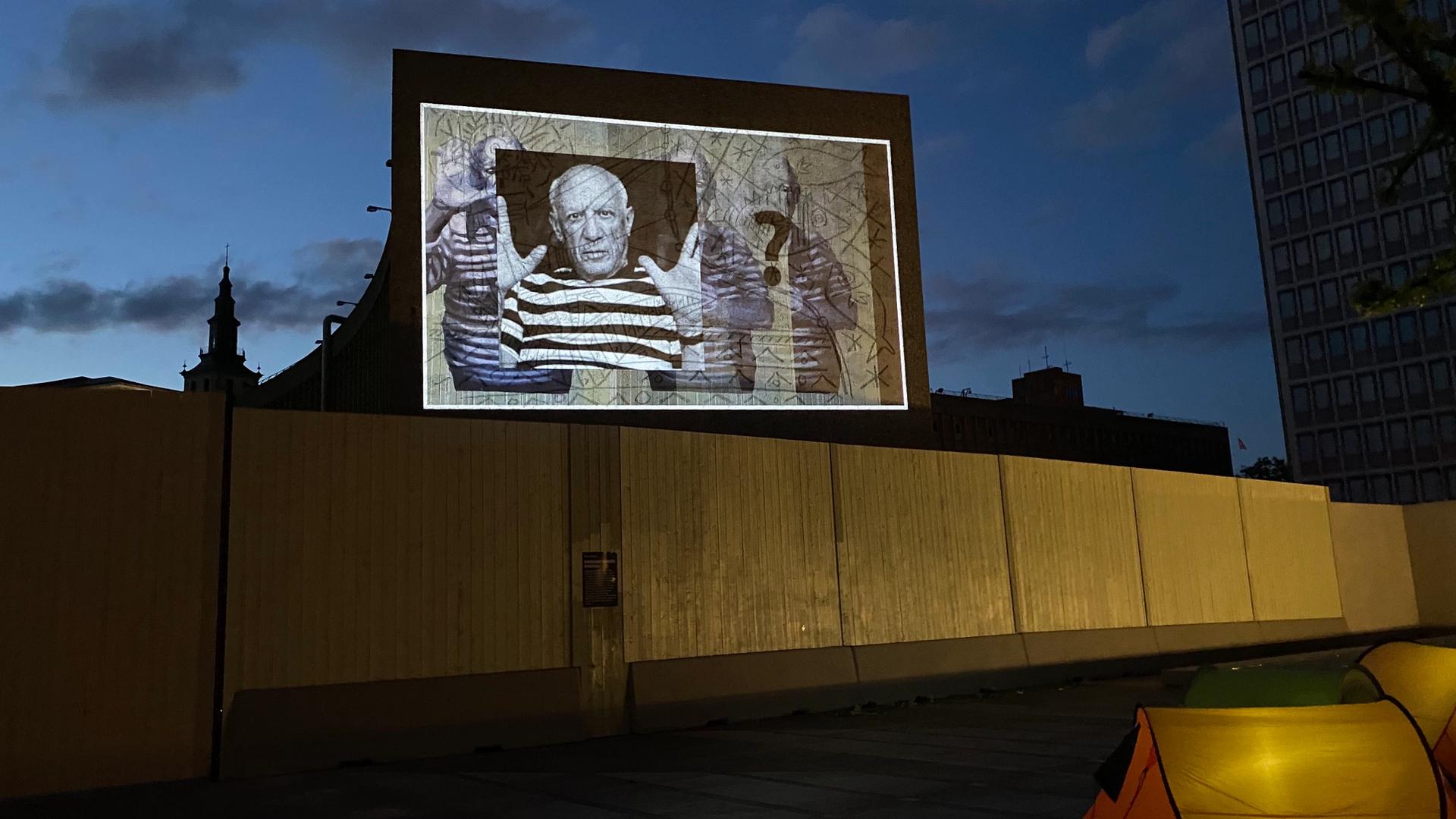

Protest projections on the Y-block by Projektorpøblene © Projektorpøblene

And what is the public reaction?

It’s really taken off during this lockdown period. With all the art museums and galleries closed, the public are rediscovering these art works. I think people are moved by our campaign to save the murals because it represents a less materialistic, more cooperative Norway, a Norway before all the oil money and different values came in. The Picasso murals were a monument to the resilience of the Norwegian people, to freedom, to building a new nation after such a trauma. These themes resonate powerfully with the public at this moment.

A lot of artists have been activating the site, which is now fenced off because of the proposed demolition. They put posters, projections, drawings and flowers up on the fences. And then the authorities tear them down. So it’s become like a fight of putting up posters, then having them taken away again. The whole conflict is linked to the global Covid-19 moment where people are publicly expressing the future they want and how it is connected to the past. The campaign has become about something bigger than the site, bigger even than the story of my father’s collaboration with Picasso.

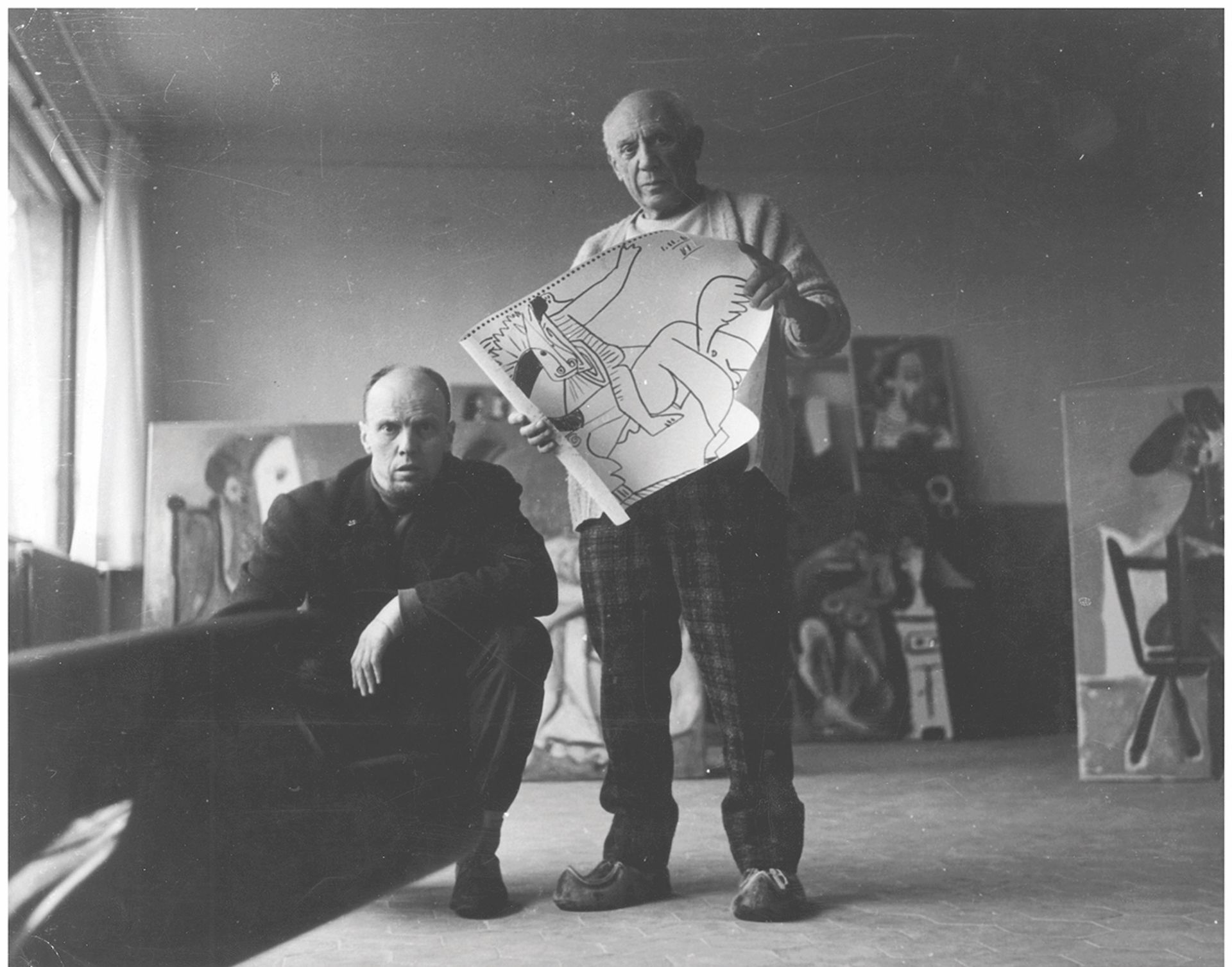

Carl Nesjar and Picasso with the war-horse drawing that was sandblasted into the wall of collector Douglas Cooper’s home, Château de Castille Courtesy Carl Nesjar/Carl Nesjar Archive

So what is this new legal angle that you are exploring?

Well, we now have an attorney and have found the right legal grounds to contest the government’s decision. It turns out that because under Norwegian law the Y Block mural is considered a co-authored art work by Picasso and my father and the architect, we do have what are called “moral rights”, as long as we can prove that the murals are a collaboration—that my father was not just a fabricator for Picasso but part of the artistic process. And Erling Viksjø also has the rights, because the industrial and artistic techniques that made these murals possible, and which made my dad and then Picasso interested in doing this project in the first place, is something he developed with his engineer, Sverre Jystad.

What makes it a collaboration is the fact that my father actually adapted the drawings of The Fishermen and several of the murals as part of the process to fit them to the wall. My father was perhaps the only person Picasso ever let modify his drawings. And Picasso allowed that because he saw the production of these concrete works with my father as an artistic collaboration.

How did they start collaborating?

When they first met in 1957, my father explained the new concrete technique being used for the Oslo government buildings, and Picasso got so excited when he saw the plans that he started to run around the house, showing them to his cook, to his chauffeur, to everybody, because he had finally found a material that would allow him to scale his drawings up as monumental and permanent public art work. So that was the start of that.

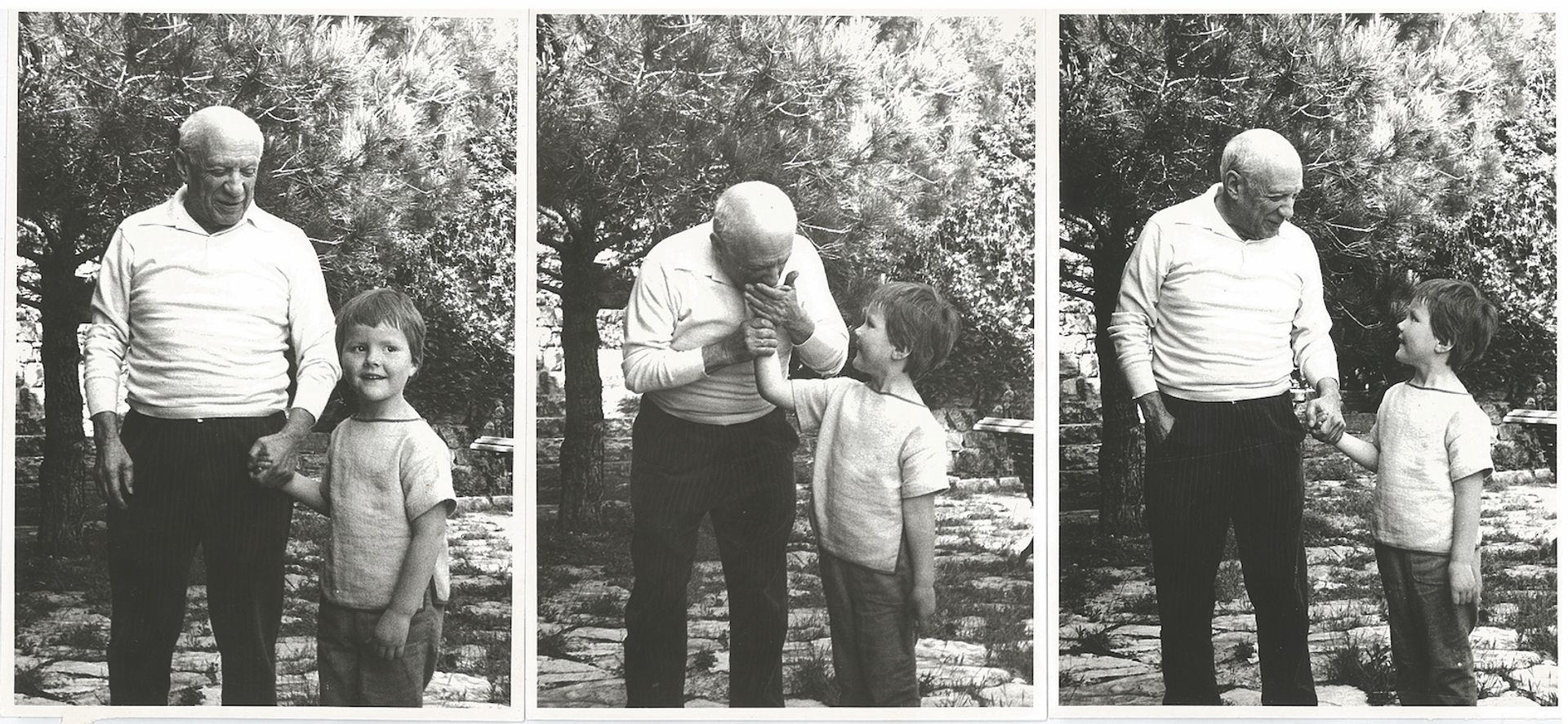

Pablo Picasso with Carl Nesjar’s daughter Gro in his garden in 1962 at the villa La Californie, his home and studio in Cannes Photo: Courtesy of Gro Nesjar

What exactly is the Naturbetong technique?

I think the only difference between Naturbetong and regular concrete is that you mix it with pebbles. It is finished with a smooth, even surface of concrete which can be blasted away to reveal the dark stones beneath. So you actually draw in the concrete by sandblasting a line through the “skin”.

So what was their collaborative process from, let’s say, the idea to execution?

Well, that seemed to vary. For the murals, my father would sometimes suggest an existing Picasso drawing, like the faun drawing in the Picasso Museum in Antibes, which he felt would adapt well to the concrete. Other times Picasso would make a new drawing, like for the Y Block, which he chose as a symbol of Norway as a country of fishermen. My father would adapt the drawings to the dimensions of the wall, and then they would work with the Naturbetong technique. At one of the other two mural sites, the Château de Castille in southern France, Picasso made an incredible drawing of a kind of war horse as a direct response to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. From the outset, my father made a deal with Picasso saying, “I will make it. And if you don’t like it, we’ll just erase them and start again.” So they moved forward with this experimental approach based on trust.

What was their business relationship?

I don’t think there was ever any kind of exchange of money between Picasso and my father. And there were never any contracts between Picasso and the people or organisations that commissioned these public works, including Barcelona and Oslo. It is important to note that for the public art, Picasso was never paid. He never wanted to have any money for those works, because he saw it as a public service, a contribution to society. So the only ones that got paid were the workers. This is one of the arguments that I’ve put forward around the Save the Y Block Campaign: that the murals were actually a gift from one of the world’s greatest artists to the Norwegian state… and what a way to treat a gift!

Carl Nesjar (lying down) with the construction team working on Picasso’s war horse mural Courtesy Carl Nesjar/Carl Nesjar archive

Picasso didn’t trust many people. What was it in your father that inspired his trust?

I think that Picasso would never have trusted my father if he hadn’t respected him as an artist in his own right. Picasso knew the subject matter, but he didn’t know the material, so he didn’t know which lines would actually translate best to the concrete. My father understood the translation of the drawings onto the material.

Despite the age gap—I think my father was 35 and Picasso was 70 when they met—they shared political as well as artistic views. Picasso was a communist, and although I don’t think my father was a communist, he was probably very close! I think they also developed a really close friendship. The tone of their letters from 1960 through to ’63 shows this in a way I hadn’t fully grasped before.

Picasso didn’t like writing letters, so Jacqueline [his second wife] wrote most of the letters to my father. He preferred to meet my father in person and invited us to stay with him in France a lot. Our family kind of became part of his family. My dad would travel with Picasso to see other artists, go out for a meal, spend days on the beach. They laughed a lot. I think Picasso felt very safe with my father and our family.

Stephen Stapleton and Gro Nesjar in front of the Picasso-Nesjar horse mural at the Chateau de Castille in Southern France Courtesy of Stephen Stapleton

What memories do you have of being with your father and Picasso at that time?

Well, I remember in 1962 he made two masks that I could play with in his studio at La Californie [in Cannes]. I thought he had a most wonderful car. I had never seen a car like that. I had never seen anybody who had a cook or chauffeur, or lived in a huge house like he did. And I was terrified of his dogs. He liked kids and he was a very funny, wonderful person with me. He taught me to swim. He even wanted me to come and live with him and Jacqueline for a while because he wanted to paint me. But my parents didn’t allow that because they thought that it was too much being dragged back and forth between France and Norway. So that never happened, unfortunately.

But Picasso was a huge presence in our life up until he died in 1973. I remember my father was in the south of France at the time. They were working on what was to be the world’s largest concrete sculpture, and my father was down there to show him the plans and discuss where to put it. They were supposed to meet on Monday morning. On the Sunday my father was sitting in a coffee bar in Cannes and heard that Picasso was dead. That last sculpture was never made.