On 27 March, in a scene of great dramatic power, at dusk, under driving rain, and facing the vast emptiness of St Peter’s Square, Pope Francis blessed Rome and the world and prayed for an end to the pandemic. It was then that he said the words which have been much quoted since, “Our planet is gravely ill. Without hesitation, we have carried on, believing that we will remain healthy for ever in a world that is sick”.

Against the columns behind him were two works of art, which for the purposes of this event were not works of art as we understand them, but images believed to have strong protective power. We were being shown them in the same spirit in which they were made centuries ago, and with all the traditions that have accumulated around them, instead of the de-sacralised spirit in which we experience religious images as art historians or tourists.

On the right there was the large icon known as Maria Salus Populi Romani (Mary salvation of the Roman people), believed for centuries to have been painted by St Luke the Evangelist and brought from Jerusalem. It normally hangs in the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in its own sumptuous baroque chapel surrounded by a triumph of angels.

The icon known as Mary, Salvation of the Roman People

Its modern, scientific, art history is this. It is a Virgin and Child painted on cloth applied to panels of limewood, with a frame of ash. When it was restored by Vatican conservators in 2017, radio-carbon analysis dated the wood with 80% certainty to some time between the late 9th and early 11th centuries. It belongs to a particular type of Byzantine Madonna and Child known as hodegetria (she who shows the way), but in its actual paintwork, it is close to pictures known to have been made in Rome in the 11th and 12th centuries. So much for it having been painted by St Luke.

Its long devotional history, on the other hand, is this. From medieval times, it was Rome’s most venerated image of Mary, considered from the 15th century at least to have miraculous powers. In 1571, Pope Pius V prayed in front of it before the decisive victory over the Turks at Lepanto, and in 1834 it was invoked by the pope during the cholera epidemic.

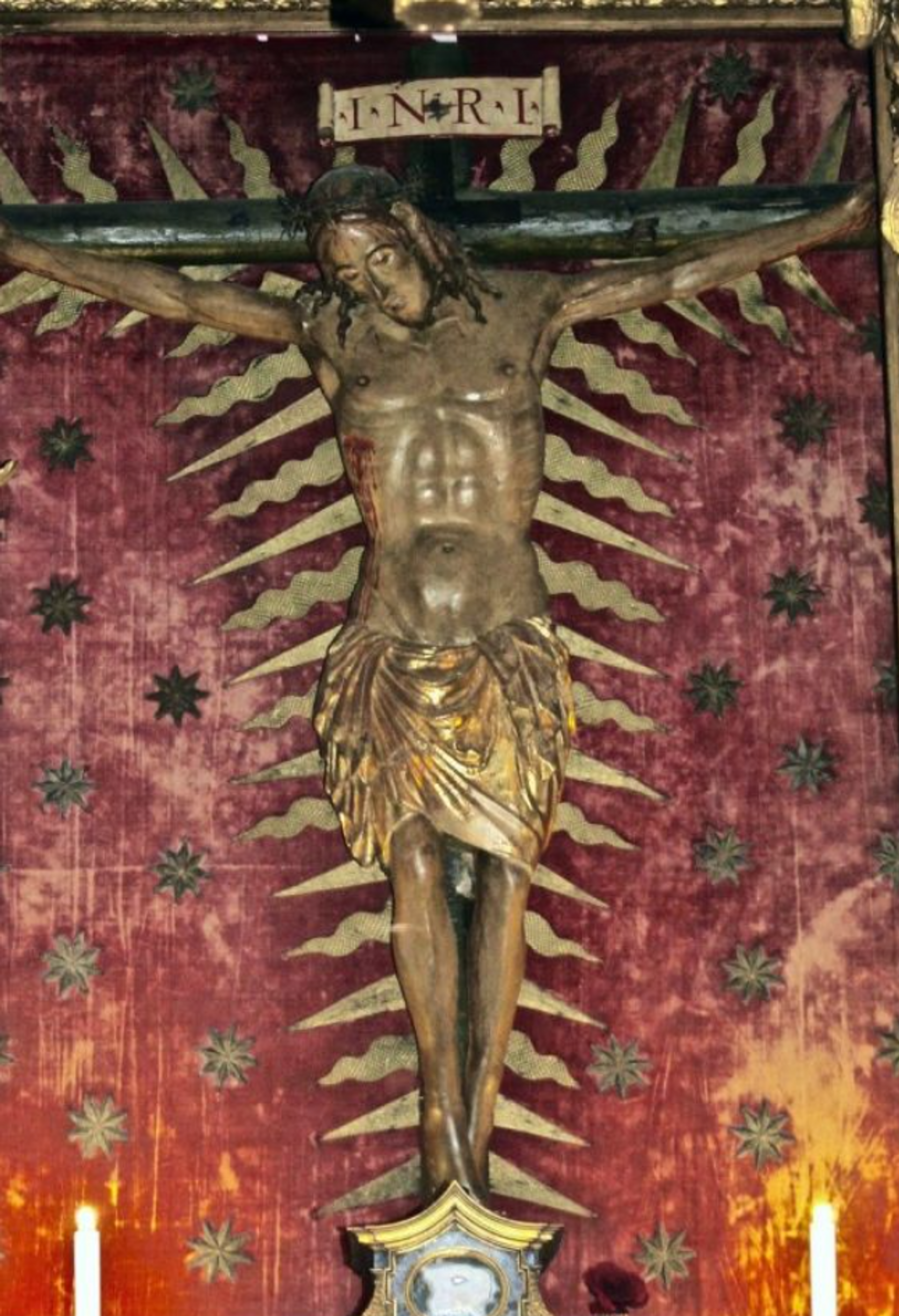

The crucifix on the left-hand column of St Peter’s was from the church of San Marcello in the Via del Corso, and in art-historical term it is rather ordinary, one of hundreds of workmanlike crucifixes, sculptor unknowable, dated tentatively to the late 14th century. The only interesting thing about it is that it is very like another, slightly older crucifix in San Lorenzo in Damaso, which may have been brought to Rome from northern Europe.

The plague crucifix in the church of San Marcello, Rome

Its devotional history begins in 1519 when it escapes a fire that destroys the church, since rebuilt, and its thaumaturgical reputation blossoms when the plague infected Rome in 1522. It was carried in procession around the city for 16 days, at the end of which the disease died down. Since then it has been processed solemnly from its church to St Peter’s every year on Thursday in Holy Week, before Easter.

The pope paused to pray in front of both of them. Does this mean that he believes they are capable of bringing about a miracle? Certainly not. The Church is quite clear that attributing divine qualities to an image is idolatry. In the 4th century, the theologian and Doctor of the Church, Basil of Caesarea, put it very sensibly: "If I point to a statue of Caesar and ask you, 'Who is that?', your answer would be, 'It is Caesar.' When you say that, you do not mean the stone itself is Caesar, but that the name and honour you ascribe to the statue passes over to the original, the archetype, Caesar himself.”

Thus, thus what the pope is doing is praying to God, directly and through the intercession of the Virgin Mary, as represented by the two works of art. A modern equivalent would be the way in which the US flag is folded with great reverence, which honours the country it symbolises, not the piece of cloth.

But the Catholic Church is ancient and broad, and while it does not actually encourage belief in the thaumaturgic power of images, where this survives as a focus of local devotion, it is tolerated, and this crucifix and Maria Salus Populi Romani are a beloved part of Rome’s traditions, which is why they were chosen to be with the pope last month and throughout the Holy Week celebrations.

What is interesting in anthropological terms is that the great religious works of art very rarely become objects of popular devotion; no one lays votive offerings or scribbled petitions in front of Michelangelo’s sublime Pietà. Rather, it is the old, often strange or downright ugly pictures or statues to which legends and events have become attached, such as the Baby Jesus in Rome’s Santa Maria in Aracoeli, said to have been carved from an olive tree in the Garden of Gethsemane, and covered with modern and valuable ex-voto jewellery. This is not even the original, but a copy of a copy, the first version having been stolen in 1791 and the second, in 1994, but the juju has been passed on miraculously.