In November 2014, The Art Newspaper published an article by Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson called Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s urinal?

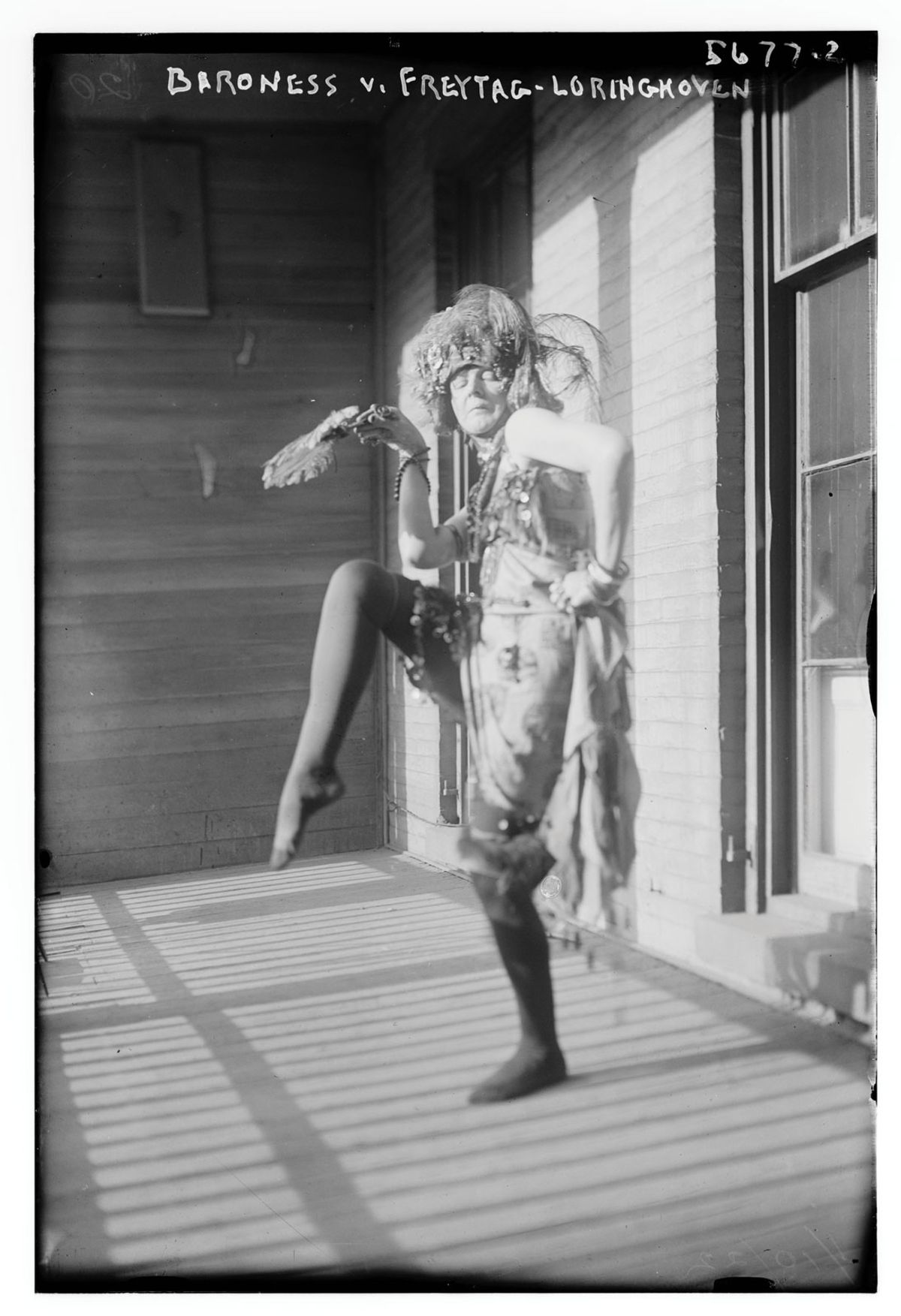

Their contention was that the artist and poet Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven was responsible for submitting the famous Fountain, an upturned urinal signed R. Mutt, to the Independents exhibition in New York in April 1917. These assertions appeared to confirm the worst suspicions concerning the art-world patriarchy, and so have become widely distributed on the internet.

This controversy was recently revived when, in October and December, two articles in Burlington Magazine, by Bradley Bailey and then by ourselves, refuted these assertions in great detail (an updated version of the latter and a summary of the facts, can be found here.

Spalding’s website continues to call Duchamp a thief and claims that “The Art World has been lying to us”: classic conspiracy theory rhetoric (note the capitals!)

Spalding and Thompson have never produced any evidence that connects the Baroness with Fountain, only interminable speculations about what might or could have occurred if their theories happened to be true. These speculations have been refuted or shown to be unproven in the articles mentioned, but they are all anyway irrelevant unless Spalding and Thompson can answer the only question that matters: “What evidence connects the Baroness to Fountain?”

If they cannot provide this evidence then their only honourable course of action is to admit they were wrong, or they must be presumed to be deluded. However, we recall the old saying: “Reasoning will never make a man correct an ill opinion, which by reasoning he never acquired.” We are not holding our breath!

• Dawn Ades, professor emeritus of art history and theory at the University of Essex

• Alastair Brotchie, proveditor of the Collège de 'Pataphysique in Paris

‘It’s the world’s first great feminist, anti-war artwork’

To answer Dawn Ades’s question briefly: all the evidence connects the urinal to Baroness Elsa and none to Duchamp, including the fact that he wrote at the time that he didn’t submit it [to the Independents exhibition] and that he couldn’t have acquired this urinal where he later claimed he did, because that New York firm didn’t stock this model. The internal evidence is, if possible, even stronger. The puns, the form, and the meaning relate it closely to Elsa’s other sculptures, particularly God.

The urinal is the world’s first great feminist, anti-war work of art.

• Julian Spalding, art critic, writer, broadcaster and a former curator

No grounds for Ades’s view

Interested readers should know that Dawn Ades’s assertions are ultimately grounded in the popular misconception that Marcel Duchamp was responsible for the urinal. What they will not learn from her criticism is that no evidence whatsoever either suggests or confirms that this was the case—for none survives, hence Ades’s failure to cite any. In fact, the only item of forensically weighty evidence comes from Duchamp’s own hand, in which he informed his sister Suzanne, two days after the urinal had been rejected, that not he but a “female friend” had been responsible.

Due diligence conducted on the history of the attribution to Duchamp that underpins Ades’s assumptions demonstrates that, far from it being made in April 1917, the first citation was by Georges Hugnet, in Cahiers d’Art in 1932. There, not a shred of evidence is offered in support of such claims that, for example, Duchamp actually had “entered a porcelain urinal with the title Fontaine”, or that Duchamp had “signed it R Mutt”, for nowhere on the urinal, or the attached label, will you find Duchamp’s hand.

Nor did Hugnet provide evidence for Duchamp having done so “in order to test the impartiality of the jury” (not least since there was no jury to display any impartiality); or that, in so doing, “Duchamp had wished to signify his disgust for art and his complete admiration for ready-made objects”, since he had neither submitted, nor therefore, signified, anything.

But Hugnet’s unsubstantiated attribution would nevertheless be insinuated unalloyed into the master narrative by André Breton, equally unencumbered by any obligations to factual accuracy, in 1935, in Minotaure, and the rest is art history, courtesy of the March 1945 issue of View Magazine.

Ades makes much of Bradley Bailey’s research published in the October 2019 issue of the Burlington Magazine, in which he presents the theory that the “female friend” who submitted the urinal to the Independents exhibition was the author and Duchamp’s friend, Louise Norton.

What Bailey fails to reconcile is that, although the address on the label attached to the urinal was that of Norton, neither it, the name, nor the title of the work, is written in her hand, suggesting that Bailey has introduced into the practice of provenance the innovative concept that the absence of a signature from a work of art proves its authorship.

Three other individuals resided at that address at the time, all of whom were equally qualified to have been capable of delivering the urinal to the Grand Central Palace on Easter Monday 1917.

Further, Ades has persisted with her belief that Duchamp’s sister Suzanne, a Red Cross nurse in Paris, had put it about the New York art scene that Duchamp was not responsible for the work, an idea that Julian Spalding and I have cast doubt on. In the December issue of the Burlington Magazine, Ades wrote: “As for the assertion that the artist (rather than ‘the nurse’) Suzanne Duchamp was not in touch with the New York art scene, her partner was then Jean Crotti… who in 1916 had shared a studio with Duchamp in New York, where Crotti lived for several years. He was on amiable terms with nearly every person involved with the exhibition.”

The following facts contextualise the situation. Suzanne was a nice petit bourgeois provincial, with no profession, who had enrolled in the Red Cross at her own expense to do her bit for the Union Sacrée, becoming a nurse at the Hospital for Blind Children in Paris. She had no medical experience, training or qualifications.

Given the logistics of Ades’s proposition, the entire suggestion is quite ridiculous. It assumes that Suzanne had contacts in New York on whose confidence she could rely. But of course no evidence suggests that any such thing ever happened; there is no record that anybody suspected or accused Duchamp of having anything to do with the urinal, or that anybody encouraged anybody else to believe that Duchamp had either been responsible or not.

Everybody believed that “R. Mutt” was just another nobody who had taken the opportunity, usually denied nobodies, to show his work. Whilst some doubted his sincerity, nobody doubted his corporeality.

In short, it’s bollocks: the ridiculous fiction was invented in the 1960s when Duchamp was interviewed by Otto Hahn and Pierre Cabanne. It was elaborated into what Ades adheres to by William Camfield, Thierry de Duve and Francis M Naumann, all of whom had confused the “no jury” rule with a carte blanche that would allow anybody to show anything. They didn’t bother to read the publicity issued by the society that made it explicit that only members could show. Ades fails to identify anybody with whom Suzanne is known to have enjoyed any contact in New York during this period, citing no evidence that suggests any campaign to protect Duchamp’s alleged anonymity was ever conducted, which is hardly surprising since, not having been responsible for the urinal, he had no anonymity to protect.

• Glyn Thompson, independent scholar, curator and writer

Urinal row rages on

Julian Spalding and Glyn Thompson have replied as expected to our letter that Marcel Duchamp stole his readymade Fountain from the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Spalding was cursory, and the only “evidence” he presented was his own opinion, which merits no further comment. Thompson’s reply was prolix; where not irrelevant, it consisted of arguments we have already refuted, and refutations of arguments we never made. His assertions are easily disproved.

Last December we published a detailed critique of Spalding and Thompson’s accusations in the Burlington Magazine and this—along with our refutations of Thompson’s reply to our letter in The Art Newspaper— can be consulted here. Spalding and Thompson have so far refused to respond to our original article yet continue with the same arguments.

Here we wish to concentrate on the real crux of the matter. We have reduced this argument to two questions, which Spalding and Thompson should be able easily to answer if their accounts are correct.

First, setting aside what Duchamp did or didn’t do, what facts connect the baroness to Fountain? So far as we can see, the only connection cited by Spalding and Thompson or by Irene Gammel, who wrote a biography of the baroness, is that an unknown journalist, and not exactly a “serious” one, and then some other journalists, wrote that Richard Mutt lived in the same city as her, Philadelphia. Is that it?

Second, almost the only undisputed fact in this affair is that the address of Duchamp’s friend Louise Norton was on the submission label attached to Fountain: this fact is agreed by Gammel, by Spalding and Thompson, and by those who accept Duchamp’s account. Thus, Louise Norton is the only person whose pivotal role as go-between is acknowledged in all three versions of these events, and because of this role, she had to know what actually happened. In a text recently discovered by the art historian Bradley Bailey, Norton wrote of Duchamp: “To test the bona fides of the hanging committee he sent in a porcelain urinal which he titled, Fountain by R. Mutt. The committee promptly threw it out and Marcel very angry promptly resigned.” This statement on its own proves that Spalding and Thompson are wrong. Is this not the case?

It should be noted, however, that this statement was not available to Gammel in 2002 when she published her biography of the baroness, which is the source of this rumour against Duchamp. So, since the welcome aim of restoring agency to forgotten and overlooked women artists and poets is not served by misinformation, now is perhaps the appropriate moment for her to comment on this controversy?

Dawn Ades, professor emeritus of art history and theory at the University of Essex Alastair Brotchie, proveditor of the Collège de ’Pataphysique, Paris

Characteristically Duchamp

I laughed out loud at the blustering responses you printed by Messrs Spalding and Thompson to the eminently reasonable rebuttal of their arguments about Duchamp’s Fountain sent in by Dawn Ades and Alastair Brotchie. What a pair of clowns we have in Spalding and Thompson.

The best and surest evidence that it was Marcel Duchamp and not Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven who came up with Fountain is—surprise, surprise—the visual evidence. In a nutshell, Fountain looks EXACTLY like a Duchamp and NOTHING like an Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Everything about Fountain, from its punning fake signature to its readymade misogyny, screams Duchamp. Spalding and Thompson need a visit to Specsavers if they cannot see that. It’s even included among Duchamp’s miniature life works in La Boîte-en-valise, for heaven’s sake.

Fountain’s real crime is not that it was made by someone else but that it was a graceless piece of sexist jokiness by an artist with an impeccable track record in exactly that. Have you seen the cartoons he made before he took up painting? Have you seen Étant donnés?

The vagueness of Fountain’s provenance is proof only of its embarrassing origins. Not even Duchamp was immediately keen to claim the creation of a giant porcelain vagina.

• Waldemar Januszczak, art critic for the Sunday Times, London

Mud-slinging about ‘the most influential art work of the 20th century’

The dispute, initiated by Julian Spalding’s and Glyn Thompson’s article Did Marcel Duchamp steal Elsa’s Urinal?, about the authorship of Fountain, Duchamp’s most notorious readymade, seems to have reached the stage of mud-slinging, if judged according to its latest instance in The Art Newspaper issue of February 2020. The term applies because the battle’s issue has been blurred: Spalding/Thompson’s article was targeted against “the art world as a whole” because of its refusal to acknowledge the ‘fact’ that Duchamp had stolen the idea of Fountain. But in its present stage, the dispute has focused on whether he had stolen it from one specific person: Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Dawn Ades, professor emeritus of art history and theory at the University of Essex and opponent in this dispute, in her response published on atlaspress.co.uk, puts a lot of effort in disproving any connection between Duchamp and the Baroness in order to invalidate Spalding/Thompson’s conclusion that Duchamp was a thief. But whether he stole it, and if so from whom is hardly relevant as to the elephant in the room of the original article, which casts serious doubt on Duchamp’s authorship of the most influential art work of the 20th century (according to a poll of 500 art experts conducted by BBC News in 2004), the authors’ fundamental piece of evidence being a letter in which Duchamp wrote to his sister, just two days after Fountain had been rejected by the Society of Independent Artists: “A female friend of mine, using a male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, submitted a porcelain urinal as a sculpture.” Ades tries to dispel this strong evidence against Duchamp’s authorship by suggesting that it was a strategic lie. But why should Duchamp lie to his sister in Paris about his authorship?

Whoever submitted the porcelain urinal, it was not Duchamp, and about how far Duchamp originally was involved we can only speculate. What emerges from the dispute rather shows the features of a collaborative jest involving Duchamp and his female friend, but also Stieglitz, Arensberg and Picabia, who according to a source cited by Ades made the first connection between the urinal and readymades in 1919; and here the deeper root of the dispute’s virulence may be found: if Duchamp’s authorship of Fountain is qualified, his historical status as the inventor of the readymade might be as well. Duchamp of course made other readymades, but he defined them as “three-dimensional word plays” or puns, having nothing to do with art. This is quite different from the ‘readymade’ definition that has entered mainstream orthodoxy as the breakdown of the boundaries between art and everyday life, the master narrative upon which contemporary art practice largely depends—from all sorts of appropriation art to today’s confusion between art and cultural and/or luxury industry—that of an everyday object which is promoted to the status of art through simple choice by an artist. This definition can be traced back to André Breton’s ‘Phare de la Mariée’, published in Minotaure in 1935. Nevertheless, it is officially attributed to Duchamp to the extent that the Duchamp entry in the Encyclopedia Britannica begins with the attribution’s implication: “French artist who broke down the boundaries between works of art and everyday objects.” This definition’s persistence is the more astounding as a common sensical second thought should suffice to reveal its inconsistency: for an everyday object to become art a change of function is required, from a practical to a symbolic one that is, and in order to signal this it needs to cross precisely that border which it is supposed to break down; in short: without that border there simply wouldn’t be a ‘readymade’, according to the orthodox definition, at least.

Understandably, there is strong resistance to confront this flagrant inconsistency, as it would require reconsidering the theoretical underpinning of a major part of contemporary art since the 1960s, which might explain the shift of focus in the course of the dispute. Ironically, it is precisely that shift that betrays the crossing of that border: we are clearly in the art world, because nowhere else the issue of individual authorship is more important.

• Franz Kaiser, professor of art history at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg, Germany