“There are no artists in the GDR, all of them left … The GDR artists are just cheerleaders for the regime, they are simply arseholes,” said the artist Georg Baselitz in 1990 after the reunification of communist East Germany (GDR) with West Germany.

This famous statement in the magazine Art was pretty much what the West German art establishment thought too, condemning East German artists to decades of obscurity. West Germans took over many of the top museum jobs in the former GDR, put the contemporary collections in store and showed West German art instead.

The paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and photographs commissioned by GDR authorities were also removed from public buildings, the parliament, town halls, universities, holiday camps and youth clubs. For a quarter of a century, 23,000 works from the states of Berlin, Brandenburg and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania were stored in a warehouse near Burg Beeskow 95km from Berlin, out of sight and under inadequate climatic conditions.

It took until 2015 for a full inventory to begin to be made, and now the art has a new, temperature-controlled home in a converted school. “For the first time we can look after it properly,” says the archive’s director, Florentine Nadolni, “Most importantly, at last we can make it visible!”

This new visible storage was enabled by a €300,000 grant from Invest Ost, a programme for cultural institutions in eastern Germany. Since opening in May, it has welcomed more than 1,000 visitors on guided tours. The visitors have ranged from East Germans keen to see the art of their childhood, to curators from Singapore and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It is a sign, Nadolni says, that perceptions towards GDR art are changing. Her colleague Angelika Weissbach, a specialist in the subject, adds: “There is a generation who see it with more distance, less emotion.”

We have too often made the mistake of looking at the art of [GDR] from a political perspective only

For Nadolni and Weissbach, the revival in interest has meant they are busy. They aim to digitalise the collection and make it available online, and have worked on a current show in the regional parliament of Brandenburg in Potsdam, which is running until 11 December. Titled Arbeit, Arbeit, Arbeit (work, work, work), it is about the idealised image of workers and the realities of day-to-day work in the GDR.

Much of what is in the Kunstarchiv Beeskow is indeed true to the party line of the communist regime. Weissbach draws out one rack to reveal a section of an enormous 1979 polyptych, Proletarier aller Länder vereinigt Euch (Workers of the world, unite!), by Willi Sitte, a committed socialist and the long-serving president of East Germany’s artists’ association. Depicting portraits of Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht and Marx and Engels, it once adorned the foyer of the now demolished Palast der Republik in Berlin. A few racks away, however, is an early painting of a Leipzig street scene by Neo Rauch.

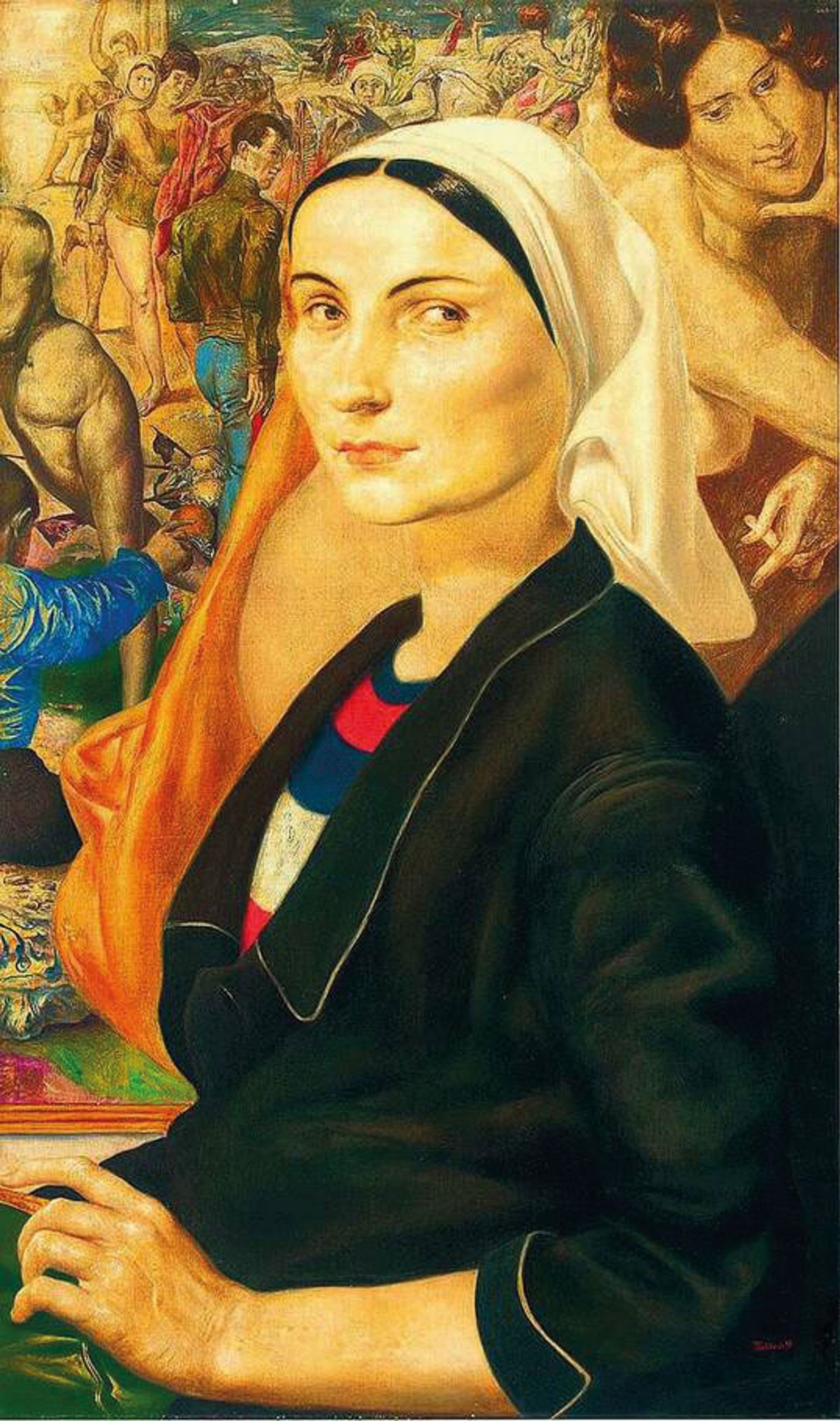

Werner Tübke's Portrait Gisela Schulz (1969) fetched €134,000 in May 2019 © Kunsthandel Lehr, VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2019

What is happening at Beeskow castle is part of a wider rehabilitation of GDR art, both by institutions and by the market. While in 1994 the director of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin was severely criticised for showing works by GDR artists, there were two major exhibitions in Germany last year. In Leipzig, Point of No Return explored art in the former GDR before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, while in Düsseldorf, the Kunstpalast held a large exhibition called Utopie und Untergang (utopia and downfall), both about the GDR artists who worked for the regime—some of the most famous—and those who resisted it.

A prominent collector of GDR art is the West German billionaire digital entrepreneur Hasso Plattner, who held an exhibition of it in 2017 in the Barberini palace in Potsdam and is setting up a museum for his collection in a nearby building, which is due to open in 2021.

The ideological objection to those who worked within the regime has largely died down because people today have grown up without the fear of communism but are curious about what happened between the end of the Second World War and unification in 1990. In Los Angeles, the collector Justin Jampol, who was born in 1978, has even founded the Wende Museum (wende—turning point—is a German term for the unification), dedicated entirely to the material culture of the GDR, from its curtain fabrics to its unsophisticated pornography.

We are also aesthetically more eclectic and less doctrinaire today. Art does not have to establish its moral credentials as an opposition force anymore; abstract and conceptual art is good, but so is figuration, and the GDR, with its four rigorously traditional art academies, certainly knew how to produce good figurative painters.

Willi Sitte's Comedians (1954-63) sold for €32,000 in 2006

Fifteen years ago, the post-unification New Leipzig painters such as Rauch enjoyed considerable success in the West, and now the ever-hungry market is ready to consume their more solidly communist predecessors such as Walter Tübke, Wolfgang Mattheuer and Bernhard Heisig. On 7 December, at Ketterer Kunst in Munich, a painting of 1978 by Mattheuer, The Fall of Icarus II, fetched $213,250 (including 25% buyer’s premium). It carried an estimate of $33,000.

In his remarks at the opening of the Utopie und Untergang exhibition last year, the German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier said: “From the western German side, we have perhaps too often made the mistake in the past of looking at the art of East Germany from a political perspective only.”

That is easy to say now that 30 years have elapsed and the political heat has gone out of the matter. The tougher question is why the art of the GDR was subject to censure for so long when its literature was not, a point raised by Ulrich Greiner of Die Zeit newspaper in 1994 during the row over the Neue Nationalgalerie’s showing of GDR art. A lot can be explained by the intolerant academicism of the contemporary art movement in the West—“This is art, while this is not art”—combined with its sense of moral superiority when faced with party collaborators, which conveniently forgets the collaboration demanded by the art market in the West.

• The federally supported site www.bildatlas-ddr-kunst.de lists 20,400 GDR works of art from 1945-90 held in 165 collections—in museums, businesses, stores and private institutions—with biographies of the artists