The tension between the art world’s traditional secretiveness and today’s desire to share data spilled out in a question at the inaugural meeting of the International Catalogue Raisonné Association at Christie’s London in November. “If you let people know which works by artists are ‘location unknown’, fakers may supply the missing work,” said one attendee.

Elizabeth Gorayeb, the executive director of the New York-based Wildenstein-Plattner Institute (WPI), answered: “There are always going to be forgers, but there will also be astute forensic conservators who will be able to unmask their forgery.” In short, the overall gain in knowledge from openness will deal with such individual problems.

The WPI is the product of an alliance in 2016 between the art dealer Guy Wildenstein and Hasso Plattner, the philanthropic German software billionaire and collector of Impressionist art, Wildenstein’s core specialism.

The non-profit WPI, founded in 2017, is throwing open the legendary Wildenstein archives accumulated since Georges Wildenstein published the firm’s first catalogue raisonné in 1922.

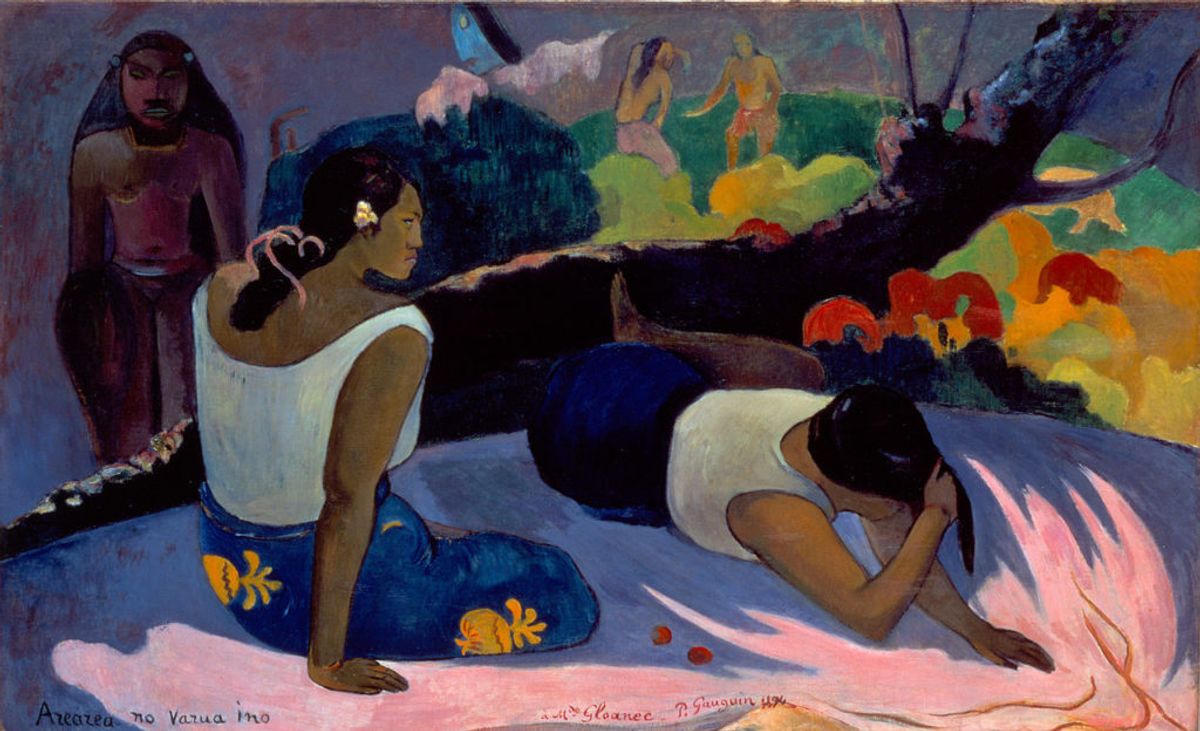

All material relating to the following artists has been donated by the Wildenstein Institute to the WPI: Jean Béraud, Paul Gauguin, Camille Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Édouard Manet, Albert Marquet, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Kees Van Dongen, Maurice de Vlaminck and Édouard Vuillard. These archives will be digitised, categorised and cross-referenced according to the most sophisticated data-handling systems, while a team in Berlin is developing bespoke software for the project.

So, 100 years of annotated sale catalogues, letters and notes are being digitised to be made available to the public for free on the WPI’s platform.

The Hasso Plattner Institute is working on OCR (optical character recognition) software that will not only recognise when a sale catalogue has been annotated but will be able to distinguish between hands and “read” the writing. The WPI will share its data with other institutions such as the Getty Institute, with which it is already collaborating, and it is working towards applying existing standardisations of the way in which works of art are described so that cross-searching of data becomes easier. It has chosen to be in New York because it is the centre of the art market, but also because copyright law in the US allows “fair use” publication of copyright material if it is for educational purposes. “You have to activate your archive,” Gorayeb says.

The WPI has completed the catalogue raisonné of Jasper Johns and is compiling one on Tom Wesselmann. It hopes to collaborate with other archives but will not be buying any; nor will the WPI authenticate works, the remit of the Wildenstein Institute. Gorayeb says that the WPI believes catalogues raisonnés should be digital and open-ended so amendments can be made easily, but also so that they can incorporate multiple meta-data, which will allow searches to be made on themes that might become as hot in the future as the kind of questions we ask today: for example, how many works by women artists under the age of 40 did Wildenstein sell in the 1920s?