When the art collectors Aaron and Barbara Levine came across a dark-green imitation leather box at New York’s Sean Kelly Gallery in the early 2000s, little did they know it would land their collection a home on the National Mall. The box was Marcel Duchamp’s La boîte-en-valise (1935-41/1963), an extraordinary compendium of miniature handmade reproductions of 68 of his own works. This weekend, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, celebrates the 18-year obsession that acquisition sparked with Marcel Duchamp: the Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection, the first stage of a two-part exhibition on the life and works of the French artist.

The Levines have bequeathed to the museum, upon their death, more than 35 works by Duchamp: a career-spanning set of works on paper, readymades, compendiums and other pieces. The gift is a coup for the Hirshhorn, with the chairman Daniel Sallick comparing it to “the [Washington] Wizards getting LeBron James”. For the senior curator Evelyn Hankins, the Levines have quite simply “amassed one of the most important recent collections of Duchamp.”

Marcel Duchamp Rotoreliefs (Optical Disks) (1935/65) Photo: Cathy Carver; © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019

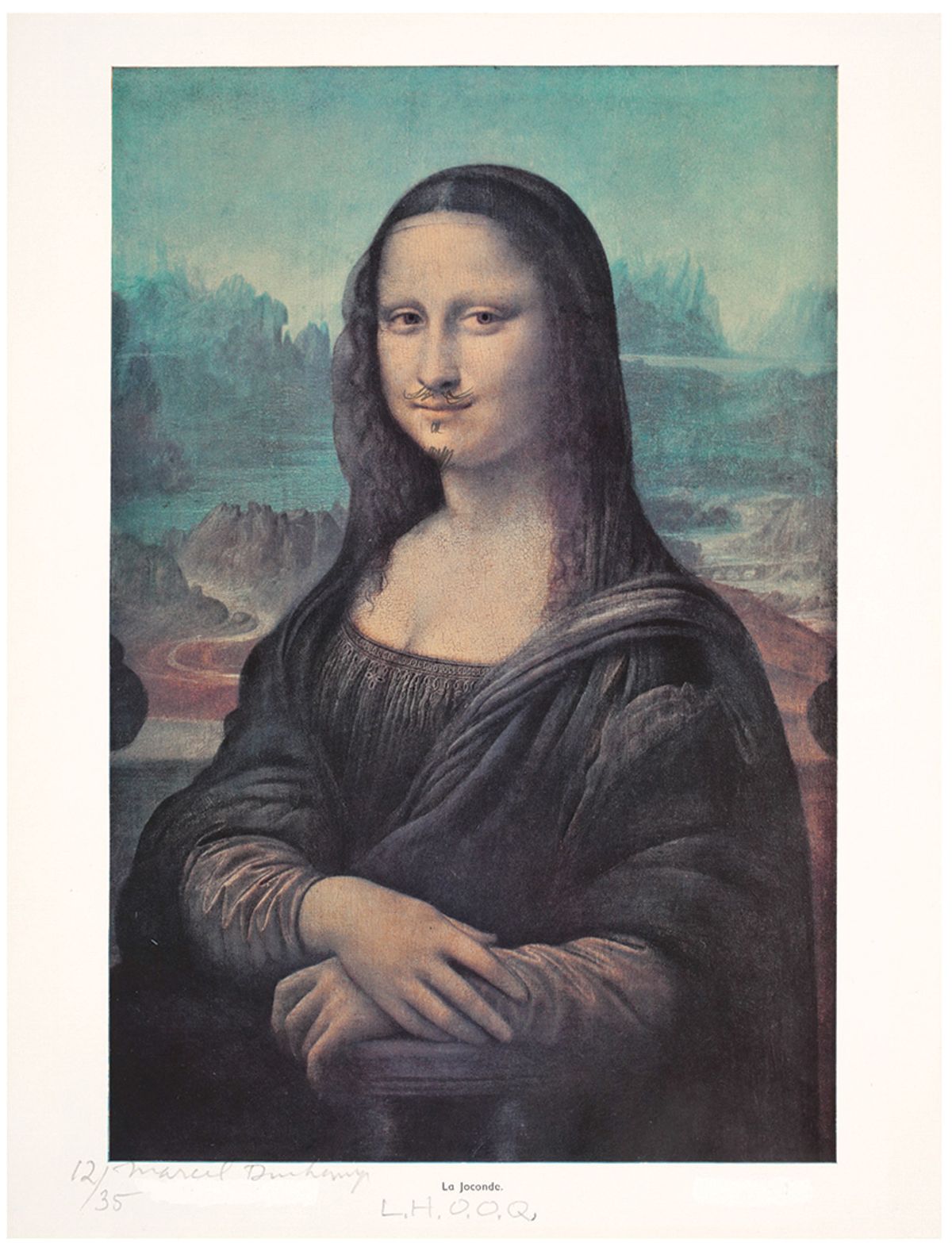

The exhibition will be a primer of the artist’s career, starting with an early drawing of his sister, from 1908, and following his output through to the 1960s. Among the pieces on show will be several readymades, such as Hat Rack (1917/64), Comb (1916/64) and Why Not Sneeze? (1921/64), and two versions of Duchamp’s moustachioed Mona Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q. There will also be a number of works that he made with Man Ray, including Dust Breeding (1920) and Anemic Cinema (1926), the experimental film in which they activated Rotoreliefs.

There will be an interactive element to the show too, with visitors being invited to play on two chess sets that will be installed in a nod to the famous Julian Wasser photograph of the artist engrossed in a game with his naked opponent, the writer Eve Babitz. Several portraits of Duchamp, by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Diane Arbus will also feature.

Marcel Duchamp's La boîte-en-valise (1935-41/1963) © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2019

For someone routinely hailed as the originator of contemporary art—the father of all who followed, as Aaron Levine puts it—Duchamp’s works can nonetheless seem quite reserved. “There’s a modesty to them,” says Hankins. For viewers steeped in what she dubs an age of Instagram and spectacle, this might be a challenge. For the Levines, though, these works are objects to marvel at. “Did you know that a urinal can be a thing of beauty? Can you imagine a hat rack glowing?”

• Marcel Duchamp: the Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC, 9 November-12 October 2020