Nando’s restaurant in Bristol, UK, with a work by Patrick Bongoy (black and red, centre) © Nando's

The world’s largest collection of South African contemporary art hides in plain sight. Over 22,000 works are hung on the walls of Nando’s, the come-one, come-all chain of chicken restaurants better known for its peri-peri than its pentimenti. With around 1,300 outlets worldwide, this is potentially the largest public viewing space for emerging South African art—if diners look up from that flame-grilled chicken.

The art initiative is the brainchild of Richard (Dick) Enthoven, the South African majority stakeholder in Nando’s, though publicly he takes a back seat. The family also has a private collection, consisting by all accounts of more ambitious and higher value contemporary South African works by more established artists. Unlike the particularly public Nando’s collection, the family’s holdings are very discreet.

The structure of the Enthoven-owned companies is complex. The family owns the insurance group Hollard, the Spier Wine Farm in Stellenbosch and the multinational Nando’s chain. All have their own art collections administered by the Spier Arts Trust, a Cape Town-based art consultancy which also runs various career development programmes for artists.

Joining the Chicken Run

The entry point of the Spier/Nando’s project is its Creative Block programme. Artists submit 10 works to be critiqued and, of around five applications per week, only 1% are accepted. Successful applicants are given a set of blank blocks to turn into works of art, then bring back to monthly selection—the best will be bought on the spot for a set sum, regardless of how well known the artist is. Many of these blocks hang in vibrant clusters on the walls of Nando’s worldwide, and Spier Art Trust holds around 5,000 of them at any one time (they retail at around £100 each). Regular Creative Block artists can progress to the Nando’s Artist Society (supporting 20 artists to create larger scale works) and, if their work is consistently up to scratch, they can graduate to the Chicken Run programme—the source of most of the work on the walls of Nando’s.

Diana Hyslop, based in the Bag Factory studios, the oldest in Johannesburg, has 151 works hanging in Nando’s around the world: “Dick Enthoven came here in 2010 and bought the first piece,” she says. “Every two months, Nando’s buy works. In South Africa, the market is not so huge and has gone right down at the moment with the economy, so this is a fantastic support.”

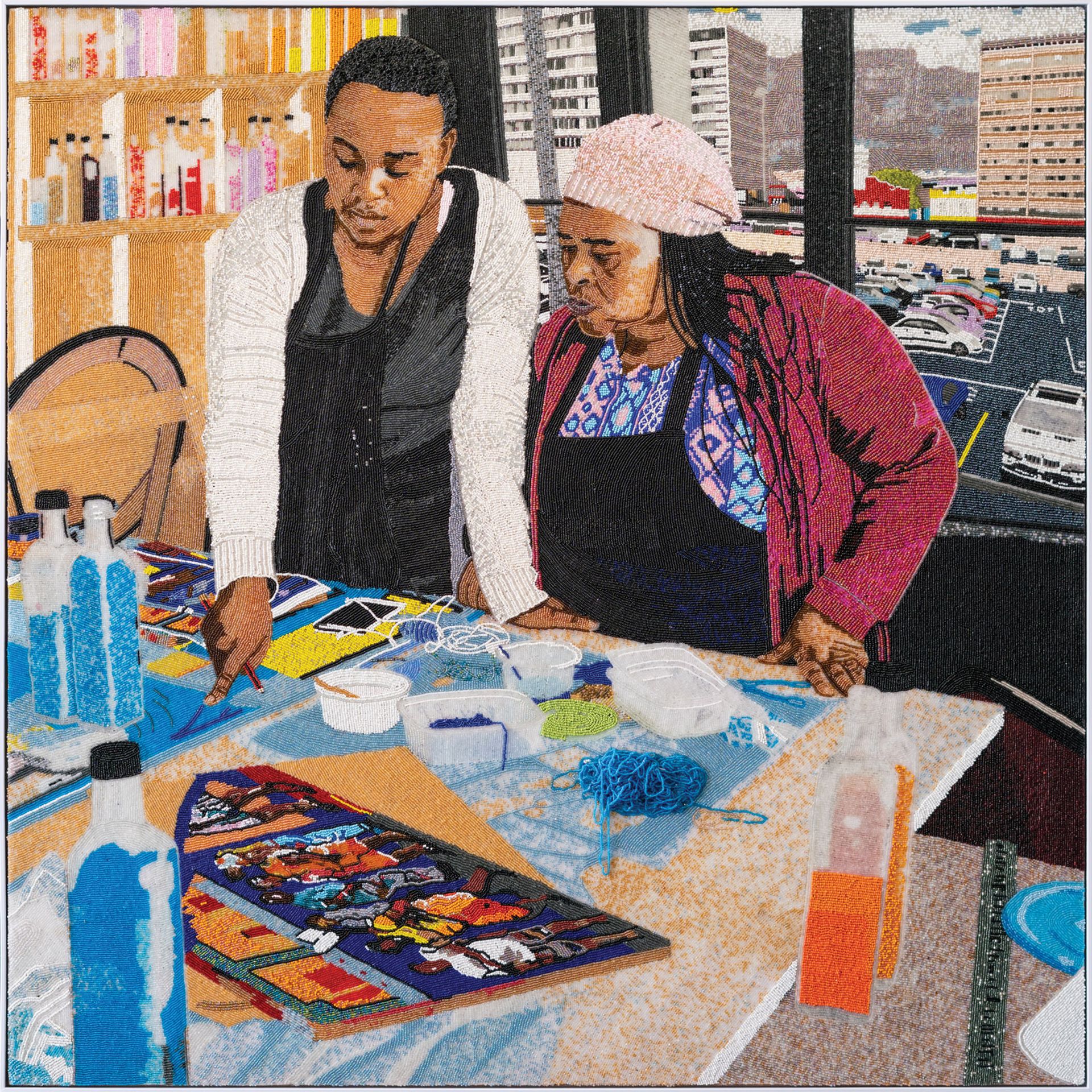

Qaqambile Bead Studio, Isisusa, Glass Seed Beads on Board Qaqambile Bead Studio and Nando’s

It is hard to think of a corporate art initiative on a similar scale, and perhaps it would not be possible (or so needed) in a country with a larger domestic art market. “Over the last four years, Spier Arts Trust has bought around £500,000 of art per annum, directly from artists through our programmes and from galleries,” says Mirna Wessels, the chief executive of the Spier Arts Trust. The trust then sells around 70% of these works—at cost price plus a 20% commission—to Nando’s, selected by the restaurant’s interior designers. Cultural sensitivities are taken even more seriously since some works were burned by Saudi Arabian customs. There is now a three-stage approval process, and only abstract works go to the Middle East.

Nando's serves a unique function in the South African arts ecosystem

South Africa’s racial tensions cannot be ignored and only last month a spate of xenophobic violence across Johannesburg prevented two Nigerian galleries from securing visas to exhibit at FNB Art Joburg. The attacks broke out in late August targeting African foreign nationals, who are being blamed for poverty, lack of jobs and social inequality in the country. Nando’s works with immigrant artists from countries such as Mozambique, Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Wessels says that while Spier Arts Trust does not “have a directive to purchase works according to any particular social or political theme…current issues that our country grapples with, such as xenophobia, are encountered in artworks when we engage with artists all the time.”

Joost Bosland, the director of Stevenson gallery in Cape Town, says: “Nando’s serves a unique function in the South African arts ecosystem” and its support “of artists that operate below the radar of the international art world provides an income, indirectly, to hundreds, if not thousands”. Most importantly, he adds, it lets artists practise without being forced to find other work. “That Nando’s achieves all of this through fair exchange, rather than handouts, makes it all the more remarkable.”

While Nando’s arts patronage is well known in South Africa, in the UK, Nando’s and art are rarely uttered in the same sentence. But this month, it returns as sponsor to the seventh 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair at Somerset House in London (3-6 October).

Each year, it selects four South African-based artists to exhibit —the selection, Wessels says, is designed to include a mix of race, gender, age and style, first by Spier Arts Trust, then Nando’s, before being submitted to Touria El Glaoui, 1:54’s founding director. The 2019 artists are: Nelsa Guambe from Mozambique, the Iranian-born, Cape Town-based Sepideh Mehraban; the Cape Town trio Qaqambile Bead Studio and Mxolisi Dolla Sapeta, a South African native.

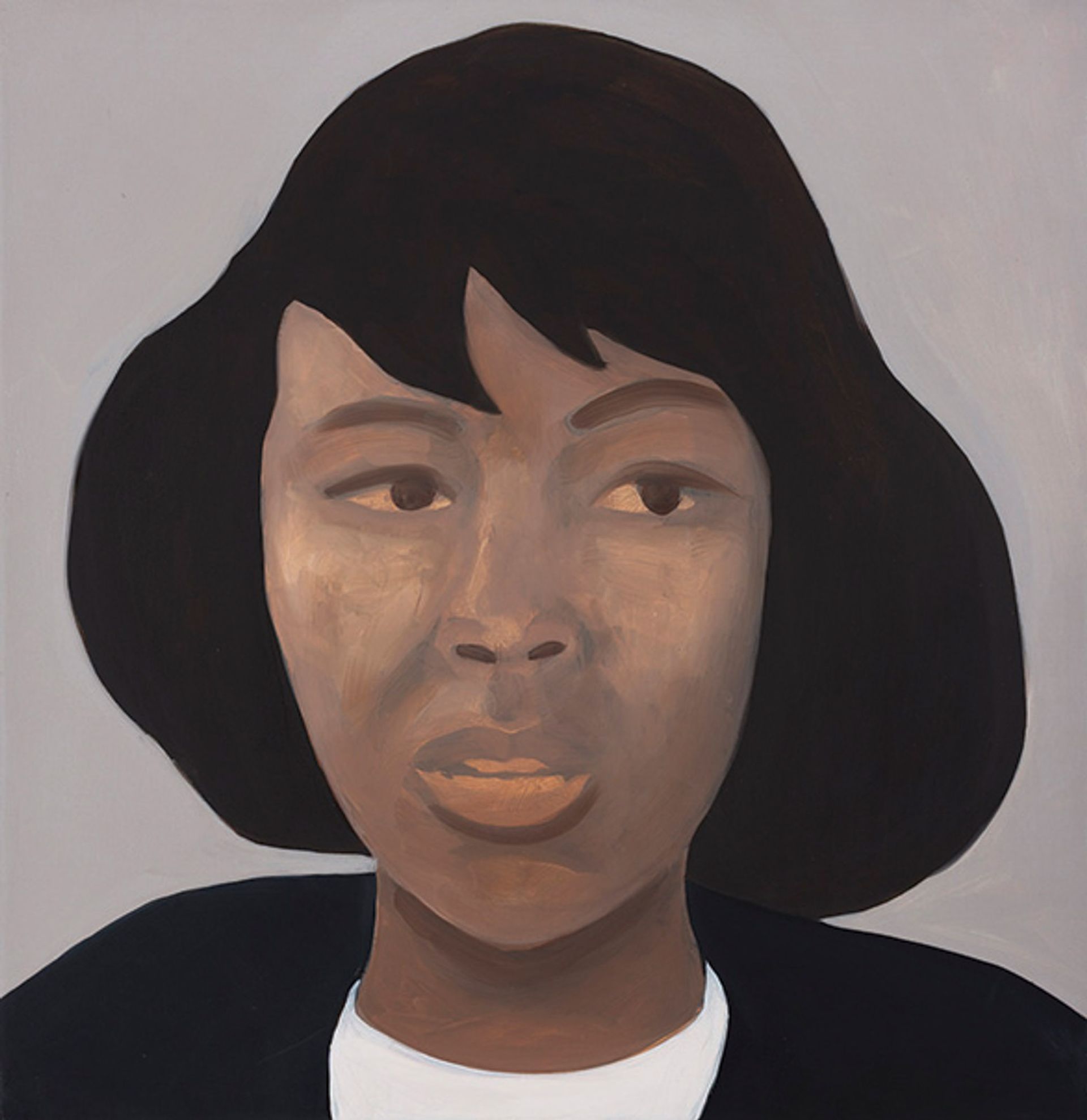

X (After Betty Shabazz, 2013) by Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi whose work hangs in Nando’s London HQ © Nando's

Supporting artists

Though the country’s economy is suffering, El Glaoui says this year will bring “the largest participation of South African artists and galleries [at 1:54]”, a rise she attributes in part to the new FNB Art Joburg in September, a 60% smaller reincarnation (18 galleries) of FNB Joburg Art Fair which has left some galleries in search of an autumn event.

Given the weakness of the rand and the emerging status of these artists, pricing is difficult, Wessels says: “We look at local South African gallery prices for their work then add about 20% more. If they have an international precedent, we look at that. Normally the works at 1:54 are priced between £700 and £2,000, the most expensive around £4,000.” All costs are paid for by Nando’s and, Wessels says, when works are sold, 100% of proceeds go to the artist. Anything that doesn’t sell is bought by Nando’s.

Last year at 1:54, Nando’s sold works by Patrick Bongoy, from the Democratic Republic of Congo but based in Cape Town. Bongoy creates sculptures and two-dimensional works using scrap rubber and is one of several Nando’s patronage artists whose works have appeared at auction recently, as African contemporary art becomes ever hotter and collectors seek out new names. Last October, Bongoy’s rubber and hessian sack sculpture, Revenants III, sold for £12,500 at Bonhams in London which Bongoy, speaking in his Cape Town studio, says was a big surprise. Another patronage artist, Mozambique-born Lizette Chirrime, has had a couple of works included in Piasa’s sales of contemporary African art in Paris.

The snobbery around being shown in a restaurant is really a western thing

Although Chirrime is one of the more commercially successful Nando’s patronage artists—and her work sold out when shown at 1:54 in 2016—she still teeters on the breadline. “I have this studio, materials, food and a roof over my head because of Nando’s,” Chirrime says in her studio in Cape Town. “Before it was really tough because the galleries in South Africa are not enough to support the artists.”

She adds: “Coming from Mozambique, there artists really starve and get involved in drugs. So, I left and came here as a single mum. I wouldn’t go back to Mozambique—things [artistically] are happening there but you have to hustle.”

Hanging art in restaurants is risky and, Wessels says, works do get damaged. Some are returned to South Africa for restoration, and in extreme cases, decommission. She adds: “When we acquire valuable works we notify the team to carefully consider placement.” Works loaned to museum exhibitions typically do not return to the restaurants. They are either kept in storage or hung in office areas. Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s Heroes series has travelled to shows in Paris and Warsaw and now hangs at Nando’s in Putney, its London headquarters. Mariane Ibrahim sold out of Nkosi’s work at Frieze New York in May.

While Nando’s support grassroots level is invaluable, tensions can arise if an artist reaches international standing. In the words of one dealer: “Being hung in a chicken restaurant is not great for an artist at a certain level.” But El Glaoui says: “From my discussions with artists, I honestly feel the snobbery around being shown in a restaurant is really a western thing. Nando’s is, essentially, one of the largest galleries in Europe in terms of the number of people who see their art.”

El Glaoui adds: “Maybe it becomes a problem if your career progresses and you start being shown by big galleries who have exclusivity contracts and might not think it a good idea if your work is shown in this context. But this is a timeline and Nando’s helps in the first steps.”

Context and class sway opinion and value in the art market and while being hung in, say, a Soho House restaurant is deemed acceptable, Nando’s is, well, a bit cheeky. But, snobbery aside, what is wrong with that?