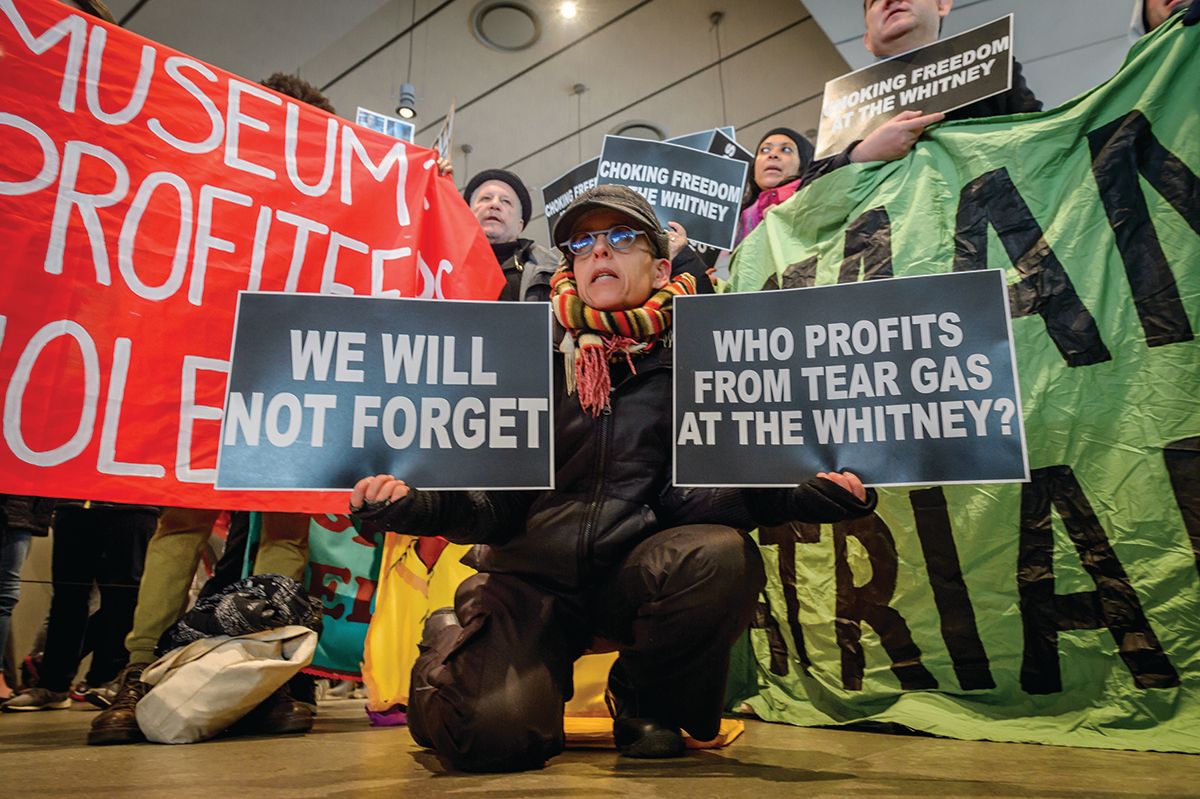

The departure of Warren Kanders as vice chairman of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York after prolonged protests is forcing US museums to publicly reckon with the make-up of their boards, once a mostly “inside-baseball” topic. More broadly, it is stirring worries that major donors may back away from making gifts for fear of facing controversy, museum leaders tell The Art Newspaper.

While US museums are largely dependent on private philanthropy, there are no uniform best-practice guidelines to help them in appointing board members or deciding what kind of trustees should be accepted or avoided. The Internal Revenue Service and state attorney generals monitor museums’ finances to make sure their funding is used for the “public good” rather than private enrichment, but museums are left to create their own internal procedures and codes of ethics, and professionals in the field do not see a consensus on the horizon.

“We have not developed a list of acceptable industries or investment strategies or unacceptable ones,” says Daniel Weiss, the president and chief executive of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “Rather, we take a look at individuals we’re working with in a holistic way in order to get a sense for who they are, what are their motivations for working with us, what their background is. It is not our goal to subject every donor to some kind of high-level litmus test to determine their suitability for the Metropolitan as a potential donor.

“In the case of working with particular individuals, it’s clear there is a line,” Weiss adds. “We would not accept donations from high-level visible criminals, or organisations that are egregious and violate our own values or mission,” he says. “At the same time, we are fundamentally supported by and we operate on the basis of philanthropy. That’s the American model.”

The decision to part ways with a patron is most often driven by legal concerns. In 2002, for instance, the collector and former chief executive of Tyco International, L. Dennis Kozlowski, was removed from the Whitney’s board after being indicted on charges of evading taxes on the purchase of works of art. He was eventually convicted of financial crimes. And after months of protests led by the artist Nan Goldin to expose the Sackler family’s ties to opioid sales—and several lawsuits filed by state governments—the Met recently announced it would suspend accepting gifts from family members who have been accused of profiting from the manufacture of OxyContin, which has allegedly helped fuel an addiction crisis in the US. But Safariland, the company run by Kanders, which manufactures tear gas cannisters that were fired on asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border, is not accused of breaking any laws.

“The scrutiny of museums’ funding sources is not going to go away and will likely intensify in the years ahead,” Laura Lott, the president and chief executive of the American Alliance of Museums, said in a statement. But the organisation does not offer any recommendations about what kind of funding institutions should avoid. Lott suggests “museums need to take steps and create transparent policies to ensure that current and future funding sources are diverse—not overly reliant on any single source—and consistent with their mission”.

The Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), which issues best practice guidelines on practices like deaccessioning works of art for the leaders of its 227 member museums across the US, has not issued guidelines for acceptable sources of funding. How a trustee makes their money can be perceived differently in different parts of the country, says the AAMD’s executive director, Christine Anagnos. For instance, support from the oil and gas industry might be more accepted in Texas than it is in California. “That’s where I say it’s bigger than just one moment and that the issues are complicated; the perspectives and communities are varied,” Anagnos says.

“It will be hard to find support derived entirely from sources beyond reproach”

Museums must also weigh up the ethical concerns about money they are accepting against the benefits it will foster. “Unless you are prepared to face real setbacks as an institution, it will be hard to find support derived entirely from sources beyond reproach,” says Maxwell Anderson, who served as the Whitney’s director from 1998 to 2003. During his tenure, for example, the museum received support from the tobacco giant Altria and even had a satellite exhibition space in the company’s New York headquarters. “Although it pained me to be complicit, I also knew that the money they provided was supporting our mission,” he says.

Adam Weinberg, the Whitney’s director, underscores how crucial philanthropy is to a museum’s mission. “Museums are fragile institutions that depend upon ongoing private support to fulfil a role in our society that is more essential now than ever,” he says in a statement, adding that while the museum is concerned and “carefully watching the situation”, there is no indication this support will not continue. “However, we would hate to see those who wish to support our efforts in bringing the work of American artists to a broad public become discouraged from doing so.”

And as museums have become more dependent on private philanthropy to keep operations running, there comes renewed public concern about the source of that wealth. “Museums understandably feel cornered,” says Andras Szanto, a consultant in cultural policy and philanthropy for the arts. “It’s hard to satisfy all concerns and constituencies. The crises involved now play out in the open, stoked by social media. And there’s no commonly accepted road map.”

The perils of portfolios

While controversies over accepting funds are mostly focused on the source of donors’ wealth and on corporate sponsorship, museums can also be faulted for their own investments. For example, the Museum of Modern Art in New York recently came under fire from protestors because its pension plan invests in for-profit prisons. “It may prove hypocritical to single out a donor who inherited wealth from a previous generation if the museum’s current portfolio isn’t purged of regressive investments,” Anderson says.

Weiss says: “Most mission-driven institutions think very carefully about how they invest. Many, for example, won’t invest in firearms companies, or organisations that they believe are inconsistent with their mission. At the same time—this is where it gets complicated—most of the endowments that we invest in, the funds are so co-mingled, you don’t know where the money is going. [Index funds] may very well have money in alcohol, or fossil fuels or weapons, and we don’t necessarily know that.

“We have a responsibility to work with donors that live responsibly within the laws and values of our society, and we have a responsibility to invest our resources in ways that are consistent with the humanitarian and public service mission that we have,” Weiss adds. “Our role is to enlighten the public around the values of fine arts, not to dictate what our policy ought to be around gun control or alcohol use or investment strategies. So it’s a secondary consideration—but it’s not an irrelevant one.”

What comes next?

Since Kanders’s resignation, questions have arisen about whether museums will become pickier about who is allowed to join their boards. But Anderson says: “I think the more serious consideration is, will people of means stay away?”

“It remains to be seen what the after-effect of the Kanders incident leads to,” Weiss says. “If one thinks about the great philanthropists who helped to create many institutions that we’re familiar with, these are people who had business practices that we would find objectionable today, from Andrew Carnegie to John Rockefeller. I think it’s a very healthy thing that people are talking about it, but I think it’s a dangerous thing to react too quickly, and begin to shut people down and close them out because they don’t conform to some particular idea people have about what’s acceptable.”

To draw wider audiences, museums are now aiming to be increasingly accessible, Weiss says. The Met has shifted its strategy on education, programming and exhibitions “because we want people to come, we want them to participate”, he says. “And with that there has come a higher level of scrutiny.”

“Each institution is obligated at any time to be able to speak compellingly about who it’s taking money from and why,” Weiss says. “I think the public has the right to ask that question, and we have an obligation to answer it.”