“Is the art world compatible with parenting?” That’s the question up for discussion in Between Production and Reproduction: Career and Motherhood in the Art World, a talk taking place at Art Basel as part of the fair’s Conversations programme. Whatever conclusion the panellists draw, motherhood is not a topic to be waded into lightly. As Victoria Siddall, the director of Frieze fairs and mother of one, says when it comes to having children: “There is no right or wrong way to do it.” Or indeed not to do it.

But the subject of being a good artist and a good mother is even more contentious. In 2014, Tracey Emin told Red magazine that she would not be making art if she were a mother, as she would refuse to compromise: “I would have been either 100% mother, or 100% artist.” She added: “There are good artists who have children, of course there are. They are called men. It’s hard for women.” Two years later, Marina Abramović told the German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel that she had three abortions, “because I was certain it would be a disaster for my work [to have children]. One only has limited energy in the body, and I would have had to divide it.” She added that it is “the reason why women aren’t as successful as men in the art world”.

But many disagree with these uncompromising views. In response to Abramović’s comments, Siddall says: “Obviously, she was talking from her own experience, but where it becomes very dangerous is when there is a dialogue that suggests you can’t be a good artist and have a child—it’s just not true.” As Siddall points out, many of the most successful living female artists are also mothers: Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville, Phyllida Barlow and Njideka Akunyili Crosby to name just a few.

Here, four women—a fair director, a dealer and two artists—explain how they make it work.

• Between Production and Reproduction: Career and Motherhood in the Art World, 13 June, 10-11.30am, Hall 1 auditorium, Messeplatz

Rana Begum Photo: Philip White

Rana Begum, artist

Two children, aged seven and ten

When Rana Begum decided to have children, she had to take the plunge: “There was no guarantee of me earning a good enough living. I just had to trust that I’d find a way to survive.” Begum’s path has not been easy—she suffered post-natal depression and got divorced just after her second child was born. She did not take maternity leave: “I knew I wouldn’t be able to stop working; it is just the way it is for artists.”

Her galleries were supportive: “Most [of the ones] I work with are run by women, so they’re careful about the pressure they’re putting me under.” However, she mentions two successful artists who’ve wanted to have children but worry about the impact it will have on their careers. “That’s not really a concern for men.”

Perhaps surprisingly for a single mother, Begum does numerous residencies—but only those that can accommodate children. Her son Jabril was only a year old during her Delfina Foundation residency in 2009 in Beirut, but Begum says the foundation “was amazing and managed to find a nursery that could take Jabril, and a flat big enough for us all”.

While having children has not changed her creative practice, it has enforced a better work-life balance, although she says: “It is difficult to a find a balance between creating/working and spending time with children, particularly in the creative industry as you are working more hours to survive financially.”

Dominique Lévy Photo: Zenith Richards

Dominique Lévy, art dealer

Two children, aged nine and 16

Dominique Lévy made the decision to have children on 11 September 2001. “I was in Tribeca and saw people jumping from the Twin Towers,” she says. “Then I ran north and jumped on a bus full of kids being removed from school. They all looked so scared. That day, I decided: I’m going to have a child.”

At the time, Lévy was running Christie’s private sales department in New York. “I really felt that when I got pregnant, I was pushed aside—maybe wrongly so. But I left almost immediately after giving birth.” It was hard, she says: “I couldn’t get my US visa renewed [Lévy is Swiss], and I was a young mother setting up a business.”

Her family situation, she says, is unconventional—Lévy recently separated from her partner of 18 years, the film producer Dorothy Berwin, with whom she is raising her two sons, and their father is an old friend of Lévy’s. Both, she says, remain “very involved in the kids’ lives”.

Difficulties arise “when a school play clashes with an auction, or a client is in town at the same time as a parent-teacher meeting,” but, Lévy says, “that is when being in a partnership is great because I can say, ‘Brett [Gorvy, her business partner], you know what, I have to go.’”

Lévy travels frequently, but keeps trips short and always takes her youngest son to school. “It’s hard to be a mother and have a career. It’s much easier for a man,” she says. “Any of the big guys can jump on a plane at a moment’s notice because they have their wives at home looking after the children. I cannot.”

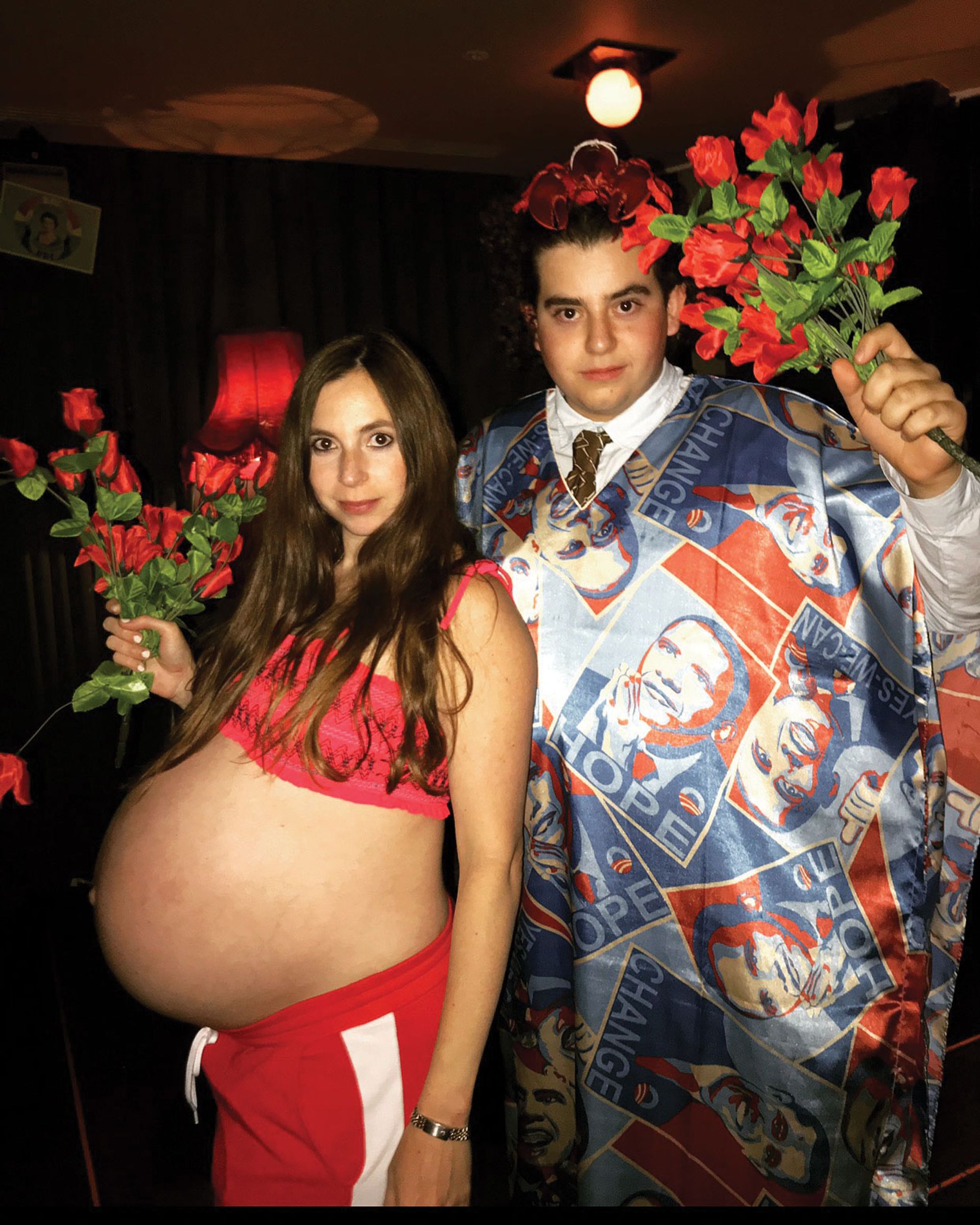

Helen Benigson Courtesy of the artist

Helen Benigson, artist

Two children, aged three and seven months

Helen Benigson’s two pregnancies have formed the subject of her PhD at the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford, recorded in video and performance pieces, some of which will be shown at London’s Roman Road gallery this month.

“It felt a bit extreme to propose it as a topic before I knew I was actually pregnant. But I always knew I wanted it to be the subject,” Benigson says. She is not represented by a gallery and says: “Doing a PhD as a female artist is quite amazing because it’s one of the only times, apart from if you teach, when you’re paid maternity leave—and you get paid to do the PhD.”

Benigson now gets calls every week from other female artists thinking about becoming pregnant, asking if they should do a PhD. “I think women are realising it’s a good way to have your babies and not completely lose touch, because there’s still a structure in place.”

After her first birth, Benigson went back to work after one term. Now, however, after the birth of her second child, she is only just returning to work after seven months. “It’s quite a strange thing for an artist to take maternity leave, because there’s this presumption that they will just make work all the time,” she says. To fit in studio time, she works late and has childcare. But that is not an easy decision for an emerging artist: “It makes you ask, ‘Can I justify paying someone else to look after my child while I make work that I’m not getting paid for?’”

Victoria Siddall Photo: Kuba Ryniewicz

Victoria Siddall, director of Frieze fairs

One daughter, aged three

Victoria Siddall had her daughter Margot just 12 weeks before Frieze New York in 2016. “My mother would bring her into the fair once a day so I could feed her,” Siddall says. “We got through it!”

Siddall became pregnant just as she was made the director of Frieze’s three fairs in the US and UK. It was, she says, difficult to land on the right moment to have a child: “When your job is interesting and your career is progressing, then it’s never going to feel like a good moment.” As she says: “Your career you can take into your own hands and control, whereas you cannot really control having a child. That said, having done it, I know it’s possible!”

Siddall theoretically took four months maternity leave, though she was “in and out of the office—doing the job I do, I couldn’t just disappear”. She stresses, however, that it was her choice.

Attending gallery private views and dinners is a (non-child-friendly) part of the job, and Siddall, who has a nanny, manages it by going home after work, doing the bedtime routine, and then going back out for dinner. “I work with a lot of younger women and it’s important to show them that it’s possible to have a serious role in the art world and have children,” she says. “So, I’m always happy to speak about it and not hide it away, as if it’s something that might be detrimental to my career. Everyone can do this—they’ll just figure out their own way.”

Caption: Annie Morris with stacked ball sculptures that she developed after her child was still-born © Leon Chew

Annie Morris, 41, artist

Two children, aged five and six

When Annie Morris and her husband, the artist Idris Khan’s first child was stillborn, her grief sparked a new series of work: Morris started making biro drawings of women, and adding collage. “Then I started collaging these egg shapes—this egg that I’d been carrying and lost,” Morris says. And it was out of this that her stacked coloured ball sculptures emerged: “I had such a bad experience with the still-birth, then struggling to get pregnant again, in a way this whole body of work would not have existed had that not happened.”

Today, the couple have two children and Morris went straight back to work after both: “Idris and I were maybe a bit naive—we had this vision of buying one of those chairs on wheels and she [their daughter] could sit in there in the studio while we were working. It didn’t quite happen like that but we had her in the studio.” Today Morris takes her children to school then works from nine to five in the studio.

“There’s no question that [being a mother] becomes three quarters of what you’re thinking about. You only have that other quarter left to think about work,” Morris says.

The couple used to share a studio with Chantal Joffe and, Morris says, “We used to talk about the fact that, when you’re pregnant, you can’t really use the same materials, like white spirits and oils and turpentine—more toxic things.” Joffe started working pastels when pregnant, and Morris says: “It would be an interesting exhibition to look at how women change their materials through those nine months.”