Despite having long since emerged from the shadow of her husband Jackson Pollock, Lee Krasner has not had a show in the UK since the Whitechapel Gallery’s in 1965. This week’s exhibition at the Barbican Art Gallery is therefore overdue. Indeed, it begs the question why the Tate—which in the past brought in exhibitions from the US devoted to other Abstract Expressionists such as Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko—is not putting on such a show. Perhaps it has shifted its agenda to more modish spheres. Then again, other important names in the Abstract Expressionism pantheon—think Sam Francis, Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt—have not received their full due from any London museum either, though the first two have been seen adequately elsewhere in Europe.

The Barbican therefore goes where others fear or disdain to tread. The show also follows appropriately in the wake of the Royal Academy of Arts’ 2016 Abstract Expressionism exhibition, the largest such survey ever mounted in Europe. There, Krasner’s magnum opus The Eye is the First Circle (1960) held its own in a gallery of major Pollocks. Will Krasner’s star shine as brightly when the Barbican displays far more of her opus?

Lee Krasner's Self-Portrait (around 1928) © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation. Courtesy of the Jewish Museum

Re-evaluating Krasner began with the revisionist art history of the 1970s that rightly regarded the traditional Abstract Expressionist canon—first established by the sexist Clement Greenberg and amplified by Irving Sandler’s 1970 book Triumph of American Painting—as more or less restricted to dead white males. Ongoing feminism fuelled this shift in perspective, mainly for the good but sometimes overstating its case for reasons of gender revanchism. For example, a survey seen at the Brooklyn Museum in 2000 left mixed feelings. In short, Krasner appeared then as an uneven artist and one who was not quite such an outsider as the curatorial thesis suggested. Nor did Krasner ever establish a signature style. Instead, she roved restlessly over the decades between late Cubism, collage, calligraphy, minuscule and epic scale.

Lee Krasner's Untitled (1946) © Jonathan Urban

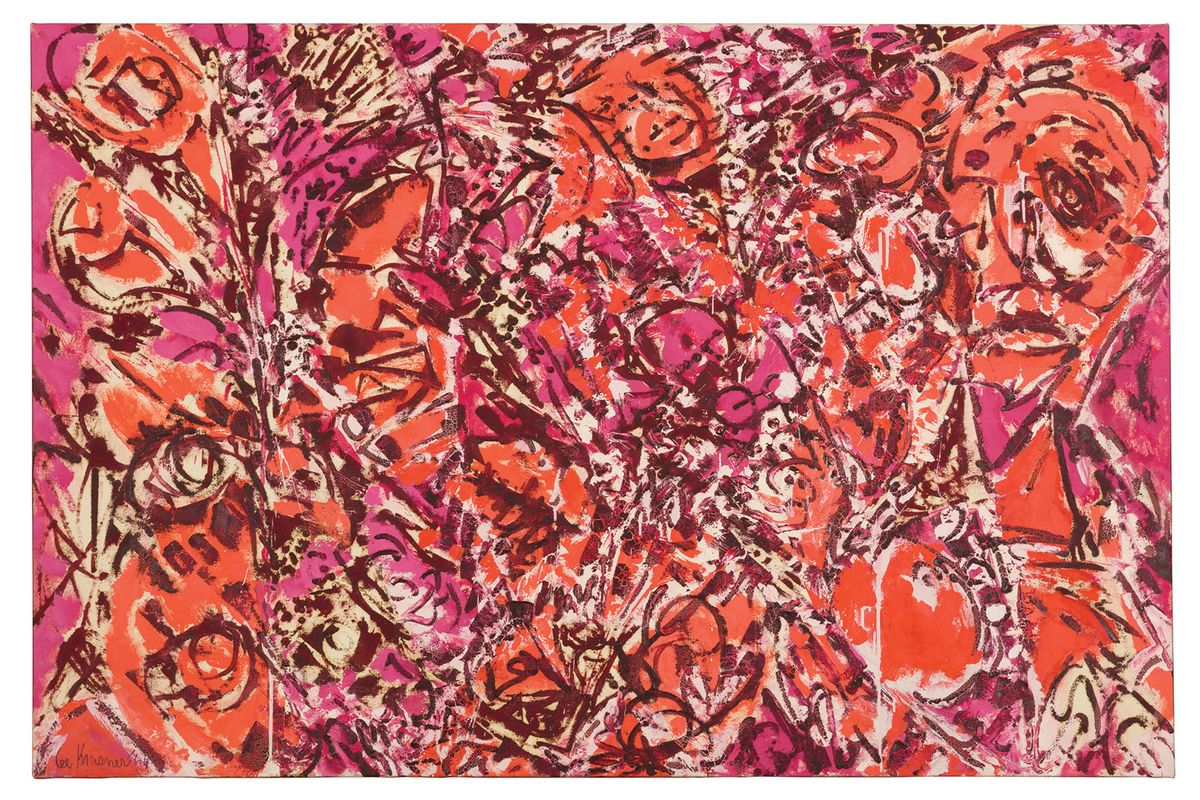

Krasner’s first truly original work was perhaps the Little Image series at the end of the 1940s. They were complex and innovative compositions, especially in the allusions to hieroglyphics and Hebrew script, yet maybe not without some debt to Mark Tobey, just as the collages of the next decade look to Henri Matisse in their lush hues and curvaceous planes. With the great Umber sequence (1959–62) Krasner finally found herself. Last year Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York gave these canvases a powerful exhibition and scholarly publication to match. Hopefully the Barbican will set them in even sharper focus.

What especially fascinates about the Barbican’s approach is the subtitle, Living Colour. It remains to be seen whether Krasner’s forte was colour or, rather, line. The accompanying catalogue should help answer this question as much as the selection itself. Of the four essays, the curator Eleanor Nairne finds a new and convincing colourful source in Vincent van Gogh for Krasner’s self-portrait from around 1928, while the critic John Yau is his usual incisive self. Above all, the show may conclusively determine whether Krasner or Joan Mitchell was the finest of the female Abstract Expressionists.

• Lee Krasner: Living Colour, Barbican Art Gallery, London, 30 May-1 September