The British artist Anish Kapoor today unveiled a new series of paintings, depicting blood streaming from wounds, or, it would seem, vaginas.

His fascination, he says, stems from blood as “ritual matter”, but also its association with “the abject, with death, with the impure”. He adds: “It’s so strange that both are a place of origin and a place of dirt, or other matter, menstrual [blood].”

Speaking at the unveiling of the works at London’s Lisson Gallery, Kapoor—who last weekend was listed in The Sunday Times Rich List 2019 at 876th, with an estimated wealth of at least £135m—acknowledged the problems he faced as a male artist addressing issues such as menstruation. “One of the things that arises is, inevitably, can a man deal with women’s questions? Is a man allowed to?”

Kapoor says that the “whole point” of artistic practice is that “reality can be borrowed, to be shared, envisioned, imagined”. He argues that it is a “kind of purity [to say] you can only do it if you are really black, or really Indian or if you are really a man. The point is to measure the work, not in terms of whether a man is allowed to do it or not, but in terms of whether it’s any good or not”.

He defended the US artist Dana Schutz, whose painting Open Casket sparked protests at the 2017 Whitney Biennial for its portrayal of the corpse of the black teenager Emmett Till, who was lynched by two white men in 1955. “What a weird idea, that a white artist makes work that is supposedly cultural heritage of black artists and she is given shit for it. How can it be?” Kapoor says.

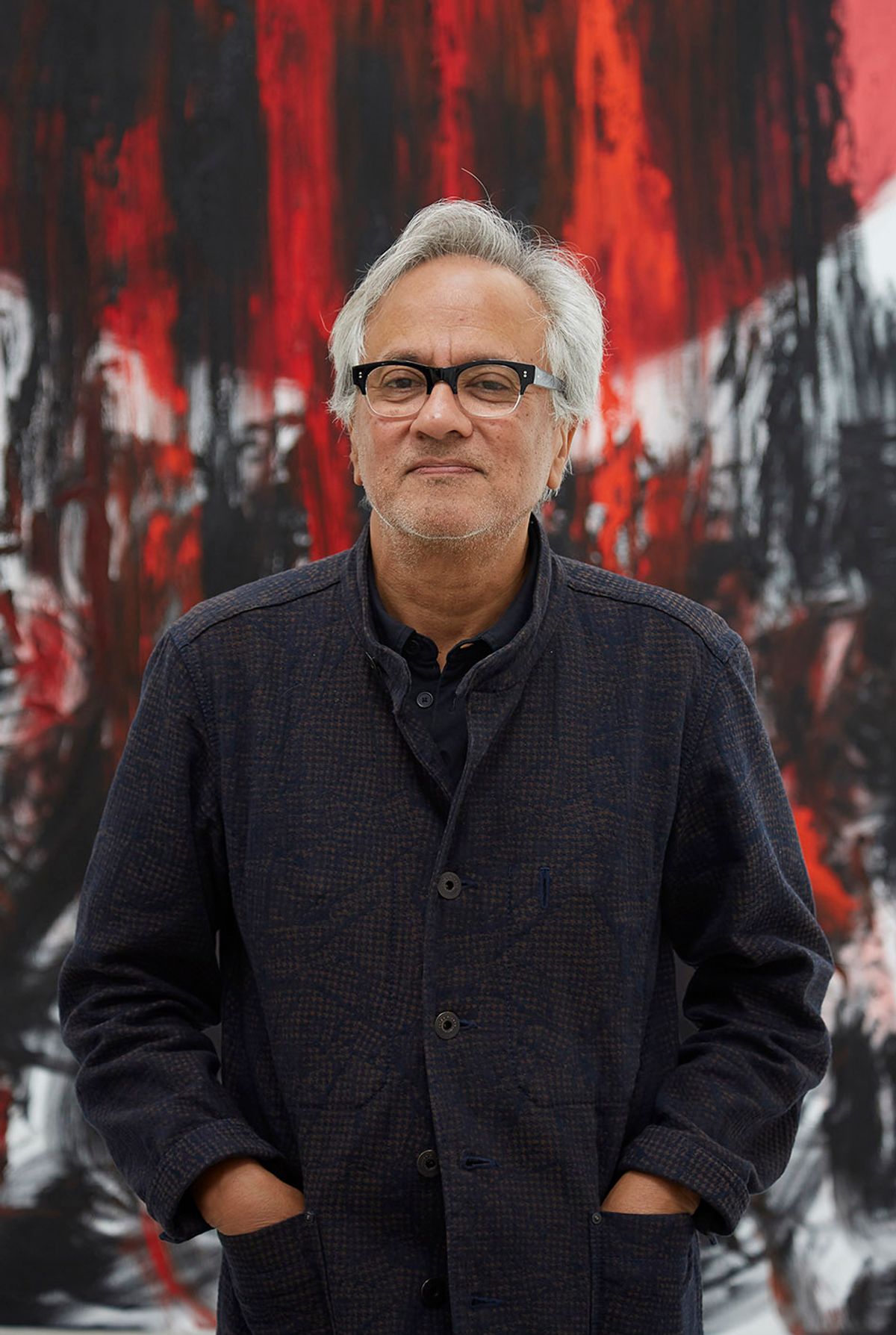

Kapoor went heavy on the red paint for his new series of works Courtesy of Lisson Gallery and the artist

It was also announced that Kapoor is to have his first major solo show in China this autumn. The sprawling retrospective will take place across two locations: the Central Academy of Fine Arts Museum and the Imperial Ancestral Temple, by the walls of the Forbidden City in Beijing.

Built during the early Ming Dynasty in 1420, the Forbidden City attracts more than 10 million visitors annually. As a place where Chinese emperors worshipped during ancient festivals and ceremonies, the Imperial Ancestral Temple is one of the most sacred sites in Imperial Beijing and has never been used for a contemporary art exhibition before.

Kapoor’s relationship with China has not always been plain sailing, however. In 2015, he criticised the country’s stance on copyright after an uncannily similar version of Cloud Gate, his bulbous monument in Chicago known as the bean, appeared in the town of Karamay in the Xinjiang region of China.

Kapoor today described the situation as complicated. “I did at first try quite robustly to fight a plagiarism case but things take so long,” he says. “It’s going, but very slowly. We’ll see, copyright in China is very complicated.”