Claude Monet cast a long shadow over 20th-century art after he died in 1926. Indeed, his impact still lives in the paintings of a contemporary such as the octogenarian Larry Poons. They continue the lyrical, evanescent spirit of his French predecessor more vigorously than ever. This is not the first exhibition to tackle Monet’s legacy. On the contrary, at least three major ones have already addressed the subject: in Madrid, Munich and Boston/London. None, though, were so focused on American abstraction. Nor did they have Les Nymphéas (Water Lilies) as their lynchpin and cornerstone—in this case, literally more or less part of the Musée de l'Orangerie’s architecture. The museum has at last played its trump card. The move feels at once impressive overall and in places problematic.

In 1952 André Masson likened Monet’s eight vast panels to “the Sistine Chapel of Impressionism”. In their sheer encompassing sweep, these panoramas still retain something of that frisson. Not quite “apocalyptic wallpaper” yet not too far removed from the sentiment either—provided one replaces “apocalypse” with “contemplation” and considers them an apotheosis of decorative impulses rather than in the derogatory terms of “wallpaper”. Far from being a backdrop, the Orangerie’s two oval spaces are immersive, the key quality that anticipated Modernist painting’s shift from the easel to diverse larger expanses beyond it.

Monet's Les Nymphéas at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris Musée de l’Orangerie, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Sophie Crépy Boegly

“Modernist”, that is, if one accepts the US critic Clement Greenberg’s narrative theory of a progressive surrender to the medium, a pictorial push towards flatness, homogeneity and blandness. Unfortunately, none of the Abstract Expressionists did. The show and catalogue seek to make a virtue of this mismatch. Thus, the curatorial thesis pivots around the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) acquisition of a large Water Lilies in 1955 and the accompanying critical debate. By then, first-generation AbEx (to abbreviate the long-winded term) peaked, while Greenberg had visited the Orangerie the previous year. The stars were aligned for some successor to AbEx or at least a shift from its stress on what Rothko had earlier called the “tragic and timeless”. Enter Abstract Impressionism, a fuzzy concept that barely gelled enough to form a “movement”.

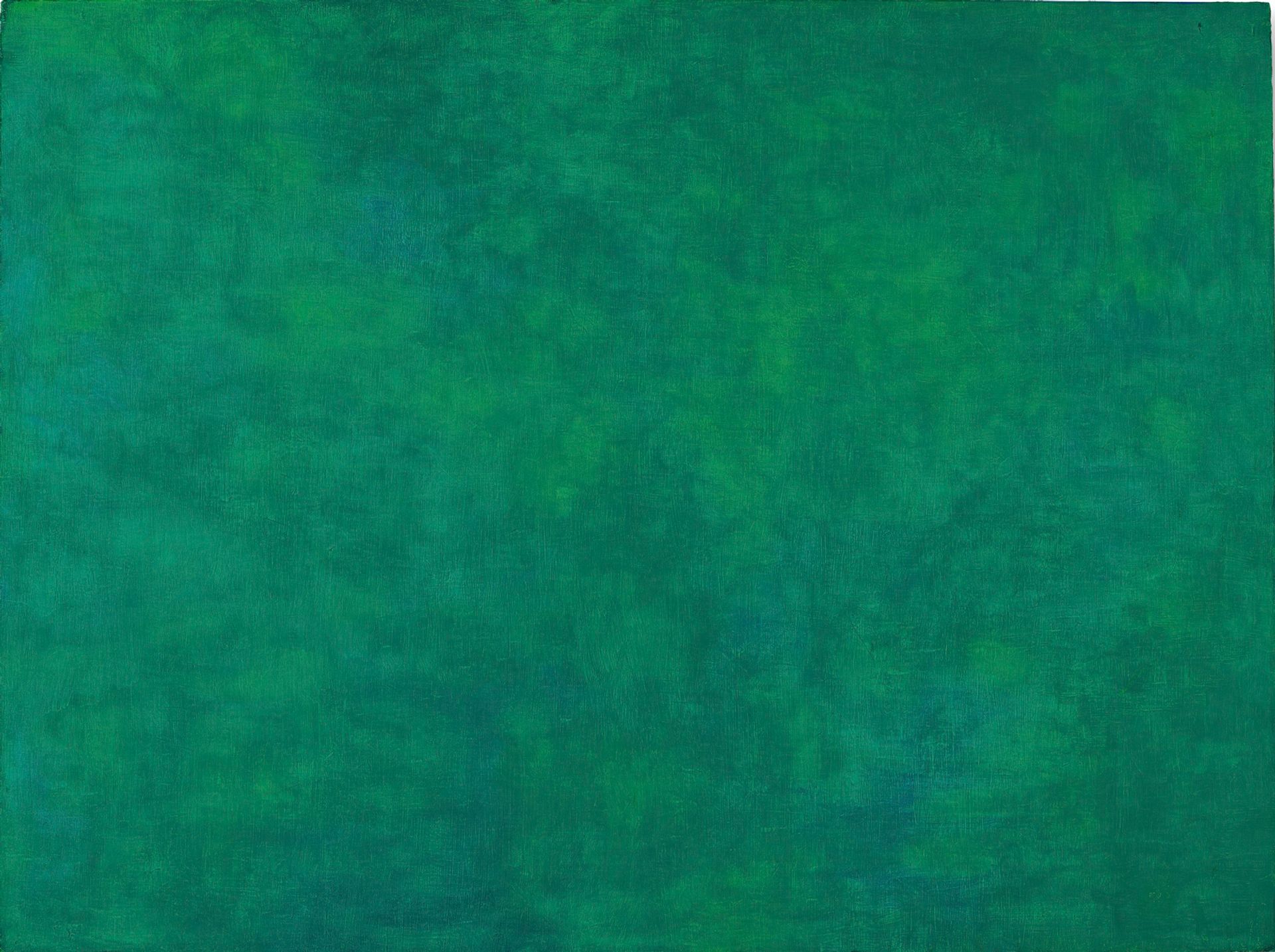

But the show opens with a lovely retrospective touch. On the ground floor near the entrance and immediately before the two big rotundas holding the Monets, stands a simple tribute to Ellsworth Kelly. A 1968 suite of Kelly’s ultra-sparse ink drawings of water lilies flank his little, though seminal, Tableau Vert (1952). It extracts the essence—chromatic vibrancy—from Monet’s “envelope”, the atmosphere that he felt enwrapped everything. This gallery also serves as a reminder that once the war was over, Americans again headed back to Paris and away from uptight McCarthyite America. The luminaries included Kelly, Sam Francis and Helen Frankenthaler alongside now almost-forgotten figures such as Beauford Delaney (black and, like Kelly, gay) and Ary Stillman (who had shown with other AbEx artists at Betty Parsons Gallery). Of course, Joan Mitchell—she eventually settled in Vétheuil—inherited de facto Monet’s mantle. Downstairs, the main display starts with a spectacular 1980 polyptych by Mitchell in which fluttering verdancy reigns.

Ellsworth Kelly's Tableau Vert (1952) The Art Institute of Chicago; Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

Then the AbEx connections go haywire. Although Barnett Newman rebuked MoMA for delaying until 1953 to acquire its first Monet, nothing connects his The Beginning (1946) to the latter. Likewise, Pollock’s The Deep (1953) is a homage to Clyfford Still, not Monet. True, Still owned a clipping of Monet with the Water Lilies. However, the polymath Westerner collected images of everything from African art to Renoir and cartoons. As for Rothko’s two multiforms, it was Bonnard’s 1948 memorial exhibition at MoMA that helped them dissolve erstwhile figurative presences into glowing fields. In turn, Greenberg’s 1955 essay “American-Type” Painting deliberately misread these fields and Pollock’s skeins as heir to Monet’s “allover” empirical sensuousness rather than visionary and sublime existential icons.

The obsession with Greenberg feels unhealthy. It at once provides a theoretical structure to the display and misrepresents the art history at stake. Nor does a catalogue in French alone help clarify the argument’s scholarship (at least to non-Francophones). Also, several artists whom Louis Finkelstein named in his 1956 article that most fully identified “Abstract Impressionism”—among them Nell Blaine, Robert Goodnough and Ray Parker – are missing. And Guston’s powerful painterly phantasmagorias of the mid-1950s look more laden with angst than hedonism.

Installation view of The Water Lilies: American Abstract Painting and the last Monet exhibition at the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris Musée de l'Orangerie

Fortunately, the installation turns a corner in every sense with Morris Louis’s two shimmering veils. These accurately reflect Greenberg’s advocacy for “Post-Painterly Abstraction” by the early 1960s. It was an art geared to air, lightness and largeness of which Monet himself would likely have approved. A magnificent aqueous-blue Frankenthaler and Francis’s aptly titled Round the World (1958-59) preside over these final spaces abetted by Jean-Paul Riopelle’s rich Untitled (1954) canvas. A Jules Olitski would have been a nice addition, as would a Larry Poons. Highly enjoyable, this exhibition is nevertheless at times a bit, well, impressionistic.

• The Water Lilies: American Abstract Painting and the last Monet, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris, until 20 August

• David Anfam is an art historian, the senior consulting curator at the Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, and co-curated the Royal Academy of Art’s major survey Abstract Expressionism in 2016