Art and football, in combination, do not seem to have a rich, fruitful history, unlike boxing and cinema or flâneuring and literature. But in recent decades, with an increasing amount of global wealth poured into both, comparisons have started to emerge—not least a shared excess of capital and skewed markets in which products are worth whatever one billionaire is willing to pay above another.

This may be a little disingenuous, however; look a little closer and there are many artists who turn to football for inspiration (there is even a new magazine, called Oof, devoted entirely to the subject). As the 2018 Fifa World Cup kicks off in Russia, a slew of exhibitions and artists are showing how the two opposing worlds clash, like the Swiss minnows up against Brazil’s fabled seleção on Sunday (17 June).

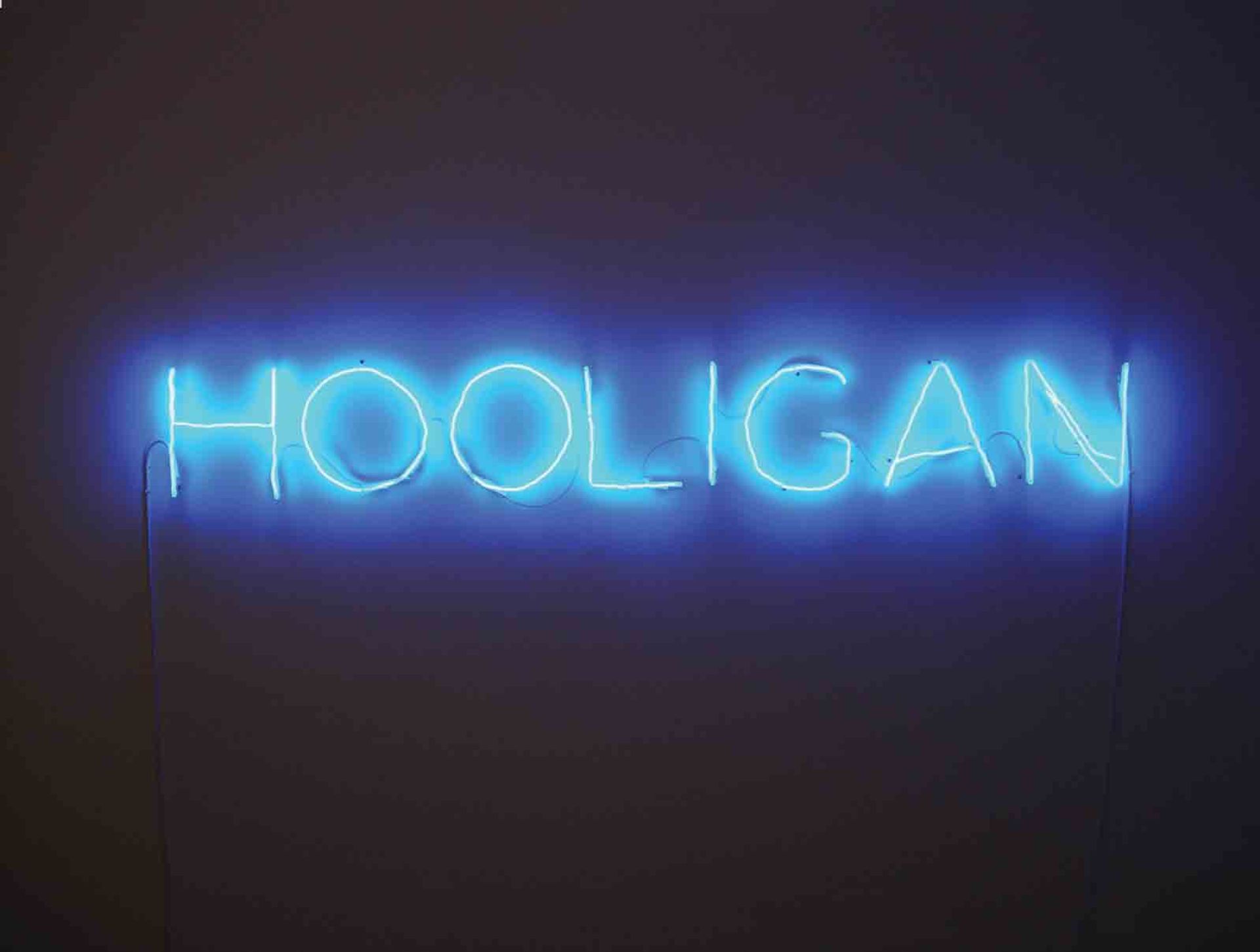

Claude Lévêque’s Hooligan (2006) is on display at Magasins Généraux, just outside Paris ADAGP Claude Lévêque; Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour; Paris/London

A good example of how the upper echelons of art and football cross over is the Russian oligarch and billionaire Roman Abramovich. Outside the art world, he is perhaps best known for buying Chelsea Football Club in 2003 and bankrolling the most successful period in the club’s history, but he is also an avid art collector. In 2008, Abramovich bought Lucian Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping (1995) for $33.6m, a record for a living artist at the time, and in the same year co-founded Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art with his then wife, Dasha Zhukova. This summer, the museum celebrates its tenth anniversary with an exhibition on football by the German photographer Juergen Teller.

“[Teller] is one of the biggest fans I know—he is obsessed with football,” says the museum’s chief curator, Kate Fowle. The show, Trembling on the Sofa (until 19 August), includes images of the photographer in a hotel room with the Brazilian legend Pelé, stalker-style snaps of the manager Pep Guardiola and a portrait of the film star Charlotte Rampling in goal. However, the main installation will be closely entwined with the success or failure of the German national team at the World Cup.

Teller has set up seven screens—the potential number of games played by Germany, should the team reach the final—which, instead of showing the team’s matches, will relay footage of the artist watching the games with family and friends, replete with the inevitable euphoria or anguish. If the team is knocked out early in the competition, the remaining screens will be scrambled, as if the tournament no longer exists. But if “they win [the World Cup], there will be a cacophony in there”, Fowle says. Teller also has a show at the Fotomuseum Winterthur, near Basel, called Enjoy Your Life! (until 7 October).

Museums across Russia, the host nation, are hoping to attract some of the football fans going through the turnstiles at 12 stadiums in 11 cities. Moscow’s Museum of Architecture has organised an exhibition looking at a century of sporting stadium design in Russia; The Architecture of the Stadiums (until 26 August) includes the history of the Luzhniki Stadium, where the first match of this year’s tournament took place on Thursday. It also features designs for a U-shaped stadium with two playing fields, and for a stadium with a motorcycle track running around the perimeter. At the nearby Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, a small exhibition (until 15 July) of nine football-themed works by the Russian avant-garde artists Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova will include the latter’s striking geometric kit designs.

Kit designed by Varvara Stepanova in 1923 Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts

The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg is offering the services of one of the many cats that live in the institution’s basement. During the 2017 Fifa Confederations Cup, Achilles successfully predicted Germany’s victory over Chile in the final by choosing a bowl of food placed near the country’s flag. He is due to get back to work in divining the World Cup scores.

In Germany, the Center for Art and Urbanistics (ZK/U) is hosting a series of events tackling the “image of Russia”. The project, titled Fussballaballa (until 15 July) and running in parallel with the Berlin Biennale, which opened last weekend, is organised by the artist collective KUNSTrePUBLIK. The first edition, which took place during the 2014 World Cup, focused on the host country, Brazil, and urban change; for the Euro 2016 tournament in France, the spotlight was on immigration in Europe. The aim this year is “to look beyond the headlines made by Putin, the oligarchs and new Cold War narratives [to unveil] a socially diverse country with contradictions, surprises and an ethnically diverse civil society”, the organisers say.

“Ropac! Ropac! À L’attaque”, is written across a red football scarf held up by the young French artist Aurore Le Duc for her Supporters de galeries series (2015-present), which includes various items of football merchandise dedicated to art galleries. Le Duc is one of 11 young artists (out of 38 in the show) commissioned especially for the exhibition For the Love of the Game 1998-2018 (until 5 August) at Magasins Généraux in the Parisian banlieues, where many of France’s greatest footballers grew up. The curators, Anna Labouze and Keimis Henni, say that their aim is to explore football “in a poetic and humorous way, and as a social phenomenon”. It is the inaugural show for the organisation, which was founded by the advertising agency BETC. The dealer Thaddaeus Ropac opened a gallery space nearby in 2012.

Even Art Basel’s sister city Miami is getting in on the act, although the US team failed to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1986. The director of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, Franklin Sirmans, who “grew up playing” football and is an “avid fan”, says Miami is “unlike any other US city” in its love for the game. Among the 50 works in The World’s Game: Fútbol and Contemporary Art (until 2 September), he highlights Stephen Dean’s video Volta (2002-03), which shows a crowd seemingly moving as one, and Lyndon Barrois Jr’s depictions of the “women heroes” of the US game—who, unlike their male peers, are the most successful team in international football.