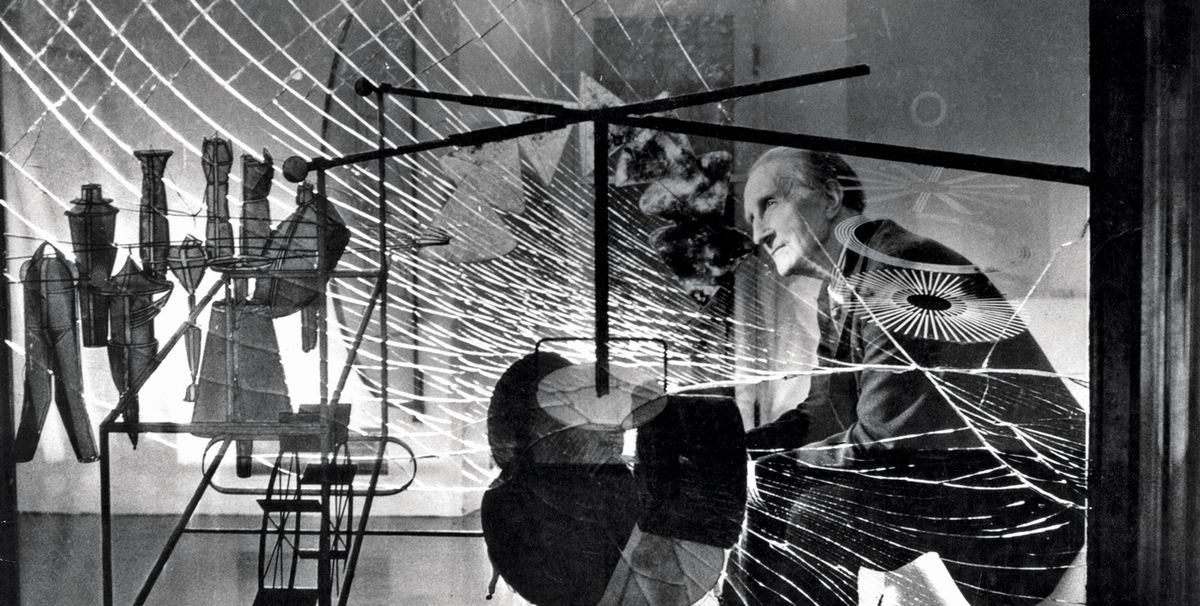

At the end of his interview with Joan Bakewell on the BBC’s Late Night Line-Up on 5 June 1968, Marcel Duchamp tells Bakewell, “Well, I’m delighted.” Leaning forward, he flashes her an appreciative gaze before sitting back in his chair, taking a long puff on the cigar he has chugged on throughout the interview and surveying the scene around him. These are the final moments of Duchamp’s first and last live television interview. In the early hours of 2 October of that year, after a long dinner at his home in Neuilly-sur-Seine with his friends the artist Man Ray and the critic Robert Lebel, Duchamp died, aged 81.

Fifty years on, the interview remains a compelling watch. Duchamp’s significance was not what it is today but his reputation had risen again, after years in which it was thought he had given up art for chess. Artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage had befriended him and seen him as a mentor. They prompted a revival of interest in the 1950s that was bolstered in the 1960s by Pop artists in Britain and the US and the first stirrings of conceptualism. It was only then that Duchamp had his first retrospective, at the Pasadena Art Museum in California in 1963. That was followed by one at the Tate Gallery in London in 1966.

Bakewell remembers that Duchamp was in London because he had an exhibition at the now-defunct Alecto gallery. “We knew he was very important and because we were a slightly anarchic programme, we liked people who were pushing the boat out,” Bakewell says. The interview was filmed at BBC Television Centre in west London and some of the replicas of Duchamp’s readymades, made after the Second World War and now in museums around the world, were brought to the studio for the recording. When Bakewell went to collect Duchamp in reception, she remembers that Bicycle Wheel, the first of the readymades, was standing apart from the artist. “He said he had had a wonderful time looking at people’s expressions as they saw this strange thing,” she recalls. “He had a kind of whimsical pleasure in the fact that people were baffled.”

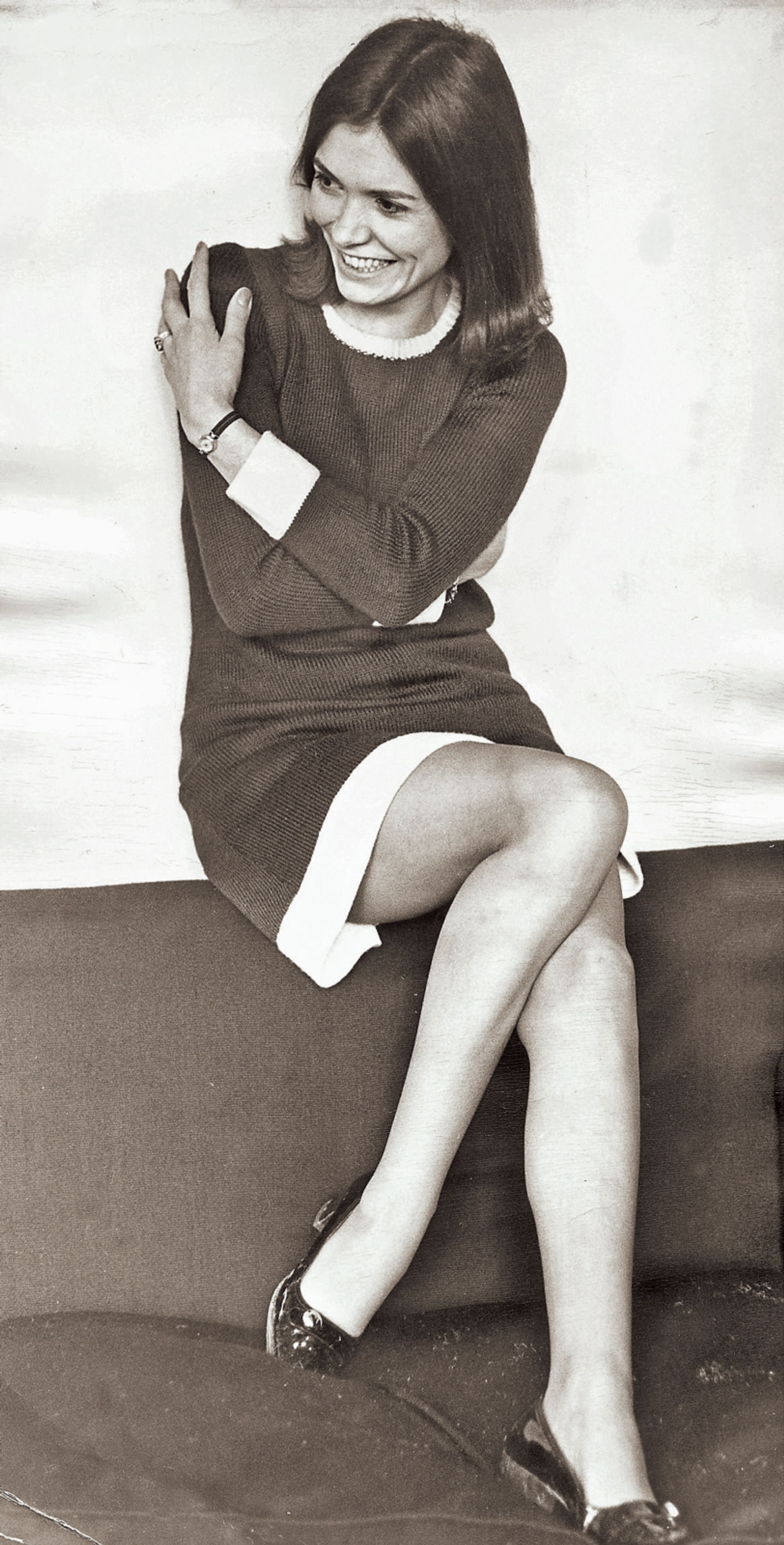

Joan Bakewell recalls that Duchamp was “quite flirty; he was very French” ANL/REX/Shutterstock

Duchamp was “almost placid”, Bakewell says. “He was very good company. He was clearly incredibly intelligent. He was full of smiles. He was quite flirty; he was very French, he had the charm of a Frenchman. He wasn’t in a hurry, he didn’t try to sell you an idea, he wasn’t pitching his outlook or anything; he was just there to share things with you, and I found that very welcoming.”

Duchamp was comfortable answering questions that other artists may baulk at, including those about his market. But Bakewell was clear that Line-Up was not a programme for combative or confrontational approaches. “If I had been a news reporter I would have said: ‘Aren’t you making a mockery of the public and how can you expect such payments for this kind of thing? It’s a spoof!’” Instead, she saw her role as an arts interviewer as being “to collaborate” with her subject.

After the half-hour conversation about his work, Duchamp confirmed his ambivalence about his position as an artist. “What he really wanted to talk about was chess,” Bakewell says, amusedly. “He said to me afterwards, because we went for a drink, ‘I’m really passionate about chess, do you know about it?’ And I said: ‘No, I’m a very poor player.’ And that disappointed him. He would have enjoyed it if I’d been a good player; we would have arranged to have a game.”

Excerpts from Joan Bakewell’s interview with Marcel Duchamp, BBC’s Late Night Line-Up, June 1968

Joan Bakewell: You attacked what you called “retinal” painting. Can you define it?

Marcel Duchamp: Yes, of course. Everything since Courbet has been retinal. That is, you look at a painting for what you see, what comes on your retina. You’d add nothing intellectual about it… A psychoanalytical analysis of painting was absolutely anathema then. You should [only] look and register what your eyes would see. That’s why I call them retinal: since Courbet, all the Impressionists were retinal, all the Fauvists were retinal, the Cubists were retinal. The Surrealists did change a bit of that, and Dada also, by saying: “Why should we be only interested in the visual side of the painting? There may be something else.”

Perhaps the most famous work of yours is the work The [Large] Glass, on which you spent eight years, and some years prior to that thinking about it. This was bringing an intellectual approach into a work of art which no one had seen for many years. There is in fact a published text which was published some time after the Glass was not finished but was abandoned. Do you wish the [Large] Glass to be appreciated with the text, to inform it?

Yes, that’s where the difficulty comes in, because you cannot ask a [member of the] public to look at something with a book in his hand and follow the diagrammatic explanation of what he can see on the glass. So it’s a little difficult for the public to come in, to understand it, to accept it. But I don’t mind that, or I don’t care, because I did it with great pleasure; it took me eight years to do part of it at least, and the writing and so forth. And it is for me an expression, really, that I had not taken from anywhere else, from anybody or any movement or anything, and that’s why I like it very much. But don’t forget that it never had any success until lately.

[The Large Glass] was taking eight years and, at the same time, you designated certain objects as readymades. What sort of effort went into the choice of the object you designated?

In that case, my idea was to find—or not even to find, but to decide, to choose—an object that wouldn’t attract me either by its beauty or by its ugliness. To find a point of indifference in my looking at it. Of course, you might say I could find any number of those. But, at the same time, not so much, because it’s difficult after a while when you look at something—it becomes very interesting, you can even like it. And the minute I liked it, I would discard it. So the choice came [down to] only a few objects, quite disparate and different from one another. Enough so that, today, looking at the 13 readymades I made in the course of 30 years, maybe, I’m satisfied by the fact that they don’t look like one another. In other words, there is difference, completely—a strangeness from one to the other that shows that there is no style there.

I don't care about the word 'art', because it has been discredited

What you were also attempting to do, as I understand it, was to devalue art as an object, simply by saying: “If I say it is a work of art, that makes it a work of art”.

Yes, but the [term] “work of art” is not so important to me. I don’t care about the word “art”, because it has been so discredited.

But you contributed to the discrediting, didn’t you, quite deliberately?

Deliberately, yes. I really wanted to get rid of it, in a way many people today have with religion. There is an adoration of art today that I find unnecessary, and I think, I don’t know… This is a difficult position because I have been in [art] all the time, and still want to get rid of it.

The anti-art movement of Dada was proved to be in the interest of art, because it regenerated and revived and freshened people’s attitude to it. Do you anticipate that your own contribution when the final reckoning comes will have in fact contributed to something called art?

I did in spite of myself, if you wish to say… But at the same time, if I had [abandoned art], I would completely have been not even noticed… There are probably 100 people like that who have given up art and condemned it and proved to themselves that [art] is no more necessary than religion and so forth. And who cares for them? Nobody.

But nonetheless a lot of people care about art, because it’s worth money. And in designating certain objects and signing them with your name, you have created a highly commercial object. In 1964, a new product [edition] was actually manufactured so that you could sign it, so that you could produce an edition of readymades with a value of something like £2,000.

Well, alright, but this is not high enough. I’ll tell you why: because when you compare this to a painting by anybody you might name, you’ll ask the difference of price between the painting, at least by a well-known painter. Even so, I am in the lower bracket, that’s what I mean, and I excuse it for that reason, by being in the lower bracket instead of a high bracket—so £20,000, £20m, if you wish to say, when you come to Cézanne or even Picasso. See, [the price of the readymades] doesn’t compare with a painting.

No, indeed it doesn’t, but if you were following through your determination to devalue art, what would happen if in fact these manufactured readymades were mass-produced and we could all buy one for two shillings?

No, no, no, you have to sign them. They are signed and numbered, in an edition of eight each, like any sculpture. So it is still in the realm of art, in the form of technique, you just make eight and you sign them and number them, so that’s the end of it. You should never have one more, even if you could find them in the shops.

So that, in fact, as far as that side of your work has gone, the actual production and signing and selling of your work, you’ve stayed very much within the accepted standards of the art world.

Yes, in fact I had to, because otherwise where would I be? I’d be in an insane asylum, probably.

Duchamp’s Bottle Rack (1914/1959), a readymade that once belonged to Robert Rauschenberg and was recently acquired by the Art Institute of Chicago Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris, and DACS, London, 2018; courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago

In terms of the activities of the Dada group other than painting, the sort of happenings that they devised are in fact happening again: they are called “happenings” today. Do you ever see or engage in these events or feel any fellow feelings about them?

I love the happenings, I know Allan Kaprow… and it’s always amusing. And the point that they have brought out so well, an interesting one, is that they play for you a play of boredom… It’s very interesting to have used boredom as an aim to attract the public. In other words, the public comes to a happening not to be amused but to be bored. And that’s quite a contribution to new ideas, isn’t it?

When you set out to challenge all the established values, your means were shock. You shocked the Cubists, you shocked the public, you shocked the buying public. Do you think the public can be shocked anymore by anything?

No, it’s finished, that’s over. You cannot shock the public, at least with the same means. To shock the public, we would have to do I don’t know what. Even that thing with the happenings, boring the public, doesn’t prevent them from coming—the public comes and sees anything that Kaprow does, or Oldenburg and all these people. And I have been there, and I go there every time. You accept boredom as an aim, an intention.

Do you regret the loss of shock or do you think it’s the artists’ fault that the public simply always expect to be shocked?

No, but the shock would be of a different character… probably the shock will come from something entirely different—as I say, non-art, “anart”, no art at all, and yet something would be produced. Because after all, the word art etymologically means to do, not even to make, but to do—and the minute you do something you are an artist. In other words, you don’t sell your work, but you do the action. Art means action, means activity of any kind.

So everyone…?

Everyone. But we in our society have decided to make a group we call artists and a group we call doctors, which is purely artificial.

In the 1920s, you proclaimed art is dead. It isn’t, is it?

Yes, well, that is what I meant by that. I meant that it’s dead by the fact that instead of being singularised, in a little box—so many artists in so many square feet—it would be universal, it would be a human factor in anyone’s life; to be an artist, but not noticed as an artist.

• To watch the full interview, visit the BBC Arts website