The Americans sell arms to Saudi Arabia and the British sell arms to Saudi Arabia, but only the French sell arms and culture to Saudi Arabia. How do they manage it in a part of the world that has traditionally been part of the Anglo-American sphere of influence and where almost nobody speaks French? How did the French steal a march on us?

Quite apart from the sway and prestige this gives them, there is a great deal of money in play. The vast proposed museum and archaeological park at Al-Ula in the north-west of the country is a project estimated at $50bn to $100bn, of which large sums will go to France for its advisory role. In addition, the Saudis will pay for professorial chairs in Islamic culture at French universities, and for the French to train Saudi Arabia’s nascent tourist industry. French firms will be well placed to build its infrastructure, possibly to include a large seaside resort on the Red Sea.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud of Saudi Arabia is best friends with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of Abu Dhabi and will be well aware of the success that Louvre Abu Dhabi is enjoying. Rivalry between princes is a strong stimulus, so the proposed Saudi museum is to be three times the size of Louvre Abu Dhabi.

But the French connection can be traced back to 2006, when President Jacques Chirac visited Riyadh to open an exhibition from the Louvre of Islamic art and suggested to the late King Abdullah that the Saudis send an exhibition of archaeology to Paris in return. Can you imagine Theresa May or Donald Trump, or even Tony Blair or Barack Obama, doing this? But in France, culture has always been part of the ‘gloire’ of the state, and in this respect, the president is the descendant of Louis XIV.

France has had notable ministers of culture, such as André Malraux and Jack Lang, but it does not matter even when they are nonentities, because the president of the republic will lead the way, supported by the ministry of foreign affairs and the elite of the civil service. By contrast, the arm’s-length principle in the UK, which divorces culture from the centre of power to protect it from being politicised, means that government and the Foreign Office do not intervene in this way. It is up to the directors of museums, if they want to, and the British Council to play an international role—but they cannot speak as equals to heads of state.

The Saudi Archaeological Masterpieces Through the Ages exhibition (later called Roads of Arabia) duly came to the Louvre in 2010 and then toured Europe, the US and the Far East, amazing a public that thought Saudi Arabia was literally the Empty Quarter, nothing but sand.

Influential princes took note. Sultan bin Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud became the president of the Saudi Commission for Tourism and National Heritage and pressed for the archaeological history of the kingdom to be better known. But he had to tread carefully even as he was announcing plans for museums all over the country, because influential Saudi clerics considered the pre-Islamic past idolatrous. It was they he was really addressing when, at the University of Oxford’s Green Arabia Conference in 2014, he quoted the Prophet and said: “Islam acknowledged the great civilisations of Arabia and respected the great religions that preceded it, while consolidating existing noble Arab values.”

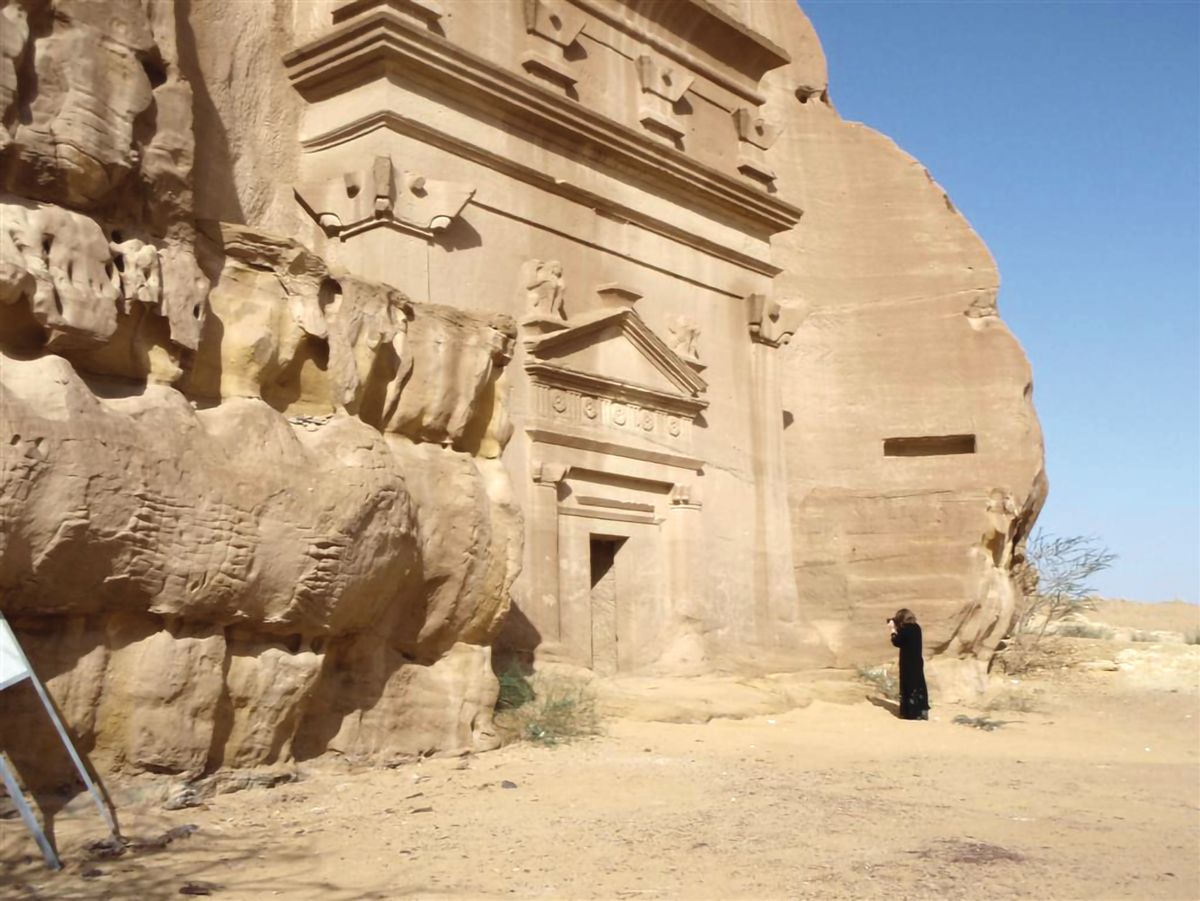

By this time, the French archaeologists were well dug in at the country’s most spectacular site, Mada’in Salih, and in 2017, the first National Antiquities Forum took place in Riyadh as Roads of Arabia finally came to the religiously conservative capital, a sign of how far the kingdom has come towards freeing itself from the tyranny of the fundamentalists.

The ground was therefore well prepared for the explosive energy of the Crown Prince to turn all of this into a ‘grand projet’ with the aid of the country that makes ‘grands projets’ a matter of national pride and knows how to sell them.