Garry Winogrand (1928-84) started as a commercial photographer and found a mission observing life on the streets, leaving many thousands of film rolls undeveloped, unprocessed and unseen before his death. He was a compulsive and poetic shooter, and he chose his subjects by following his gut, first in his native New York and then around the US. His inspirations were Walker Evans and Robert Frank, but his pictures from the 1960s through the early 1980s make for a dramatic marathon where the sheer volume of images transcends those influences.

A documentary on the artist, Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, directed by Sasha Waters Freyer, premiered at the South By Southwest (SXSW) film festival in Austin, Texas this month and will screen at the San Francisco International Film Festival (14-15 April), before it is released widely in theatres this summer and broadcast on US television as part of PBS’s American Masters series next year. The film celebrates Winogrand’s style—or anti-style—defined by encounters that often appear like collisions in public spaces. But the celebration ends with a dilemma: what do we make of the many pictures that the photographer left behind?

Garry Winogrand, New York, 1968 [laughing woman with ice cream] The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Photo: Garry Winogrand, Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona

If there is a surprise in this journey through the career of a much-exhibited photographer, it is the artist’s voice. The film includes audio recordings, like a cache of recently found interviews with the fellow photographer Jay Maisel, where Winogrand’s plain-spoken views, along with his thick Bronx accent, heighten the impact of his words into a battering ram, making heartfelt sentiments seem like arguments.

“What is a photograph?” he asks in 1974 in Austin, where he had moved from New York. “It’s the illusion of a literal description of how a camera saw a piece of time and space.” He also asks: “What does a camera do? What does photography do better than anything else but describe? To use it for anything else is rather foolish.”

“When people keep talking about photographs and depth—all a photograph ever does is describe light on surface. That’s all there is, light on surface. And that’s all we ever know about anybody, what we see.”Gary Winogrand

That same blustery photographer took pictures layered with ambiguity. Winogrand photographed interracial couples and people waiting at airports. “We see the baggage that these people are carrying. The psycho-gestural ballet that’s going on there is just extraordinary,” says Geoff Dyer, whose new study, The Street Philosophy of Garry Winogrand has also just been published by the University of Texas Press.

In his later work in Los Angeles, the longing that Winogrand witnessed in crowds and at bus stops feels like bleakness in the California sun. Friends quote him saying that taking those pictures were “the closest I can get to not existing”.

Since Winogrand avoided discussing or even acknowledging deeper meanings in his work, and since he died young, critics interviewed in the film, like Dyer, are left to debate his later pictures. The late John Szarkowski, MoMA’s former head of photography and Winogrand’s champion among curators, saw a decline in quality; others saw that chill rooted in the Reagan Era. The documentary includes plenty of pictures, so viewers can decide for themselves. Like Winogrand, the film leaves its share of loose ends and enough gaps in the narrative to send some in the audience off to Wikipedia. It is also sure to bring you back to his pictures.

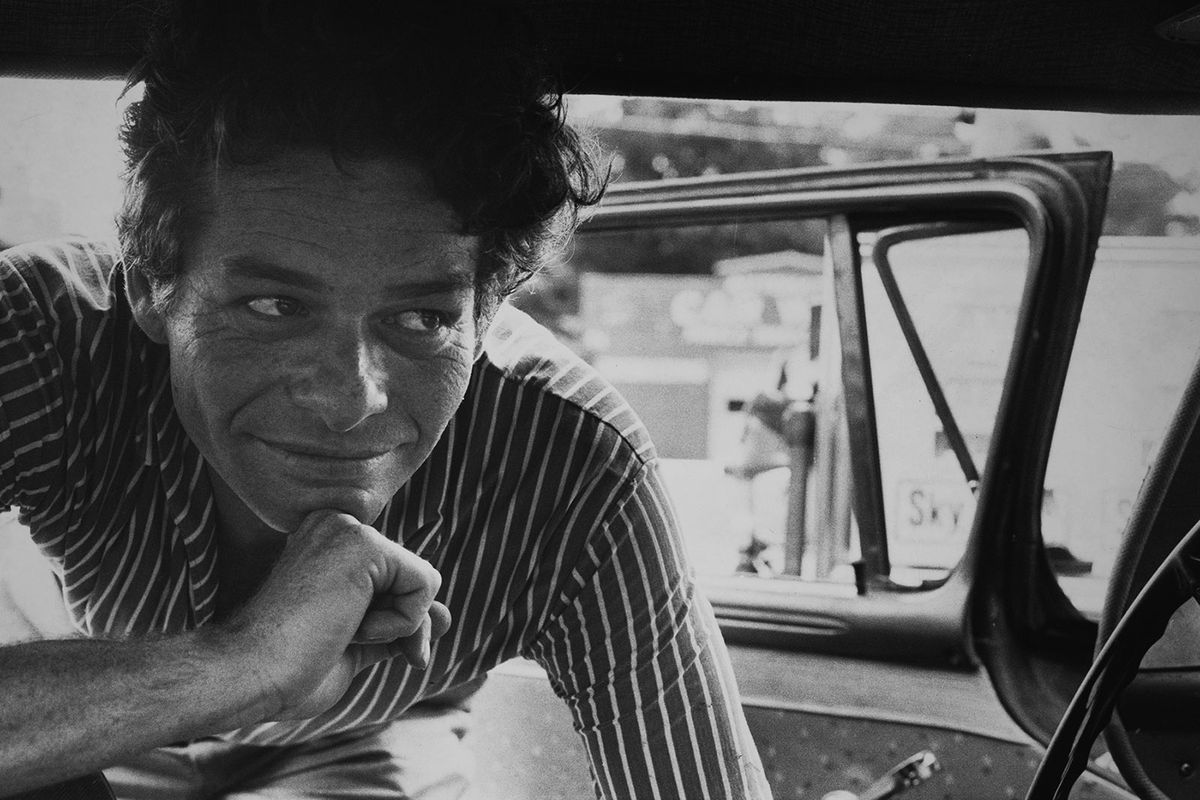

Garry Winogrand, Park Avenue, New York, 1959 [monkey in car, vertical] The Estate of Garry Winogrand, courtesy of Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Photo courtesy Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona