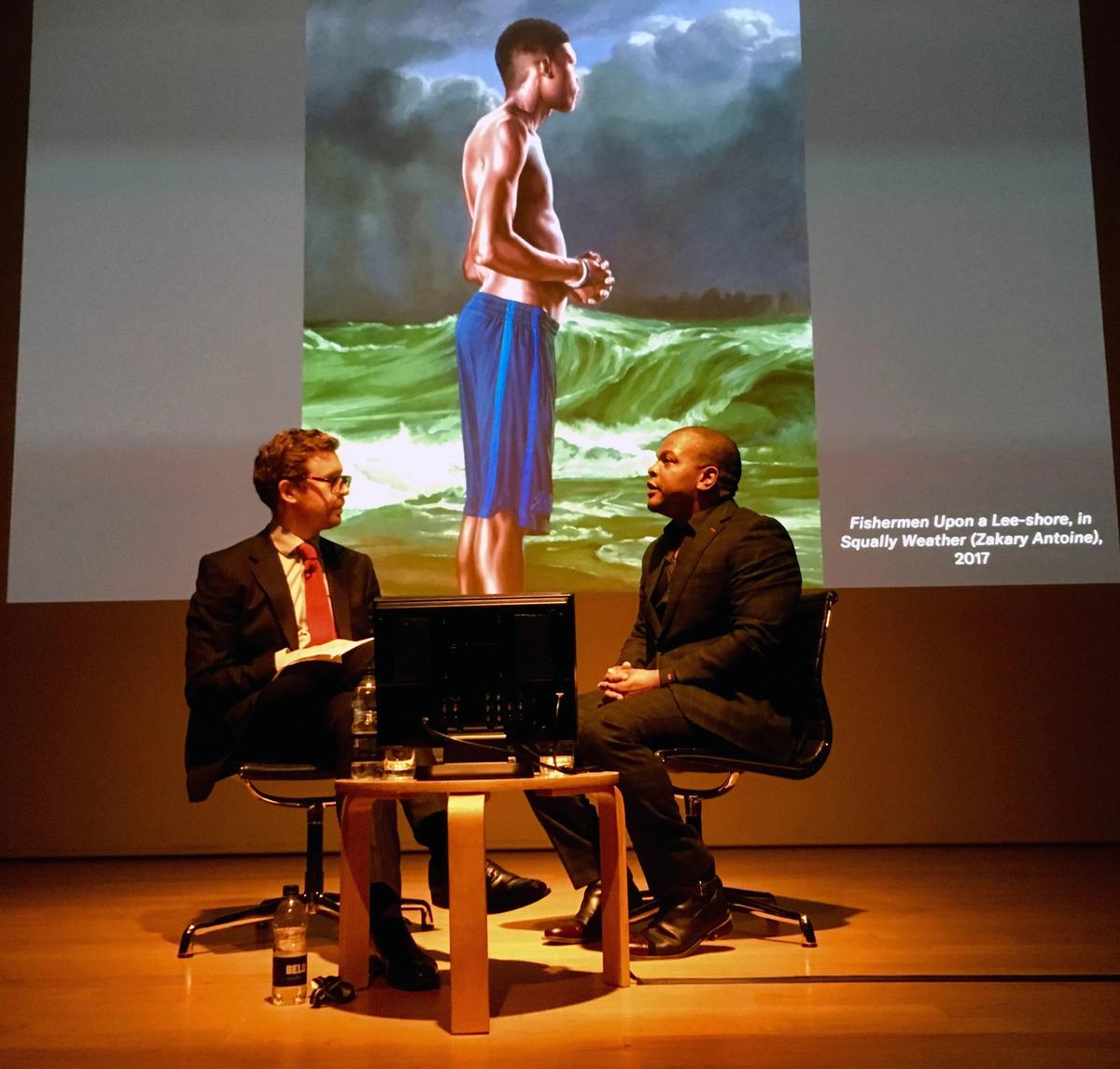

The discovery that they had been born just a day apart got yesterday’s in-conversation between the near-twins Kehinde Wiley and the National Portrait Gallery’s director Nicholas Cullinan off to a flying start. What then followed was an illuminating and animated exchange with Wiley ranging across art history as well as the current political situation both in the UK and the US: “it’s as if we all had decided to commit suicide in the face of complexity.” He is also discussed what he describes as “the radical contingency” of his working methods, which often involve inviting young black men and women spontaneously spotted on city streets to be portrayed in an art historical pose of their choice.

The New York and Beijing-based artist Wiley also talked about his stunning new series of maritime paintings, unveiled yesterday (23 November) at Stephen Friedman Gallery. These nine images of men battling stormy seas and standing contemplatively at the shoreline reboot the works of Turner, Winslow Homer, and Hieronymus Bosch to tap into the vexed history of “black bodies and bodies of water”. The show also includes Wiley’s first three-channel film, Narrenschiff (Ship of Fools) in which he grapples with the hefty themes of migration, madness and colonisation by pairing dramatic images of figures submerged in water with readings from Michel Foucault and Frantz Fanon. “I think I took on a lot for this show,” he admitted.

Although a confidentiality agreement prevents Wiley from discussing his recent commission to paint Barack Obama, he was happy to talk about his 2008 portrait of Michael Jackson, which was the last commissioned image of the star. The painting, which presents an armour-clad Jackson on a rearing steed in the manner of Rubens’ 17th-century portrait of Philip II, will form the grand finale of the show Michael Jackson: On the Wall when it opens at the National Portrait Gallery in June 2018.

Wiley paid particular tribute to Jackson’s “own deep personal understanding of painting” and revealed that the musician—who apparently owned a library of more than 10,000 art books—had engaged him in lengthy conversations about the “different brush strokes in early and late [paintings by] Rubens and the viscosity of paint—we talked about my studio practice on a granular level”. To Cullinan’s delicate enquiry as to which period in Jackson’s evolving physiognomy he had chosen to portray, Wiley diplomatically replied that such commissioned portraits create “an idealised version of who we are in the world—it's a high wire act, dealing with someone who was very loved”. However, he also confessed to a little artistic licence, cheekily adding, “skintone-wise, I gave him a little cocoa!”