At the entrance ramp that takes you into the exhibition Art and China After 1989: Theatre of the World at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, there is a modest pile of paper pulp in a wooden crate by the artist Huang Yong Ping entitled The History of Chinese Painting and A Concise History of Modern Painting Washed in a Washing Machine for Two Minutes.

The work, created in 1987 and reconstructed in 1993, gives a predictable Conceptualist take on all received wisdom—that it’s worthless.

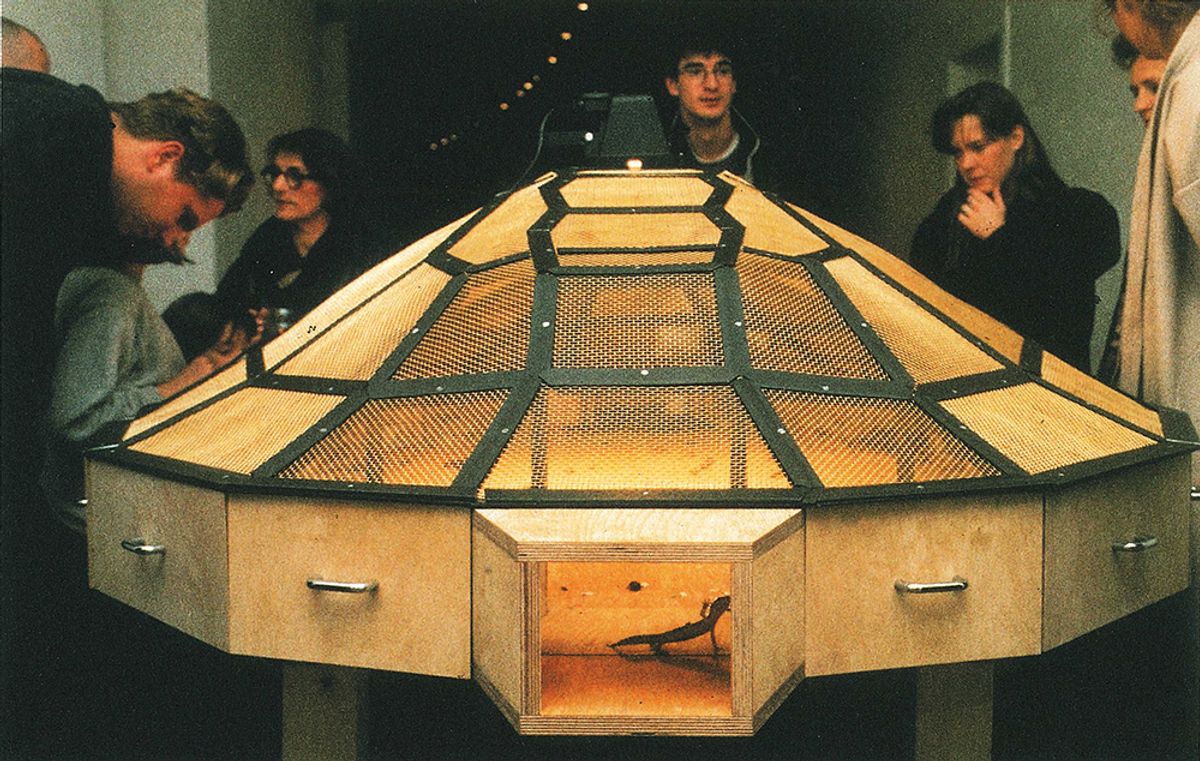

The exhibition shows around 150 works by more than 70 artists. Near the pulped book is the now-notorious Theatre of the World (1993), a sculpture also by Huang Yong Ping, who lives in France. It is a wood and metal enclosure designed to hold insects and the lizards that feed on them, with the provision that the bugs be replaced regularly as others are eaten. After a public outcry, the structure is now on view, but empty, without predator or prey.

The work, as originally intended, suggests a major theme of the show: that globalisation in China has introduced some measure of violence into the politics and culture.

Another term for the struggle for existence is dog-eat-dog—but even this one has been pulled from the show. A video clip of Sun Yuan and Peng Yu's work Dogs That Cannot Touch Each Other (2003), in which pit bulls on facing treadmills race towards each other but are held back by constrains, has also been pulled.

Farther up the ramp, the painting Burning a Rat (1995) by Liu Xiaodong offers a chilling scene, depicting two bored youths by a river bank with time to kill, literally. The silver lining to this gloomy image is that painting isn’t dead.

Visitors eager for variations on those grim insights can still get a rich, eclectic mix of art in the rest of the show, which ranges roughly from the fall of Communism in Europe to the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

The atrium of the Guggenheim spiral helps set the tone. Suspended there is Chen Zhen’s Precipitous Parturition (1999), a serpentine dragon made of bicycle tires, which is giving birth to little black cars. At its mouth are other bicycle parts, as if the dragon, China’s proud mythic beast, is overproducing machines that it risks choking on.

Farther along are more of Chen Zhen’s meditations, like Fu Dao/Fu Dao, Upside-Down Buddha/ Arrival at Good Fortune (1997), where the artist embedded a television set and other consumer objects into a canopy landscape of leaves and branches, from which inverted statuettes of Buddhas dangle.

In her catalogue essay, the curator Alexandra Munroe bemoans the art world’s focus on Chinese art as an exotic sellable novelty. “This exclusive framing… has defined a field and created a market for Chinese contemporary art over a short span," she writes. "But it has often left this art still branded as other, still orphaned in its own geopolitical and cultural era.” Her goal is to broaden the narrative.

Yet her argument runs against almost everything on view. There will be lots of talk about what this exhibition is—and even whether it is a show of Chinese art at all, since so many of the artists live abroad. Yet even as some works echo Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Beuys, almost everything points to China or views it head-on. The closer you look at the roots, the deeper they seem to go.

Part of what you see are growing pains. In the painting Mao Zedong: Red Grid No. 2 (1988) by Wang Guangyi, a portrait of Mao is overlaid with a rectilinear grid, as if the old Communist ways are now locked up. The painting also salutes the forbidden abstraction that was seductive to many artists in Mao's time. It is equally a self-directed critique—a satirical jab at the thought that artists could overcome Maoism by painting it over, like Duchamp’s moustache on the Mona Lisa.

Nearby is a meditation on information as power. Zhang Peili’s video Water: Standard Version from the "Cihai" Dictionary (1991) reminds us that fake news was the norm back then, as a deadpan news anchor ignores the Tiananmen Massacre.

For all the show’s focus on conceptualism, we see that tumultuous changes weighed heavily on artists after 1989. Rem Koolhaas, foreseeing and observing changes in the landscape, produced volumes of research on the upheaval in the Pearl River region of the south. Much of it is on view. And the output and persecution of Ai Weiwei is impossible to see absent of current events, small and large.

Ai Weiwei’s self-expanding productivity makes the show’s 2008 cut-off seem arbitrary. So does the riddle of why artists who defied the Chinese Communist party—and survived—were stymied by the protests of animal lovers in New York.

Upon hearing that his sculpture has been emptied of reptiles and insects, Huang Yong Ping recorded his thoughts on an in-flight Air France airsickness bag. “Is this not a 'miniature landscape' of a civilized nation?... An empty cage is not, by itself, reality. Reality is chaos inside calmness, violence under peace, and vice versa.”

“The curtain has fallen on the Theater of the World even before it has risen,” he noted on the bag, which is now on exhibit (and translated) in a display case.

How’s that for a conceptual twist on a message in a bottle? Even though parts of the show have been defanged, there is still plenty to chew on.

David D’Arcy is a correspondent for The Art Newspaper

Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, until 7 January 2018