At first I thought it was just fake news: the former minister of antiquities for Egypt declaring last month that most ancient artefacts from his country across the world had been exported legally and should stay where they are. I cannot think of a more constructive statement for moving the antiquities debate forward because, finally, someone in a position of influence has acknowledged reality. Others may cavil at the intervention of Mamdouh el-Damaty, a renowned Egyptologist, professor at Ain Shams University and former director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, but it creates an opportunity to draw attention to what is really going on.

A new book highlights the official network of trade in antiquities that existed in Egypt during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, explaining El-Damaty’s view. The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930: the H.O. Lange Papers by Frederik Hagen and Kim Ryholt lists more than 250 licensed dealers active in Egypt from the 1880s until the trade was abolished in 1983. How many people know that even the Egyptian Museum had its own saleroom during the 20th century? As El-Damaty argues, gifts to foreign dignitaries, as well as the partage system, where discoveries were shared between the state and investigating archaeologists, explain how significant pieces left Egypt legally over the years.

Paperwork for legitimate artefacts can be limited or non-existent. For instance, I have a copy of an Egyptian export licence from 1970 that refers to “111 Egyptian antiquities packed in nine cases”, without pictures or individual descriptions—meaningless now but perfectly acceptable then. This has created masses of Egyptian “orphan works”, and these cause most disputes.

Today’s Egyptian government argues that artefacts without paperwork demonstrating clear legitimate provenance must be assumed stolen and returned to Egypt; guilty until proven innocent—a legally flawed position. Until recently, Egyptian embassies in Europe and the US approached dealers and auction houses with unfounded claims that they were offering stolen Egyptian property for sale. This approach leads nowhere.

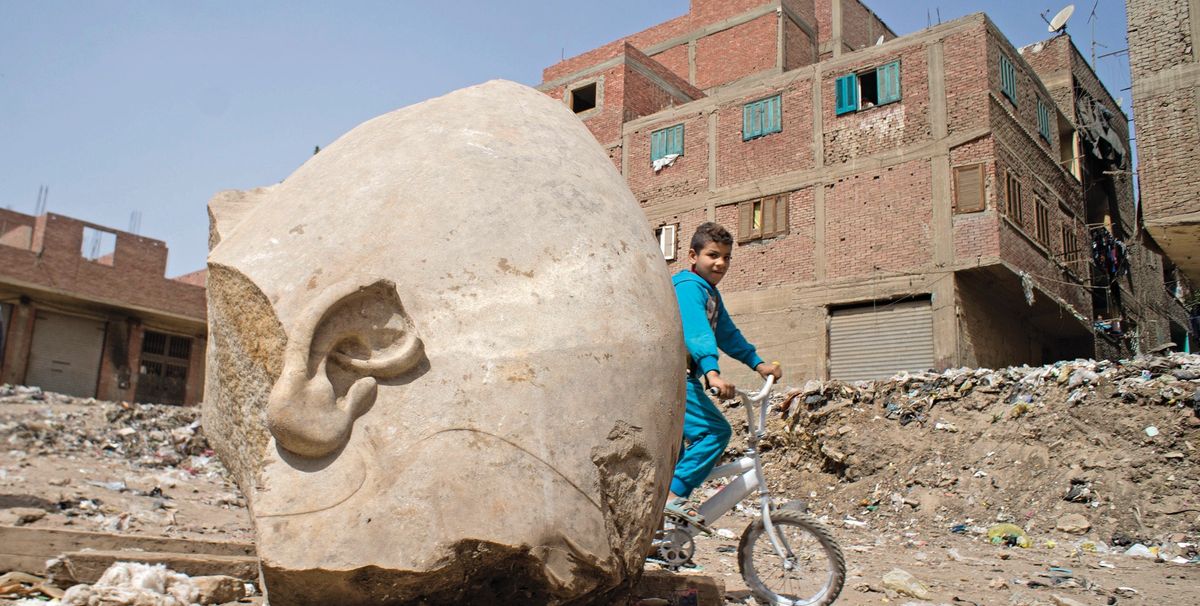

Antiquities have become far more newsworthy since the Syrian war. Egypt’s own crisis, following protests in early 2011, the so-called January Revolution, led to a collapse in tourism revenues, leaving the country’s archaeological sites at risk because government funding was no longer available to secure them.

The former minister of antiquities’ arguments propose a more constructive approach to help Egypt and countries like Italy, which are strapped for cash but face the heavy burden of preserving, conserving and storing vast quantities of minor objects. Lost labels and poor record-keeping, ironically, make these objects “orphans” too.

In 2015, a statement by Association of Art Museum Directors acknowledged the foolishness of this position and suggested that Italy open its borders to international sales of antiquities (with export licences) to raise revenues. Egypt could do the same.

It is also time the Italian authorities gave museums and the trade access to the Becchina and Medici archives, which list thousands of tainted (but not necessarily stolen) items. Anti-trade campaigners have used these archives for years to disrupt auctions and fairs by launching last-minute challenges over items in the catalogue. It’s time to play fair: grant the same access to museums and the trade and they could include the archives in their due diligence process, just as they do the Art Loss Register and Art Recovery.

Our concerted aim should be protecting cultural property in situ by guarding find spots and educating local people. It is context that counts more than the objects themselves. Artefacts removed illegally from their context lose their value for archaeology. The International Association of Dealers in Ancient Art (IADAA) has been campaigning vigorously to ensure appropriate policy is adopted. Our chief objective is to ensure that source countries meet their obligations formulated under Article 5 of the Unesco Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, thereby cutting off looting and illegal export at the source.

Looters cause nothing but trouble for legitimate antiquities specialists. The trade is only interested in working with legal objects that have been in circulation for decades or longer.

In 2009, Egypt’s then head of antiquities, Zahi Hawass, demanded the return of the Queen Nefertiti bust in the Neues Museum from Germany despite documents showing it had been acquired legally. El-Damaty’s rather different attitude may just be the beginning, but if it heralds a positive period of changing attitudes, it is significant indeed.

• Vincent Geerling is an Amsterdam-based antiquities dealer specialising in Greek, Etruscan, Roman and Egyptian artefacts. He campaigns widely for the legitimate trade, and addressed Unesco and Europol conferences among others in 2016